Today all the world’s military powers agreed that military aviation is a crucial force. Some wars are won exclusively with air raids, without the use of a single foot soldier. However, in the first half of the 20th century, not many of them got the point.

Despite the fact that WWI had demonstrated the high potential of aviation, many countries still saw it as a secondary force, intended only to provide support for land troops and navies. The U.S., where it was not even a separate branch, but an arm of the Army, so to speak, shared such beliefs.

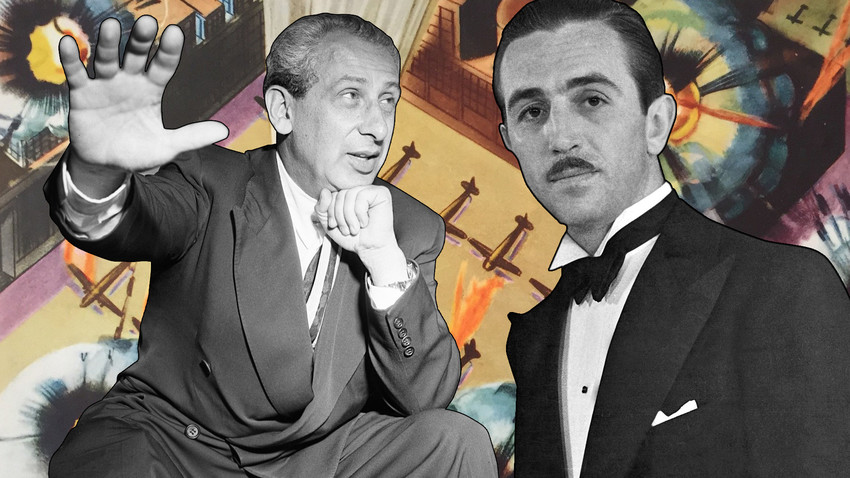

Many air power supporters called for a change to this situation and to give aviation more credit. The famous American animator Walt Disney let one of them - the former Russian pilot Alexander P. de Seversky - be heard by millions.

Alexander P. de Seversky standing by his plane in 1933.

Getty ImagesSeversky knew aviation firsthand. A military engineer and combat pilot, he conducted 57 missions in WWI and was considered one of the best pilots in Russia. When the Bolshevik Revolution forced him to move to the U.S., he proved himself there as a prominent aviation theoretician and inventor. Among his inventions were the world’s most accurate bombsight and America's first modern fighter aircraft P-35.

As an air power advocate, however, Alexander Seversky reached much more publicity. His most important idea was that air power was an inherently strategic weapon. Long-range bombers fly over enemy armies and navies and, by destroying the enemy’s capital, government, industry and most vital areas, strike him in the very heart.

These advantages of strategic aviation seem obvious today, but in the 1920-30s by no means all political and military leaders were ready to finance and resource the development of dubious long-range aviation projects, preferring the old tactic of using frontline bombers.

Seversky criticised such approach, since in his view, military aviation should not squander its unique capability on tactical support for troops on the battlefield, but concentrate on strategic missions. If air power did its job properly, occupying enemy territory would become an outdated concept and cease to be an objective of war.

A new amphibian plane, designed and constructed by Alexander Seversky, 1933.

Getty ImagesStrategic bombers alone could bring the enemy to its knees: “Having knocked the weapons out of his hands and reduced the enemy to impotence, we can starve and beat him into submission by air power,” he declared.

Especially hard was Alexander de Seversky’s criticism of the Navy. Sea power, according to him, was obsolete and surface ships were doomed in the face of the emerging air dominance.

In his articles he fiercely protested against the creation of a large expensive fleet: “Our great two-ocean, multi-billion-dollar Navy, now in construction, should be completed five or six years from now - just in time to have all of its battleships scrapped.”

The sum for one battleship could better be spent on building hundreds of long-range bombers. Each bomber could theoretically destroy or put out of commission an enemy’s capital ship. Such bombers could simply ignore and fly over an adversary’s ships to pulverize the foe’s homeland into submission.

Seversky supposed that as the aircraft range expanded, ocean areas open to naval activity would diminish until they disappeared entirely. “No land or sea operations are possible where control of the air is in the hands of the adversary,” he used to say.

Alexander Prokofiev de Seversky with a model of a twin-fuselage aircraft, circa 1935.

Getty ImagesThe fact that the U.S. possessed half a dozen aircraft carriers and their sea-based fighters would protect the naval fleets against enemy planes was met by Seversky with the counterargument that land planes were far superior to carrier-based ones.

The fact that the Air Force was under the Army’s control was heavily criticized by the Russian pilot. While the General Headquarters Air Force functioned as the operational or combat arm, the U.S. Army controlled the crucial support elements of its training, finances, and procurement.

Seversky sincerely believed that the Air Force would not overcome its “organizational nightmare” and could not develop properly until it became a separate branch with a single command. He was sure that its present commanders were ground soldiers first and airmen last.

Such a situation led to the U.S. Air Force in the 1930s being among the last on the list in terms of importance and financing. Only by miracle did it save the B-17 Flying Fortress project, which soon became vital.

Alexander de Seversky in the cockpit of the British de Havilland Vampire jet fighter, England, 1944.

Getty ImagesAlexander Seversky believed that having an independent Air Force command with a separate budget would give a green light to such important and promising projects as the Douglas XB-19 bomber. “If we allow,” de Seversky said, “the outworn, terrestrial-minded thinking of the Army and Navy to dominate, we shall find ourselves fatally handicapped - losers in the race for air supremacy, which we ought to win.”

Many Army and Navy commanders hated Seversky and called him a madman. However, early events in WWII proved many of his ideas to be right. The battles of Norway (1940), Dunkirk (1940), Britain (1940), and Crete (1941) demonstrated that military aviation now played a crucial role in modern conflicts.

Then on Dec. 7, 1941, U.S. society was left reeling when Japanese aviation sank four battleships and two destroyers and seriously damaged nine other naval vessels, including three cruisers and three battleships during an attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbour. This clearly demonstrated the vulnerability of warships in the face of a coordinated and near-unchallenged air attack.

Further articles by Seversky received high attention from the public. His analyses of aerial warfare, as well as his forecasts of tactical, strategic, and technical developments, won him a reputation for credibility.

Especially popular was his Victory through Air Power, released in April 1942. Soon after Alexander got an unexpected call from a person who made the whole world listen to the former Russian pilot.

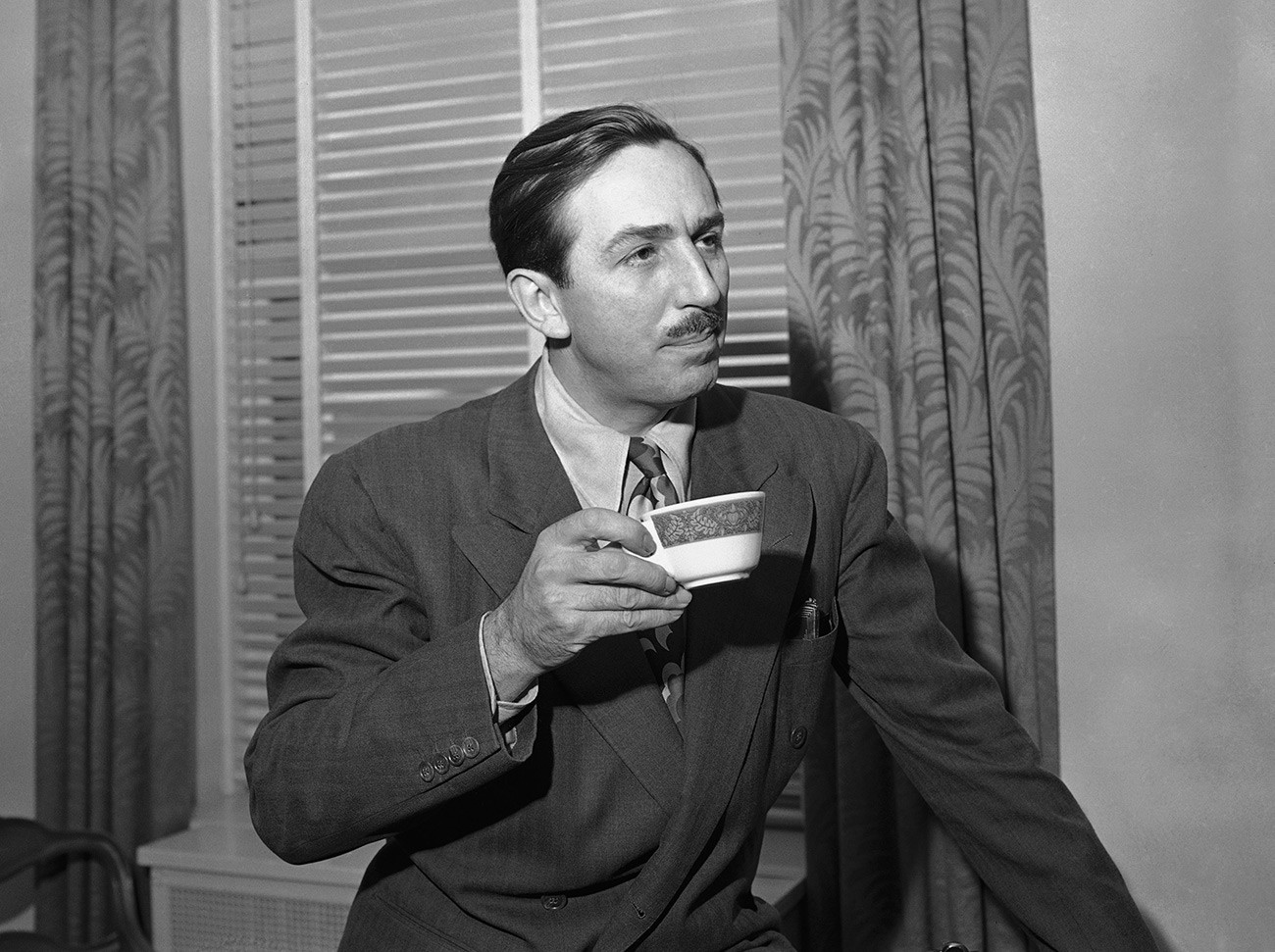

Walt Disney in 1941.

APWalt Disney called Seversky to say he was “overwhelmed by the logic of the book.” “He had read my book and since it dealt with the future, he wanted to animate the events yet to come which would lead to victory (in the war),” Alexander recalled.

A contract was signed and work commenced on an animated movie version of Victory through Air Power, in which animation, telling the history of aviation and demonstrating the need for its further development, was alternated with live-action segments. In them, Seversky himself stressed the importance of the United States controlling the skies, exercising air power offensively, and forming a single command over America’s military air forces.

“We worked,” Alexander remembered, “in his studio at Burbank, in my bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel, sometimes in restaurants, sometimes while driving to and from the studio.” Disney even hired an elocutionist to straighten out Seversky’s pronunciation and fix his strong Russian accent.

Seen by millions, the movie went viral. Churchill and Roosevelt saw the film twice and then had it shown a third time for the benefit of the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Roosevelt was impressed by Seversky’s comments and excited by Disney’s animations, which demonstrated naval vessels being blown apart by aircraft.

As the Russian pilot’s biographer James K. Libbey wrote in his book Alexander P. de Seversky and the Quest for Air Power, it was this movie that convinced the Allied leaders that the final date for what became known as Operation Overlord would be determined by the availability of sufficient air power to protect the ships and their precious cargo of soldiers and materials as they crossed the English Channel.

As a result, 8,000 aircraft served as a virtually impenetrable shield over the Normandy invasion. Over 5,000 more aircraft were ready to engage at any moment. The Luftwaffe forces were completely suppressed.

Alexander de Seversky did not originate the ideas of global air power, its dominance over surface forces, or massive retaliation, but, to a very great extent, he explained and sold them to the public.

Col Phillip S. Meilinger, in The Paths of Heaven. The Evolution of Airpower Theory, claimed that Alexander P. de Seversky was one of the best known and most popular aviation figures in the U.S. during WWII. His passion was air power, and his mission was to convince the American people that it had revolutionized warfare, becoming its paramount and decisive factor.

And not only in America. After the war Alexander Seversky, as a special consultant to the War Department, visited Japan and talked to Emperor Hirohito. The latter told him that he had watched the movie and was deeply troubled by its predictions concerning the fate of his country at the hands of U.S. air power.

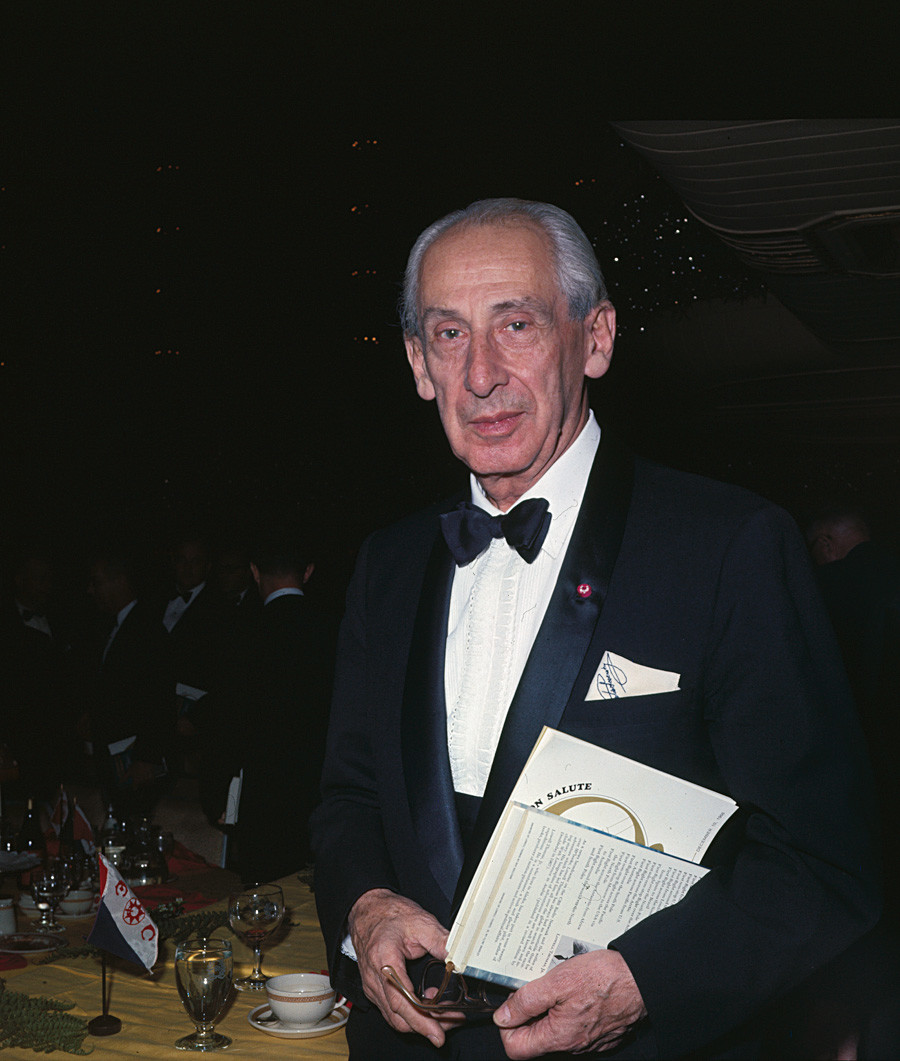

Alexander de Seversky at an Explorer's Club dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria, 1968.

Getty ImagesAs Seversky had dreamed, American military aviation became a fearsome force during WWII. In 1947, the USAF was finally established as a separate branch of the U.S. Armed Forces. Soon after it became the largest and strongest air force in the world.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox