In Kherson, in 1897, Vadim Butmi de Katzman was cleared of the crime of putting three bullets into Oyzer Dimant, a famous money lender. A fiery speech was delivered by the defendant’s attorney, during which he accused the dead loan shark of his draconian interest rates, which were, apparently, enough to drive a man to murder.

This was to illustrate that Russia has always had a passionate hatred of lenders and loan sharks. But no society can live without some form of borrowing and lending. How did such a system come about in Russia? And why was its fate sealed from the start?

Insides a Russian office of the 17th century (contemporary reconstruction in Kolomenskoe resort, Moscow)

kraeved1147.ruThe Orthodox Church always forbid its servants from taking part in money-lending lest they be excommunicated. But life in the Russian Empire always imposed its own conditions for survival.

In the Old Rus’, monasteries and churches were the only truly safe refuge, one where no bandits or robbers – nor even the Tataro-Mongols, thanks to their famous promise to preserve the dignity of places of worship – could ever set foot. Your land and everything on it could be taken away by some prince or the gangs, while your business faced the same fate in the event of a war. The church remained your only place for safely storing one’s assets. Stone churches and monasteries were especially good in an age when wood was a popular material, and fires were frequent.

The vast majority of Russians of all standing in the 16-17 centuries could barely make ends meet. Poverty was rampant. The churches understood that they were the only creditors in town, and so, people would come with requests to borrow money, often in exchange for a down payment in the form of personal belongings. Despite the Church’s – and even the Tsar’s – opposition to any sort of monetary dealings, monasteries carried on in their role as chief credit institutions.

Solovetsky Monastery

Sergey Shimansky/SputnikOne way to avoid paying was military service or manual labor. Another option would have been to pawn your property – land, gold, weapons, jewelry, cattle and so on.

Interest rates used to be astronomical, up to 20 percent. The situation was exacerbated by the peasants’ inherent religiosity: the thinking was that if you couldn’t pay up, you were denied passage to heaven. And if the borrower continuously failed to make good on their debt, the lender could actually threaten to tear up the debt paper, which would undoubtedly have struck fear into the heart of anyone with a religious bone in their body.

By the 17th century, these practices had grown into a whole financial system: there was a secondary debt market (monasteries would buy the peasants’ and merchants’ debts off of each other), and a separate percentage to be paid on percentage of debt. And if a peasant refused to pay up, he would himself become the monastery’s property. However, such a system had contained no checks and balances whatsoever to prevent abuse by the very people that sustained it.

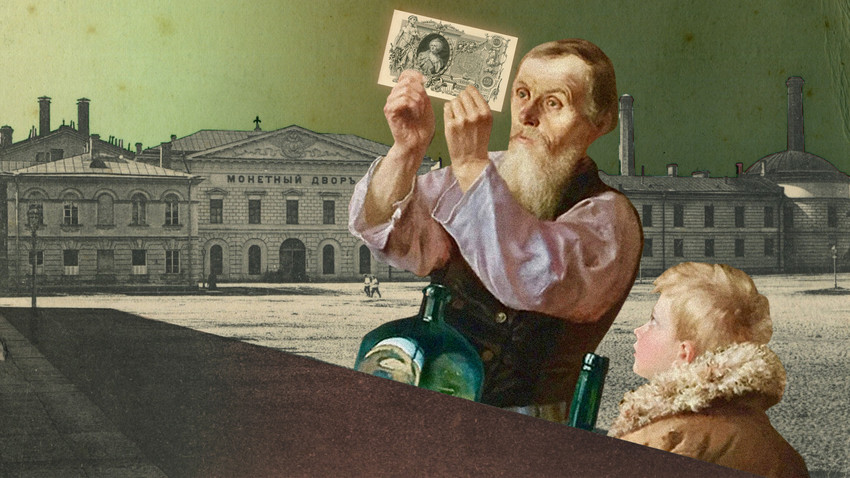

The building of the St. Petersburg Mint

Archive photoThe state was not in the best position with such a system. By pawning their lands together with the peasants, wealthy landowners couldn’t contribute enough soldiers for the army. The tsar was forced to create a regular army and increase amounts of land given to landowners for their state service. This had led to economic decline, and toward the end of the 17th century the church had owned almost a third of all arable land in Russia.

Peter the Great put reforms in place to combat the church’s power (including confiscating lands), however, despite successfully ousting the church from its monetary throne, Russia still didn’t have dedicated credit institutions – and we were spending mountains of gold on war and development. Peter himself borrowed money from European lenders (the Medici clan among them). Meanwhile, the assorted aristocrats and entrepreneurs of Russia had themselves become lenders.

Empress Anna in 1733 demanded the St. Petersburg Mint to give loans at a fixed rate of eight percent. However, even with this law in place, only the richest and most well-connected aristocrats could even afford to borrow from the Mint – its starting capital was tiny, and the Mint couldn’t invest money in trade or production, like a proper bank would have done. Traders and minor landowners borrowed from each other. As for the peasants, they weren’t even active participants, only opting to do business with their landlords, if at all (the first peasant bank would only appear in 1882).

Meanwhile, the landowners had themselves been spending a lot of money, but only received payment from their estates once a year. So they were in constant need of loans.

The building of the Noblemen's Bank in St. Petersburg

Archive photoEmpress Elizabeth issued a decree on establishing proper banks in 1754: The Noblemen’s Bank and the Merchants’ Bank. However, the institutions were still low on finances. An average nobleman in Russia could easily rack up a 10-15 thousand card debt at a time when the entire wealth of the Noblemen’s Bank stood at 750 thousand rubles. They simply couldn’t continue spending this way, especially when the whole point of their own bank even being created had been to save them from poverty: Russian nobility was absolutely instrumental in their role as commanders of armies and in staffing governmental structures.

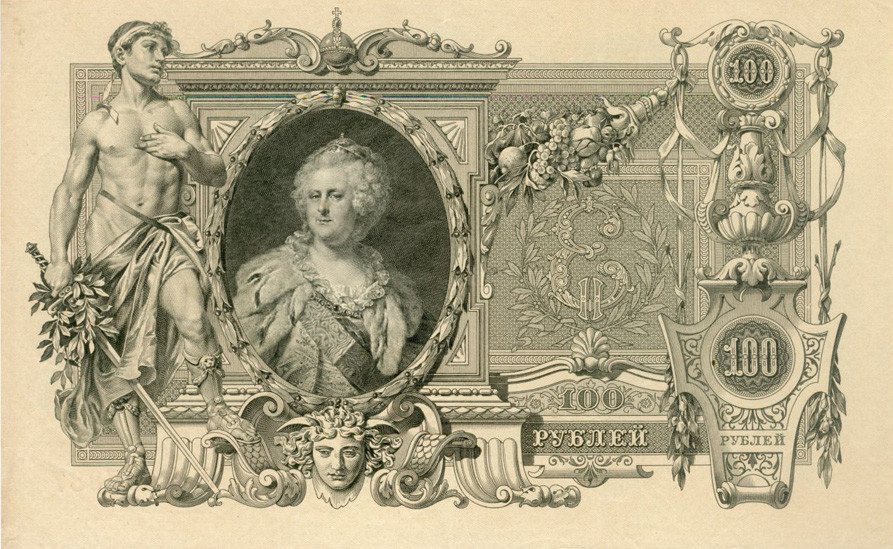

The nobility, of course, understood this, and wasn’t quick to return money. To owe money at the time wasn’t something to be ashamed of – and nobody could force the wealthiest of the aristocrats to pay up… it’s not like the Empress herself was going to come knocking. Grigoriy Orlov – a lover to Catherine the Great – would ask her on average of 5-10 thousand rubles weekly. The Orlovs’ palaces were also being built using state money. Even the richest man in the empire – Grigoriy Potemkin, would borrow money and not pay back. The man could rack up a 3,5 million rubles debt on just a single occasion!

100 rubles of Catherine the Great

Archive photoIn short, Russian nobility learned to live in perpetual debt. They owed money all over the place. And that’s where the banks came in: you borrowed a large sum, and used it to pay off all your debts. You ended up owing to a single institution.

It’s not hard to imagine that such a system was unworkable in the long run. It was putting the entire economy in danger of ruin. By 1782, the Merchants’ bank was merged with the Noblemen’s, while just four years later, the latter was liquidated and the State Credit Bank was opened. These mergers and the new names that went with them were still powerless to tackle the system’s core flaws.

Moscow Merchants' Bank, 1903

Archive photoTo be a nobleman in the Imperial guard at the dawn of the 19th century was not cheap. The aristocrat had to buy the whole kit from the ground up: from the gold-studded uniform to the horses and the weapons, guns – everything. On top of that you had to have a spacious apartment and an entourage. Coming up short in any department could result in a reprimand and even cost one his career. The royal guard regiments ended up being staffed by nobility whose parents had regularly sent extra money on top of the army wage. And despite a colonel’s annual wage of 1200 rubles being a reasonable enough sum, in those days some 10-15 thousand rubles could easily be spent on things like dowry.

The government did everything in its power to preserve aristocracy in Russia. The annual interest rates at the banks were lowered to just 4-5 percent, while confiscated lands – in the event of a debt not being paid – were “taken into custody”, instead of confiscated for good. Despite a number of measures aimed at sustaining upper-class lifestyles, a healthy attitude towards money and spending never really took off in Russia. Even something as small as believing that your debt was to the tsar – and not to the state – would have a detrimental effect: a noblemen reasoned that he did not need to repay the tsar, since he’s serving ‘the state’ anyway, as a member of the guard or a civil servant.

Except that by 1763, nobility was no longer compelled to serve. They could live out their lives in their mansions. And so they did… aside from the small matter that they had by then been living on lands that were pawned or ‘confiscated’ several times over. It made no difference. By 1850, more than two-thirds of Russia’s lands (with peasants) had been in ‘custody.’

The building of the State Bank of Russia in St. Petersburg

Tovarischestvo "Obrazovanie"In the 19th century, the government came up with a variety of new financial institutions. Notably, the State Bank of the Russian Empire (founded in 1860) was chaired by Aleksandr von Stieglitz – a foreigner, and the son of Ludwig Stieglitz, the most trusted banker in 19th century Russia.

The main function of the state bank was to bail out the state itself, as well as bankrupt commercial banks and, finally, the aristocracy. At first, loans were being given to the treasury: by 1879, it owed the State Bank 478,9 million rubles. That’s with a state budget of 628 million. The debt took 22 years to repay, which was done in 1901.

By the time serfdom was abolished, Russia’s entire aristocracy had suddenly found themselves in possession of securities. But the nobility failed to become players on the stock market – they simply cashed in and spent the money abroad.

Nevertheless, following the reforms, a credit institution boom swept over Russia. From 1864 to 1872, some 33 joint stock banks and 53 mutual credit institutions were established, and with them mortgage banks, which the nobility used to pawn the remainder of their lands – with deadlines as long as 50 years and annual rates that relentlessly plummeted to just 3.5 percent by 1897.

The history of Russian banking in the latter half of the 19th century is a complicated, but unsurprising one – not when your entire banking system exists to serve the needs of the state and the super-rich. In 1917, the sum total of money borrowed by the government for war expenses came up to 90 percent of the entire balance of the State Bank.

Despite the State Bank of Russia being among the most active in Europe (in terms of the number of operations), it never became financially viable. The main reason for the failure of the Russian credit system lay in the patent dishonesty of Russian aristocracy – which comprised both the state and the military, while simultaneously pursuing their own private interests.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox