Sergey Vinogradov. Paupers near the church, 1899

Smolensk State Museum ReserveThe abolition of serfdom in Russia was a complex and multi-layered process that lasted decades – and wasn’t even properly finished as the Revolution of 1917 happened. Most Russians to this day don’t fully grasp serfdom and the consequences of its abolition. We make an effort to explain the blunt truth behind the shiny facade of Russian peasant freedom.

Portrait of Nicholas I of Russia

Sotheby'sFor a solid part of Russian history – starting from the mid-17th century, and until the abolition of serfdom in 1861 – peasants were tied to their land. They could also be bought and sold, their basic human rights weren’t respected. In the wake of the French Revolution, that proclaimed personal freedom as a basic human right, serfdom needed to be abolished.

Emperor Nicholas I organized at least ten secret committees discussing the abolition of serfdom – during his whole reign, from 1826, and until his death, in 1855. He understood that peasants must own their land above all, and pleaded with his son, Alexander II, not to deprive them of that, lest it lead to a national disaster. Nicholas said that serfdom was a “gunpowder magazine underneath the state.” He said the abolition was to become “the most necessary deed I am leaving for my son.”

The abolition of serfdom was also deemed so necessary because in the 1840s and 1850s, especially after the devastating Eastern War, peasant uprisings and revolts had increased in number. The fuse had already been lit.

Tsar Alexander II, Emperor of Russia (between 1870 and 1886)

Global Look PressAfter Nicholas I’s time, there were only 37 percent of serfs (about nine million) among Russian peasants. But the landlords were in a perpetual financial crisis. Two-thirds of their estates have been pledged to the state, and the nobles didn’t do business, so the landlords were desperately against the reform.

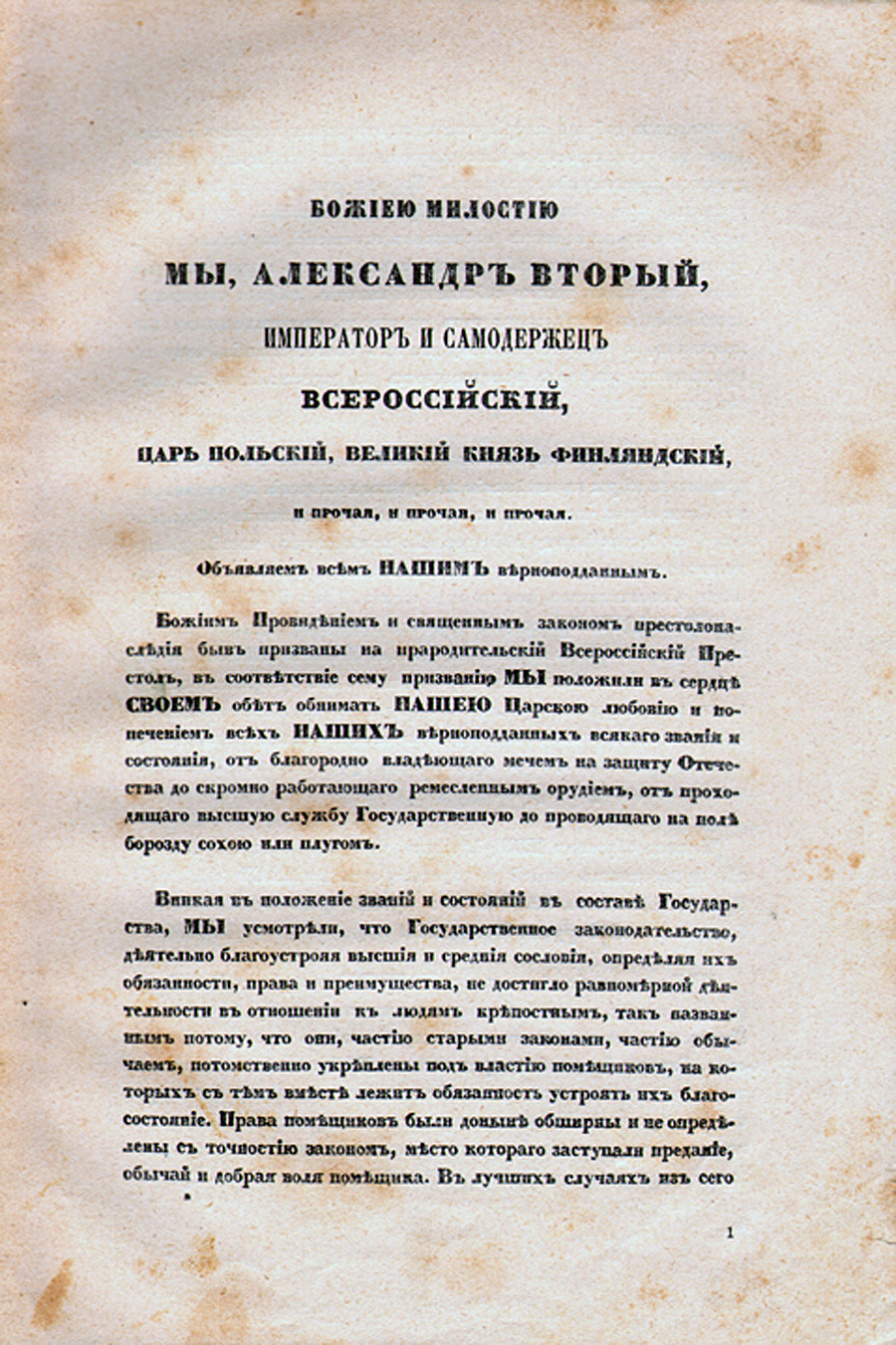

In 1857, a plan of the reform was drafted, but the landlords, members of the committee for the reform, opposed it strongly, and by 1859, the plan was amended in favor of the landlords. The peasants were given freedom without land – the worst scenario that Nicholas warned about. The Emancipation Manifesto was signed on February 19, 1861.

The first page of the Manifesto of February 19, 1861

Ivan SytinThe peasants gained personal freedom. For self-support, they gained small plots of land (about 3,5 hectares) that the state bought from the landlords. These small plots, however, were loaned to the peasants by the state on a 5,6 percent annual interest. They couldn’t leave or sell these lands for another 49 years!

The landlords took the best lands, leaving their peasants with infertile or swampy plots. Freedom for peasants was only in their newly installed communal self-governance. In all other respects, their lives remained unchanged.

The landlords were pushed, too. The state paid them for their former serfs in bonds (stock papers) that could be cashed, but cost much less than their nominal value. The state should have paid the landlords 902 million rubles (for about nine million serfs), but 316 million were retained by the state for the landlord’s debts. To put things into perspective, Russia’s annual budget at the time was 311 million rubles.

Russian writer Ivan Turgenev in Baden-Baden

K.WertzingerWas this sum enough? Well, a landlord with an estate with 300 serfs was considered wealthy in those times; but after the reform, a landlord who owned 300 would get only 30 000 rubles – this could support a nobleman’s family’s lavish lifestyle for only about five or six years. The money needed to be invested or put on a bank account. But the noblemen didn’t know how to use the money. Historian Semyon Ekshtut writes: “The nobility… considered this sum as compensation for their loss, not as a startup capital… The nobility didn’t invest their money in the development of the country but preferred to squander it abroad.”

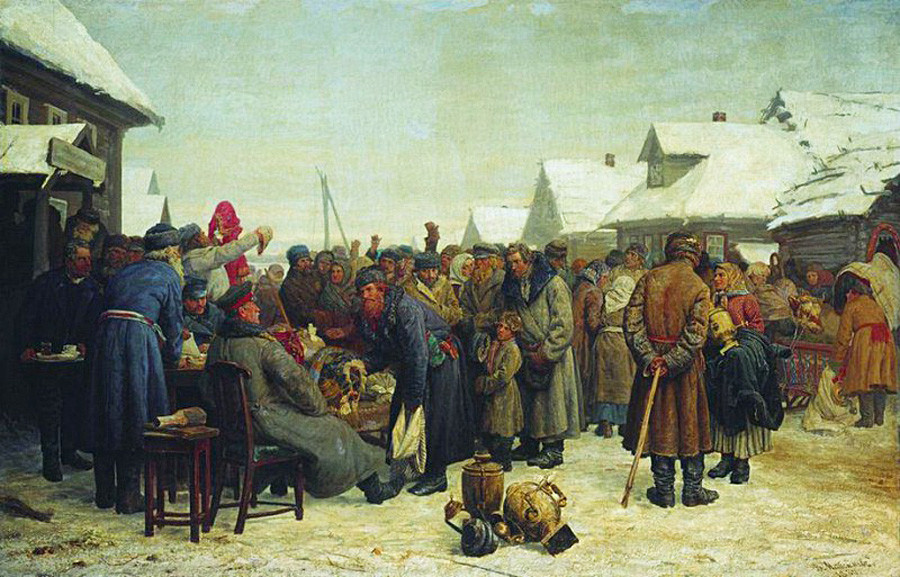

An auction for arrears, by Vassily Maximov, 1880-1881

Berdyansk Art MuseumSoviet history textbooks said serfdom should have been abolished because it hindered economic growth, as free peasants would work better. Unfortunately, this isn’t true. Alexander Malakhov argues that an average American slave worked 2,6 times as much as a Russian serf.

Serfs were ‘motivated’ to work by their landlords using corporal punishment and fees, but the state serfs, who were personally free and paid taxes to the state, worked worse and less than the private serfs: state serfs have sown 42 percent fewer seeds, and exhibited 16 percent less productivity. So, after the alleviation of taxes and workdays that the reform brought, the peasants started working less, not more; and even if there were some wealthy and successful people among them, who managed to open their own businesses, they were still a minority.

"Reading of the 1861 Manifesto" by Grigoriy Myasoyedov, 1873

Tretyakov GalleryImmediately after the Manifesto, a great lot of peasant riots started. The peasants considered the reform to be “fake,” as it left them in the same state they were in – working for the landlord. Many peasants revolted by stopping working. In March 1861, army regiments were sent to nine (out of 65) Russian governorates (regions) to stop the riots. In April, 29 governorates were rioting, in May – 38. In total, in 1861, 1176 riots happened. By 1863, they numbered over 2000, with over 700 of them suppressed by the army. This wasn't a peasant war – but what was appalling is that the peasants actually paid more than the land cost.

In 1855, the total cost of peasant lands amounted to 544 million, but the peasants were to pay 844 million for them (taking into account the yearly 5,6 percent increase), and the cost only grew with time: by 1906, the peasants had paid 1,57 billion rubles for these lands (triple the cost!). The peasants were pauperized and started seeking income in towns, where they were deprived of their families, native lands, angered and ready to riot against the corrupt state that robbed them.

Sergey Vinogradov. Paupers near the church, 1899

Smolensk State Museum ReserveAlmost all noble families of Russia were broke by the start of the 20th century. Even in ‘The Cherry Orchard,’ a play by Anton Chekhov, Firs, a manservant, considers the emancipation of the Russian serfs “a disaster” for the peasants and their landlords alike.

The nobility lost all their money and didn’t know how to work or do business, so they were no use for the state. And the former peasants had now turned into the working class, broke, angry, and living far from their homes and families (if they had any) – fertile soil for Communist propaganda.

It’s no wonder that the first decree of the Soviets was about land. Lenin promised to return the land to the peasants – and even if he actually didn’t do it in the end, that’s what helped Communists to ignite and win the Revolution – the selfish desire of the Emperor and the nobility to separate themselves from the general population and not do anything at all.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox