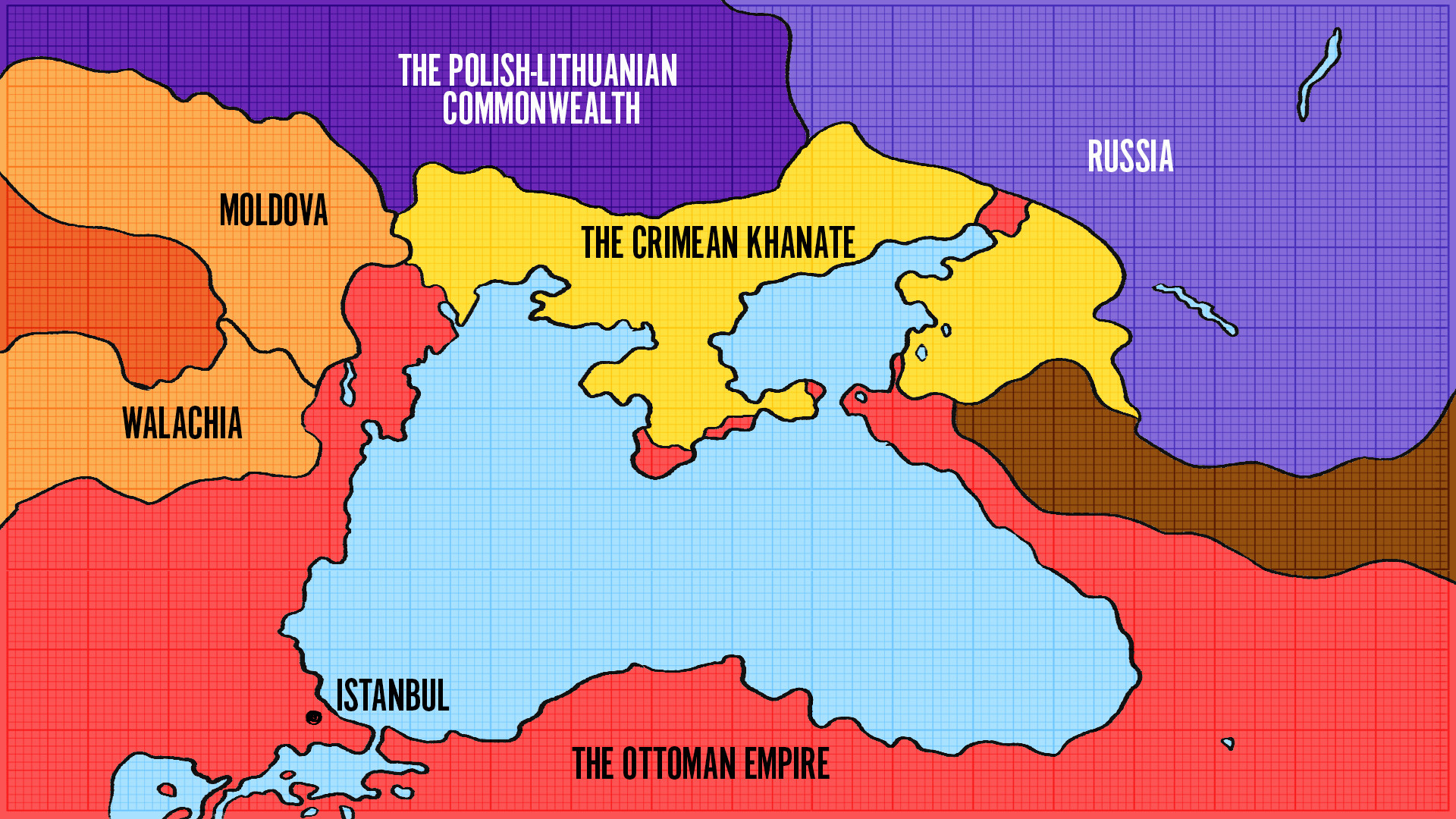

The Crimean Khanate was once a part of the Golden Horde. After the Golden Horde fell apart because of dynastic conflict, the Crimean Khanate was established in 1441.

In 1475, some important seaports of Crimea became part of the Ottoman Empire (created by Turkish tribes), while the Crimean Khanate as a whole became the Ottoman Empire’s satellite state. Hence, the Black Sea became surrounded by Ottoman and Ottoman-dependent territories.

From South, Crimea was surrounded by the Ottoman Empire's lands

Irina BaranovaIn the 16th century, Russia (Moscow Tsardom at the time) began expanding its territories after the Golden Horde collapsed. And after conquering the Kazan Khanate and the Astrakhan Khanate, Russia proceeded further south. Meanwhile, the Crimean Khanate’s Tatar nomads were pillaging the outskirts of Russia’s lands, which troubled the trade and agriculture of the Russian South greatly. By the beginning of the 18th century, it became apparent that for further development, Russia needed access to the Black Sea.

Portrait of Russian statesman Prince G. A. Potyomkin-Tavrichesky

HermitageIn 1736-1737, the Russian army invaded Crimea and went through it. But the Russians couldn’t maintain supply lines, because the Russian territories were too far away, separated from Crimea by the vast territory of the Wild Fields – roughly, the Pontic steppe of Ukraine, north of the Black Sea and the Azov Sea, as well as South and East Ukraine.

The possibility to effectively supply military forces in Crimea appeared only in the 1760s and 1770s, after a new imperial province, the Novorossiya (New Russia) Governorate was created in 1764. With supplies starting to arrive from the new governorate, the possibility of an advance towards Crimea became real. This was done under the control and supervision of Prince Grigoriy Potemkin, Catherine the Great’s closest friend and military counselor.

Vasily Michailovich Dolgorukov-Krymsky (1722-1782) by Alexander Roslin

Tretyakov GalleryDuring the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774, Crimea was probably Russia’s main goal. By 1771, Crimean Tatars refused to fight for Turkey, and the Ottoman leaders didn’t have enough military force to protect Crimea. So in the summer of 1771, the Russian army, led by General Vasily Dolgorukov, took Crimea in just 16 days. Khan Selim III Giray, a Turkish stooge, fled to Constantinople.

In 1772, a new pro-Russian Crimean Khan, Sahib II Giray, declared his khanate a free state under Russia’s protectorate. However, the Ottoman Empire didn’t wish to acknowledge this, and the war went on.

Şahin Giray (1745—1787), the last Khan of the Crimean Khanate

Public domainIn 1774, the Ottoman Empire had to sign the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca. According to it, the Crimean Khanate formally gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire and Russian Empire; Russia, however, gained Kerch (an important military and trade port). But the Turkish sultan had preserved the religious power – the Crimean khans still had to be approved by the sultan.

Turkish forces didn’t leave Crimea, hoping that eventually, the sultan would manage to get the peninsula back into the Ottoman Empire’s hands. In 1776, the Russian army entered Crimea and appointed another khan, Şahin Giray, who agreed to have the Russian army deployed at the peninsula. Şahin Giray tried to start European-type reforms.

But then the Crimean people started to riot. The Muslim part of the population against the Christian one and against the Russia-biased khan. In 1778, Russia had to send military hero Alexander Suvorov to suppress the riots.

Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov of Rymnik, Prince of Italy (1729–1800)

Vladimir Boiko/Global Look PressFollowing orders from Grigoriy Potemkin, Alexander Suvorov supervised the resettlement of a Christian part of the Crimean population to mainland Russia, in the northern Black Sea coastal area (since 1764, these lands were part of Novorossiya). In total, over 30,000 Armenians, Greeks, and Georgians were relocated from Crimea.

Suvorov prevented the Turkish army from further deploying in Crimea, and by 1779, most of the Russian army had gone, too – Alexander Suvorov was posted to Novorossiya. However, Turkish spies continued to provoke unrest in Crimea, with khan Şahin Giray suppressing any riots with remarkable cruelty.

By 1782, Grigoriy Potemkin addressed Catherine the Great with a memorandum that suggested joining Crimea to Russia, in order to “block the way for the Turks” and secure the Empire’s presence in the Black Sea. The empress agreed and issued a formal proclamation of annexation on 19 April 1783. On his way to Crimea with the document, Potemkin suddenly learned that Şahin Giray had stepped down from his throne – the Crimean Tatar nobility had openly opposed him and preferred Russian power to control them formally.

Aq Qaya (White Rock), a mountain in Crimea where Grigoriy Potemkin accepted the Crimean people's oath of allegiance to the Russian crown in 1783,

Angu (CC BY-SA 3.0)On July 9th, 1783, Potemkin solemnly declared Catherine’s proclamation at the flat top of the Aq Qaya mountain. After that, representatives of the Crimean nobility and common folk formally swore their allegiance to Catherine the Great as the Russian sovereign. Only at the beginning of 1784, the Ottoman Empire reluctantly accepted the new status of Crimea as a Russian province.

After the news of the annexation spread internationally, only France filed a note of protest, but the Russian diplomats responded, saying Russia didn’t object to the annexation of Corsica and was expecting the same from France concerning Crimea; also, Catherine reminded them that the annexation was performed only to calm the heated situation at the Russian-Ottoman border.

In 1784, Sevastopol, the new Crimean capital, was founded by Potemkin, and the Crimean governorate was established. The population of Crimea had been significantly diminished – a great part of the Muslim population fled to Turkey. Potemkin insisted that the Russian garrison treat the local Tatar population with respect. Tatar noble families had been installed as Russian nobility, gaining access to many privileges, except the right to possess Christian serfs.

Onward from 1780, and with considerable help from Prince Grigoriy Potemkin, who considered Crimea to be a kind of ‘his’ land, since he had conquered it, unprecedented agricultural and economic development began in Crimea, with its population slowly being restored and added to by settlers from mainland Russia.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox