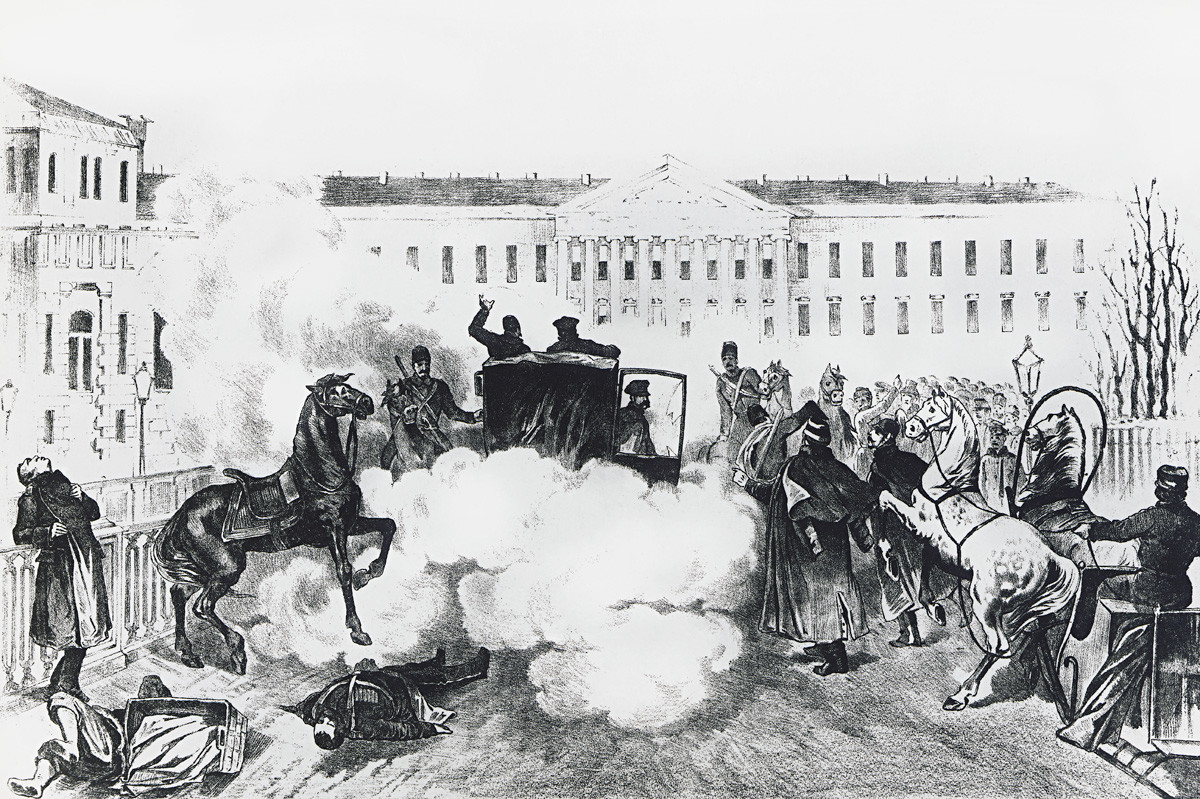

When terrorists from the ‘Narodnaya Volya’ (National Will) group planned the assassination of Alexander II, they counted on the death of the oppressor-tsar to inspire a national upheaval of such proportions that the entire country would unite in revolt. But instead, they accomplished just the opposite: even the liberals mourned the tsar, while Narodnaya Volya - instead of being hailed as liberators - were declared absolute monsters. It could not have been any different. In the eyes of most Russian people, the Russian tsar couldn’t commit any sin or wrongdoing, because he was God’s emissary on Earth.

The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in St. Petersburg, Russia, 19th century.

Getty ImagesNow, over 100 years have passed since the last Russian monarch abdicated the throne. But the collective Russian memory of a ruler as someone whose power draws its source not from the law or popular will - but from God himself - lives on. Which is why the Russians were used to blaming anyone but the tsar for their woes - from the boyars to the ministers.

But what was the actual relationship between the Tsar and God?

"Emperor Nicholas II of Russia," by Boris Kustodiev, 1915.

Russian MuseumEvery civilization throughout human history has had its own take on the relationship between God/gods and rulers. In Ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was considered the earthly embodiment of the god Horus. In Ancient China - which did not have a monotheistic religion, the emperor was proclaimed as the ‘son of heaven,’ his authority being perceived with humility as if it were destiny. In the Roman Empire, the emperor would perform sacrifices on behalf of his people, asking gods for mercy, fortune, a good harvest and so on; in this respect, the ruler took on the role of his people’s foremost priest.

The Christian framework was different. In Romans 13:1, we encounter the following: “Let every soul be subject to the authorities being above him. For there is no authority except by God; but those existing are having been instituted by God,”; and then, in Proverbs 8:15: “By me kings reign, and rulers enact just laws.”

With the advent of Christianity, the ideology had changed. Theologist Elena Khaupa writes that for God-fearing Christians, the meaning of authority was that it helped them prepare for eternal life: “The emperor was accountable to his people for their salvation in the eyes of God.” This Byzantian conception of an emperor’s authority was borrowed and implemented by the Rus.

'The coronation of Alexander II in the Dormition Cathedral in Moscow,' by M. Zichi.

Russian MuseumWhat were the key ways in which the spiritual authority of a Byzantian ruler – same for the Russian Tsar – was different from that of the Roman Pope?

The Catholic Church claims that the Pope is the successor to the apostle Peter – the first apostle of Christ. “Take care of my sheep,” Christ said unto Peter (John 21:15).

The Russian Orthodox Church contests that view, being of the opinion that the Pope does not rule over the Church of Jesus Christ on this Earth, and only deserves a sort of special status far from absolute authority.

According to the Orthodox theologians, ‘The Anointed One’ - or the Messiah, was a status that could only have been bestowed on one person, and that was Jesus (the name itself descending from the Greek word for “the anointed one”). The secular ruler, however, carries the role of God’s emissary – an important difference. In this role, the emperor (or Tsar) is both imbued with absolute power, but also absolute responsibility to God. So, what do we have as a result? The tsar must obey God’s laws, but the earthly ones he can simply write himself. Pretty neat!

Part of that responsibility to God meant steering the country out of crisis whenever its faith was in peril - such as presiding over religious matters and organizing meetings, as well as acting as a judge in any quarrels and rows between the church hierarchs. For this reason, Ivan the Terrible, having ascended to power in 1551, immediately set about organizing the so-called Council of a Hundred Chapters, intended to put an end to a whole number of ongoing arguments and calm the in-fighting in the Russian Church.

With absolute power, however, also came absolute responsibility, and the ruler knew well that his life was to be devoted to this duty. The Russian coronation ceremony was the visual proclamation of this pledge. “Coronation” is a Western word, but in Russian, the process is actually called “chrismation (anointment) to tsardom,” or “being wed to the tsardom”, a very important difference - one that is lost in translation when speaking of Russia.

Anointing the Tsar was a symbol of this ‘wedding’ to the tsardom and its people. As all weddings are made in heaven, so is the tsar wed to his tsardom, and cannot abscond from this holiest of unions. That is why, following Nicholas II’s abdication, many Russians simply refused to believe that the tsar could have abdicated at all – such a move was deemed unfathomable.

The Holy Synod in 1911

Archive photoAnother aspect to note is, of course, that the Tsar - who was greater than the Church - had the final word over the latter’s bid for either its own authority on certain matters, or its ownership of property. Any encroachment by the tsar on what the Church was doing was, therefore, not deemed illegal. That is how Peter the Great subsequently got away with abolishing the Patriarchate and instituting the Holy Synod in 1721. Who was going to stop him? Constantinople gave the blessing. The Russian Tsar was, in practical terms, the head of the Orthodox Church, and his word trumped that of the Patriarchate. The Pope, on the other hand, was different: no king would ever be able to overrule him on holy matters.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox