Soviet Jews leaving for Israel. Facing hidden anti-Semitism at home, they decided to find a new one.

Legion Media; Moshe Milner/National Photo Collection of Israel“Anti-Semitism, as an extreme form of racial chauvinism, is the most dangerous vestige of cannibalism,” Joseph Stalin said in 1931, answering an inquiry of the U.S.-based Jewish News Agency. Thus he emphasized that the USSR has nothing against Jews and, as an internationalist state, had nothing to do with anti-Semitism. The reality, though, was quite the opposite.

It was Stalin who wiped prominent Bolshevik leaders of Jewish origins (Leon Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and so on) from the Soviet political arena. It was he who, after World War II, launched a full-scale campaign against Jews in Soviet culture, science and public life. Officially, they were nicknamed “rootless cosmopolitans” but everyone understood who those cosmopolitans were. “In order not to be called an anti-Semite, call a Jew a cosmopolitan,” a popular saying went back then.

(Here you can read in detail about Stalin’s attacks on Soviet Jews.)

When Stalin died in 1953, it was a big relief for Jews: the state dismantled its anti-Jewish campaign. But still, Jews remained one of the least loved children of the Motherland.

Israel's embassy employees at the Moscow synagogue in 1964. Three years later the USSR would close the embassy and force them to leave.

SputnikUnfortunately, Russia had a long history of anti-Semitism: in the Russian empire during the late 19th to early 20th century, the poorly-educated masses believed in Jewish animosity towards Christians and absurd rumors of them drinking the blood of Orthodox babies (see the infamous Beilis trial). By the 1950s, this libel was more or less refuted but the perception of Jews as a cunning people enjoying great influence all over the world remained.

The declaration of independence by Israel in 1948 only worsened the state of things for Soviet Jews: from then on, the Kremlin looked at them with suspicion, bearing in mind they may have had Israeli, not Soviet interests in mind.

“Being a Jew was a bit shameful when I was young, this word was all but prohibited” Lev Simkin, a writer and publicist who grew up in the USSR in the 1960s and 1970s,explains. “On the other hand, they (the authorities) criticized Zionists, not Jews… The majority didn’t even know that Zionism is nothing more than the idea of creating a Jewish state… But the people quickly got that ‘Zionists’ means ‘Jews’.”

Filming from the anti-Zionist (or straight anti-Semite) Soviet movie of 1973, never aired.

The tricky thing about Soviet anti-Semitism after Stalin is that it was hidden, not promoted at the official level, reduced to domestic rudeness and criticism of Israel in the press: as Moscow strongly supported the Arab states in their permanent conflict with Israel, the Jewish state was a natural enemy.

The authorities were doing their best to save face and not cross certain lines, being anti-Zionist – but not anti-Semite. For instance, they didn’t play the 1973 film Secret and Explicit (The Aims and Acts of Zionists), which used materials from Nazi propaganda movies portraying the alleged global Jewish plot. Leonid Brezhnev decided that it was too much after receiving a letter from a cameraman of Jewish origin, loyal communist Leonid Kogan, that said: “It’s a gift for those who slander our Soviet nation… the film is riddled with an ideology alien to us; after seeing it you get an impression that Zionism and Jews are the same.”

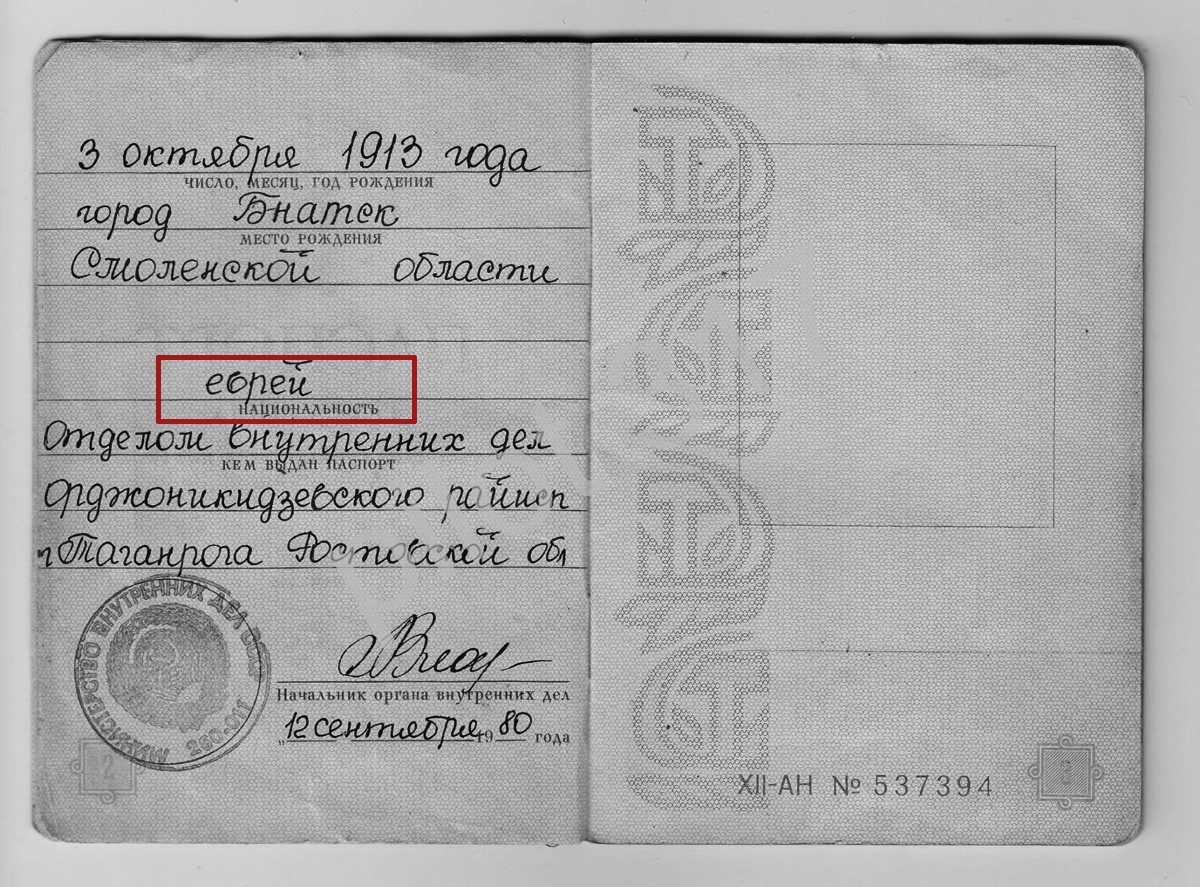

Soviet passport with its infamous "5th paragraph" which says "Jew".

meshok.netStill, being a Jew in the USSR was a tough destiny, especially given that Soviet IDs had an infamous “5th point”, where one had to indicate their nationality. There were paths that a person whose 5th point said “Jewish” just couldn’t take: like becoming a diplomat, or serving in the KGB. Or, for instance, enrolling in the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics of Moscow State University.

“After 1967, there were almost no Jews who managed to enter the faculty… the most talented of them, who had won math Olympics, were offered extremely difficult tasks in the entrance exams,” publicist Mark Ginsburg recalled. “Academic Sakharov (Andrei Sakharov, the famous physicist and human rights activist) said that it took him an hour of hard work to solve a mathematical problem given to Jewish enrollees who had only 20 minutes to handle it.” Such policy wasn’t state-sponsored: as many sources note, it was the initiative of faculty’s leadership. But the state did nothing to make MSU inclusive.

Many Jewish parents tried to make their children’s lives easier, describing them as Russians (Ukrainians, Tatars etc.) if they were half-bloods. But it didn’t always work. A popular saying went: “If something happens, they will punch you in the face, not in the passport.”

Jewish students in the USSR, 1979.

Sergei Metelitsa/TASSAny mention of Jewish heritage was forbidden – even in such a delicate matter as the Holocaust which the Soviet state never referred to. “No monument stands over Babi Yar,” poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko wrote concerning the massacre site of more than 100,000 Jews by Nazis in Ukraine in 1941, and he was right – the USSR never recognized any special ‘anti-Jew’ mass killings, insisting that all Soviet citizens suffered equally during the war.

Growing up in such a negative atmosphere, young Soviet Jews didn’t feel so good about the USSR. At the same time, Israel was growing stronger, defeating Arab states in the wars of 1967 and 1973 and protecting its independence. “An image of a victorious country appeared. And Soviet Jews started thinking: here, they are ashamed of their nationality… and in Israel, they are proud of being Jewish,” journalist Leonid Parfyonov said in his film Russian Jews. Thus, the idea of immigration became very attractive.

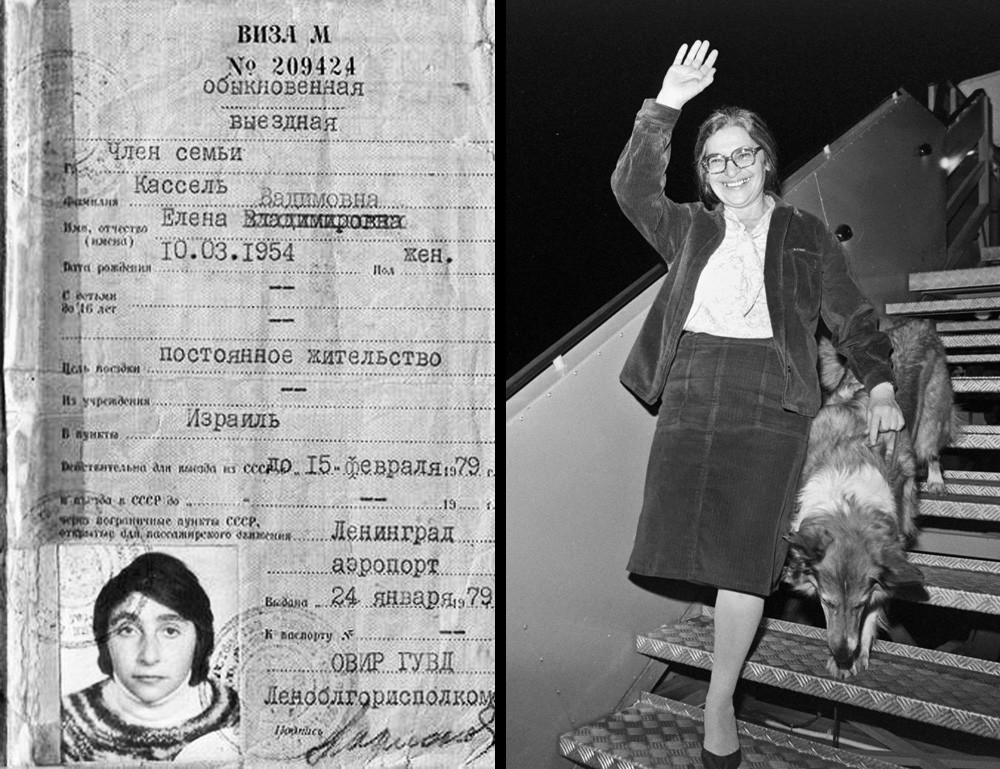

Left: Soviet passport with an exit visa. Right: Ida Nudel, one of the Jewish immigrants (previously imprisoned in the USSR) steps onto the Israeli soil.

Elena Kassel; Nati Harnik/National Photo Collection of IsraelDuring the 1950s to early 1960s leaving the USSR was hardly an option for its citizens: one had to get an exit visa which required going through bureaucratic hell (for instance, getting the approval of your boss and party official) and paying a fee equal to the price of a new car. But by 1970, the state loosened its grip.

There were several reasons. Détente in the relations with the U.S. (in 1972, President Richard Nixon paid a visit to Moscow) made the Kremlin do something to silence the voice of those in the West bashing the USSR for its lack of human rights. Plus, there were internal protests. On February 24, 1971, a group of 24 (desperate) Jews who had been denied permission to leave the country occupied the building of the USSR's Supreme Soviet demanding their right to leave. Because they managed to attract the attention of the foreign press, the government let most of them out.

Later, Soviet policy towards Jewish immigration shifted several times, with relative freedom in the 1970s and harsh restrictions in the 1980s. But generally, Jews became a nation so unwelcome in the USSR that the communists preferred to get rid of them by, basically, letting people go. Between 1970 and 1988, 291,000 Jews and members of their family left the USSR, settling down in Israel, the U.S. and other countries of the world. Perhaps they missed their homeland – but not the communist party.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox