All of a sudden, Russia's flagman ship in the Black Sea blew up.

Anton RomanovOn October 2, 1916, most people living in Sevastopol (a coastal city in Crimea, about 1,800 km south of Moscow) woke when a loud explosion came from the harbor. A tremendous fire started as black smoke rose from the Imperatritsa Mariya, the flagman battleship of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, which was anchored in the harbor.

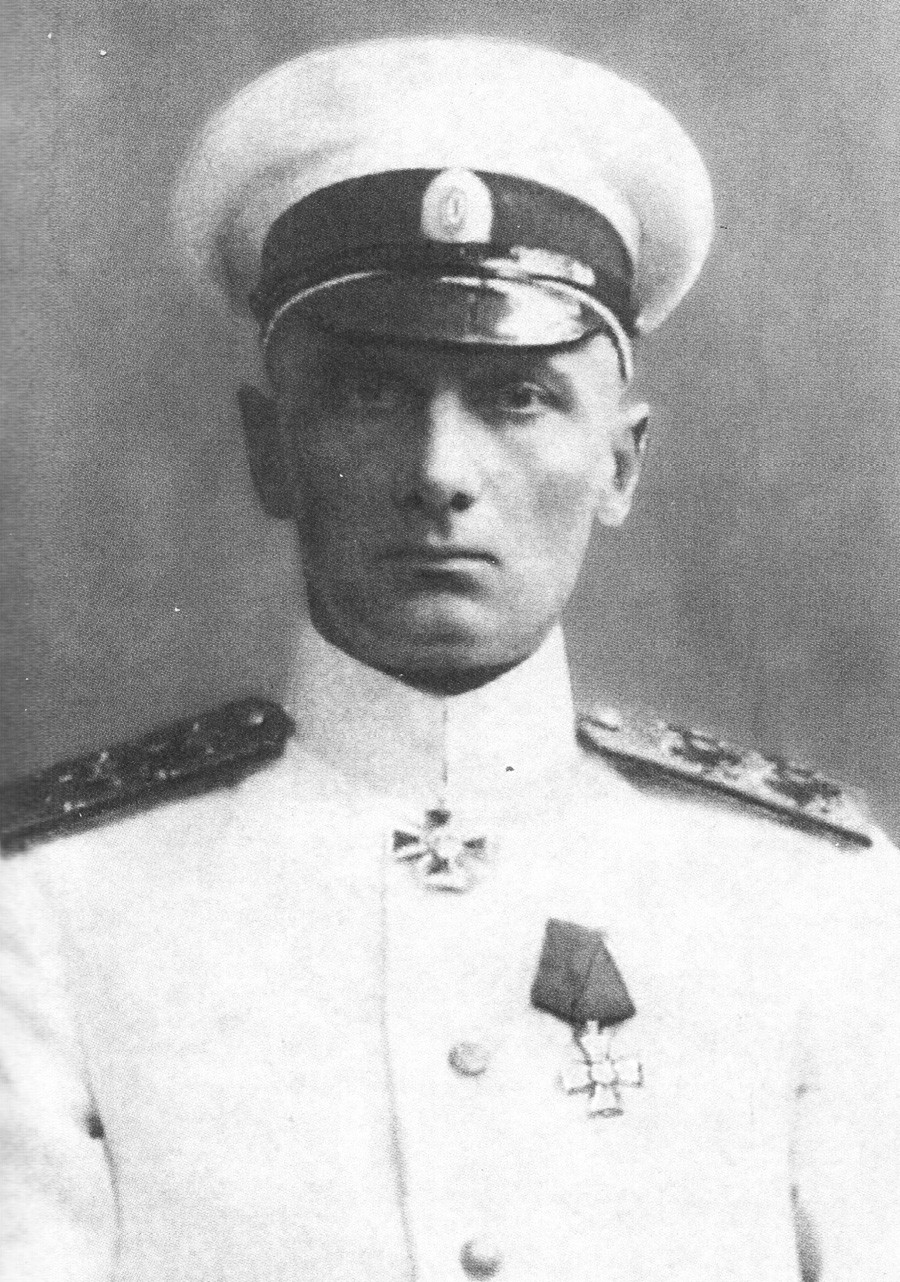

“I testify that the crew did everything possible to save the ship,” Admiral Alexander Kolchak, who led the Black Sea Fleet, would later write in a report. True: hundreds of sailors rushed to put out the fire, but in vain. A series of 25 more explosions followed as the fire reached powder magazines, and 320 of the ship’s 1220-people crew were killed. Imperatritsa Mariya, damaged beyond repair, sank.

That was a serious blow to Russia’s fleet, especially in 1916, when the empire was fighting in World War I and opposing Turkey for control of the Black Sea. Why was Imperatritsa Mariya so important, and what caused the explosion?

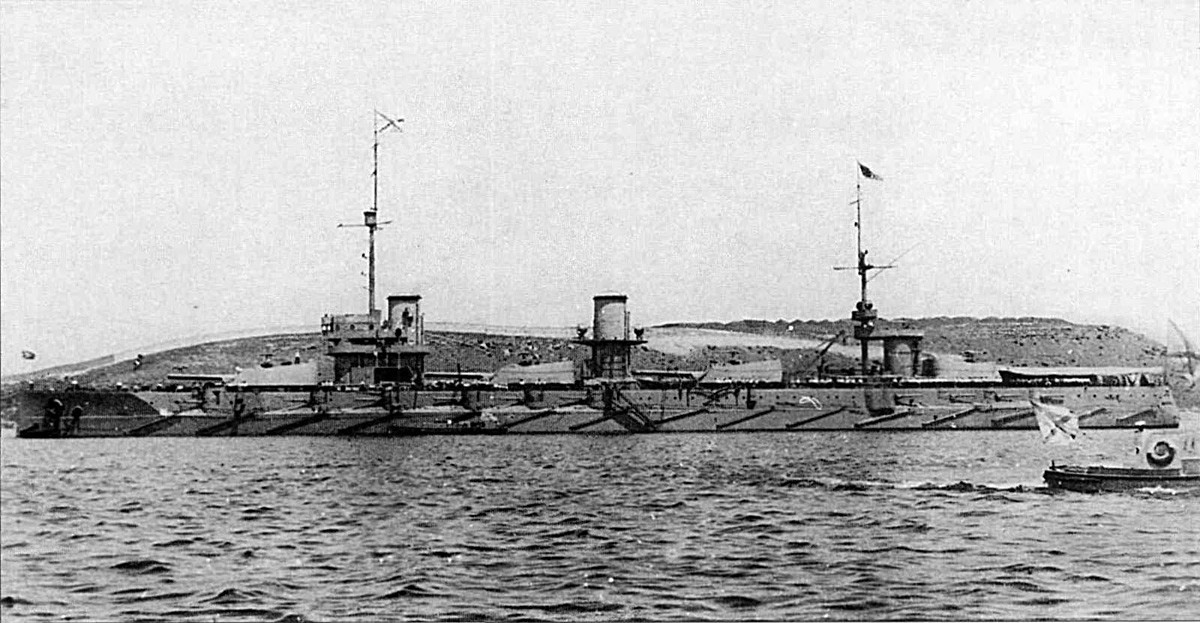

Imperatritsa Maria before the incident.

Archive photoThe first question is easy. As a brand-new battleship launched in 1913, Imperatritsa Mariya (“Empress Maria” in Russian, named after Nicholas II’s mother) belonged to the elite ships of the Imperial Navy, the heavy dreadnoughts. Originally, that class of ship was designed in Britain, and Russia started building them after its humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905.

Dreadnoughts were all the rage back then. With agile maneuvering abilities, and equipped with heavy and long-range artillery (each carried twelve 305-mm naval guns and twenty 130-mm guns), they completely outclassed the German-made cruisers that the Ottoman empire used. By the start of World War I, Russia had three dreadnoughts in service on the Black Sea, which let it establish naval dominance in the region.

The Imperatritsa Mariya was the pearl of Russia’s navy. Admiral Kolchak, commander of the Black Sea Fleet, made it the flagman ship.

Alexander Kolchak, 1916.

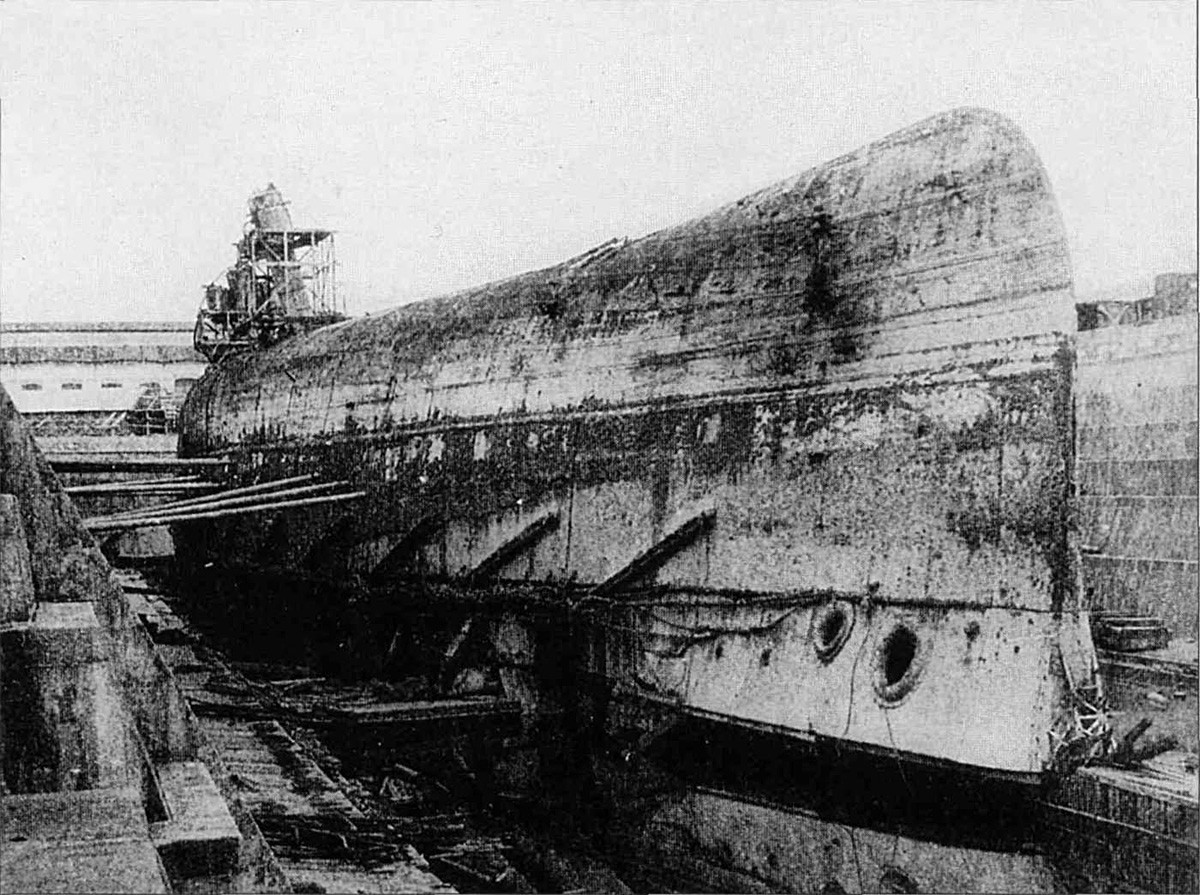

Archive photoLoss of the fleet’s finest warship and 320 lives without a shot being fired, and in one’s own harbor, was not only harmful but also a horrible humiliation. The naval command immediately started an investigation led by three high-ranking officers, including naval engineer Alexey Krylov, who had designed the dreadnoughts for Russia. There were three major hypotheses as to why the Mariya exploded: 1) spontaneous combustion of gunpowder; 2) combustion caused by human error; or 3) someone’s malicious intent.

After a thorough examination of the tragedy, consisting mainly of interviews with witnesses (forensic expertise was hard to conduct since the dreadnought was lying on the seabed), the commission came to a conclusion that can only be described as vague: “There is no possibility of coming to a precise and evidential conclusion, we have to evaluate the chance of those (three above-mentioned) assumptions based on the circumstances revealed throughout investigation.”

To make a long story short, malicious intent was more or less ruled out as a credible reason for the explosion. Kolchak later reported: “I believed there was no malice. During the war such accidents occurred more than once in other countries: Italy, Germany and England…”

A controversial version appeared rather suddenly, almost twenty years later, years after Admiral Kolchak had been shot by the Bolsheviks and Joseph Stalin ruled the country. In 1933, Viktor Wehrmann, a citizen of German origin was arrested and tried in Mykolaiv (now Ukraine), testifying that he spied for the German empire during World War I, and that he had taken an exceptional interest in the Mariya and other major battleships. At least that’s what Nezavisimoye Voyennoye Obozreniye (NVO) wrote in 1999, with reference to research conducted in the archives of the FSB (Federal Security Service).

“Since 1908, I was personally involved in espionage work in the following cities: ...Sevastopol, where engineer Wieser led the intelligence work,” NVO quotes Wehrmann’s testimony. “Wieser has his own spy network in Sevastopol.”

At the same time, according to the NVO, in 1916 Wehrmann was deported to Germany and is unlikely to have had the chance to organize a theoretical sabotage attack. However, he could have trained and organized other agents to possibly conduct such sabotage. Nevertheless, there is still no solid evidence that this in fact happened, and it doesn’t seem that any conclusive proof will appear anytime soon.

In the chaos of war and revolution that hit Russia a year later, the sinking of the Mariya was quickly overshadowed by larger events. The Dirk by Soviet writer Anatoly Rybakov, is a story that depicted the events connected to the explosion, and the author wrote: “Many tried to investigate the case but with no conclusive result… and then the revolution came.”

So many things were destroyed in the upheavals that overwhelmed the country from 1917 to 1922 that the loss of a warship, even a major one, became just another grain of sand on the windswept ‘beach’ of Russian history.

This article is part of the

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox