Marriages between monarchs and their children were always considered a powerful tool that helped to wage fewer wars and preserve peace between countries, as well as strengthen their own kingdoms, and international marriages were common between powerful dynasties. The first Russian prince who understood this was Yaroslav the Wise (978-1054), the Grand Prince of Novgorod and Kiev and son of Vladimir the Great (the prince that Christened the Russian lands). Yaroslav the Wise himself married Ingegerd Olofsdotter of Sweden, daughter of Olof Skötkonung, the first Christian king of Sweden. They had three daughters, and all three of them were married to foreign princes and kings.

'King Salomon Being Cursed by his Mother Anastasia' by Soma Orlay Petrich

Déri MuseumWe don’t know the real name of the eldest daughter (1023-1074/1094) of Yarolsav the Wise. In 1038, she married Hungarian prince Andrew (Andrash), who became the king of Hungary in 1046. By his side, she survived a dynastical war between Andrash and his brothers, and even ruled the country for a considerable time, while her husband was bedridden by illness; but her days ended in German lands, where she went following her exiled son Solomon. She is mentioned as Anastasia in a 15th-century Polish chronicle, so this name has stuck since.

Daughters of Yaroslav the Wise as depicted on a fresco in Saint Sophia's Cathedral, Kiev (from left to right): Anna, Anastasia, Elizaveta, Agatha

Public domainHistorical sources have preserved much more information about Elizaveta (1025-1067?), the second daughter of Grand Prince Yaroslav. Born and raised in lavish conditions in Kiev, she had a good education. Her future husband Norwegian prince Harald (1015-1066) had been seeking to marry her from a young age, but Yaroslav the Wise at first considered him not worthy enough for his daughter.

Aiming to prove his worth, Harald went to serve Yaroslav as a mercenary and military commander. After that, Harald warred for the Byzantine Emperor and gained considerable amounts of loot that he sent to Yaroslav. Harald also sent his fiancee poems that described his wartime feats, but deemed them worthless, because Elizaveta “wouldn’t want to acknowledge him”. In 1043/1044, after another successful military campaign that ended in a peace treaty between Yaroslav and Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX, Harald finally gained Yaroslav’s approval to marry Elizaveta. They then moved to Norway, where Harald became king in 1046.

Harald of Norway. Window with portrait of Harald in Lerwick Town Hall, Shetland

Colin Smith (CC BY-SA)Harald ruled with an iron fist, and gained a nickname Hardråde, roughly translated as “hard ruler”. Elizaveta bore him two daughters, Maria and Indigerd, but in two years, Harald abandoned her for a consort, Tora Torbergsdatter, who bore him two sons, Magnus and Olaf, who later became subsequent kings of Norway.

What became of Elizaveta is unknown. But one of her daughters, Indigerd, became a powerful woman: she was the wife of Olaf I of Denmark, and after his death in 1095, married Philip, who was the king of Sweden until 1118. The year of Indiegerd’s death is not known.

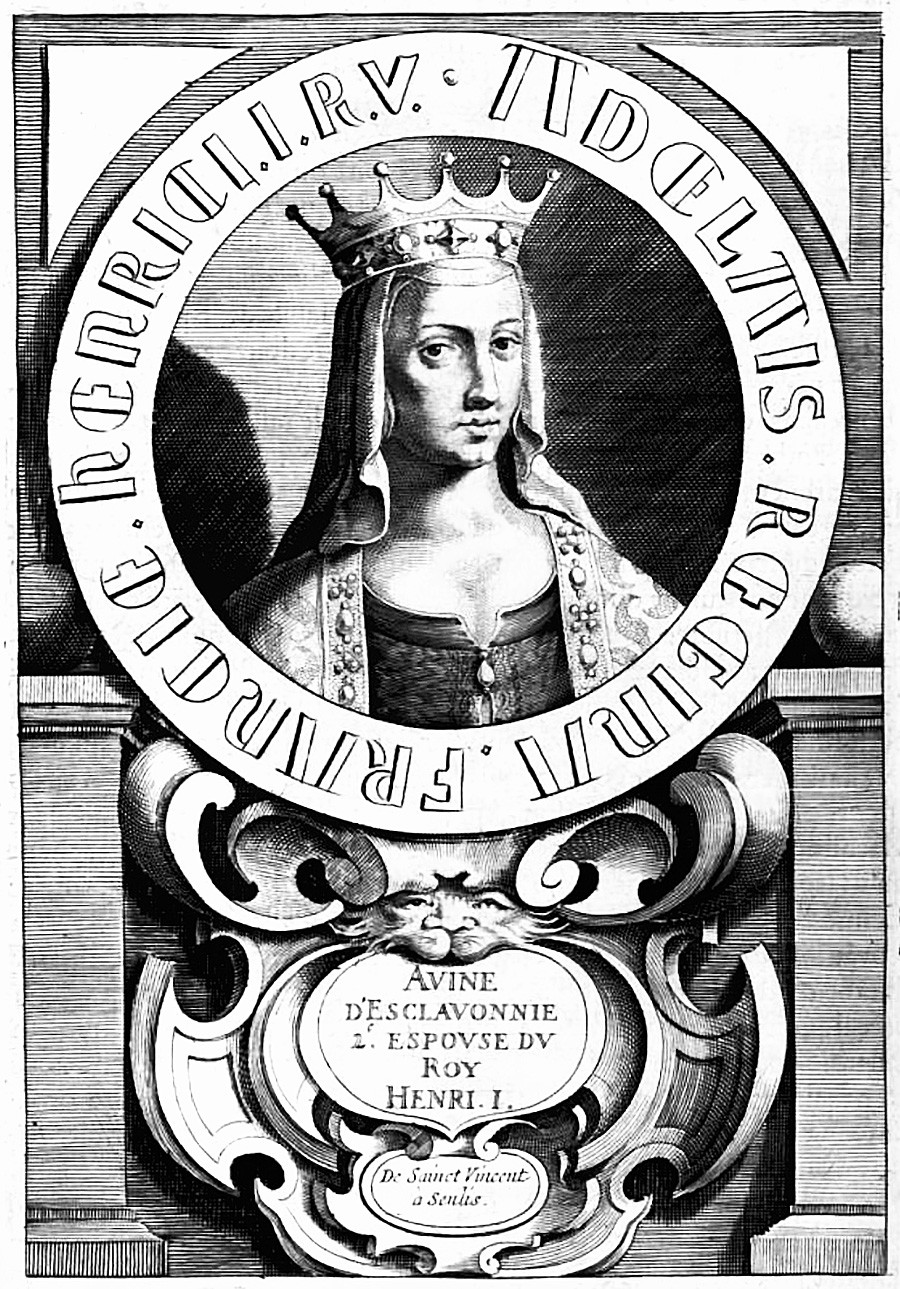

Anna, Queen of France. From the book "Histoire de France, depuis Faramond jusqu’à maintenant," Paris, 1643.

Public domainThe youngest of Yaroslav’s daughters, Anna (1032-1089), married Henry I of France (1008-1060) in 1051. This marriage brought the French king no new territories, but a very rich dowry, and more importantly, Anna gave birth to Philipp I (1052-1108), the next king of France, as well as three other children.

After Henry’s death, Anna abandoned her children and became the wife of Ralph IV of Valois, which enraged the Catholic church. However, Anna was revered as the king’s mother until her death around 1089.

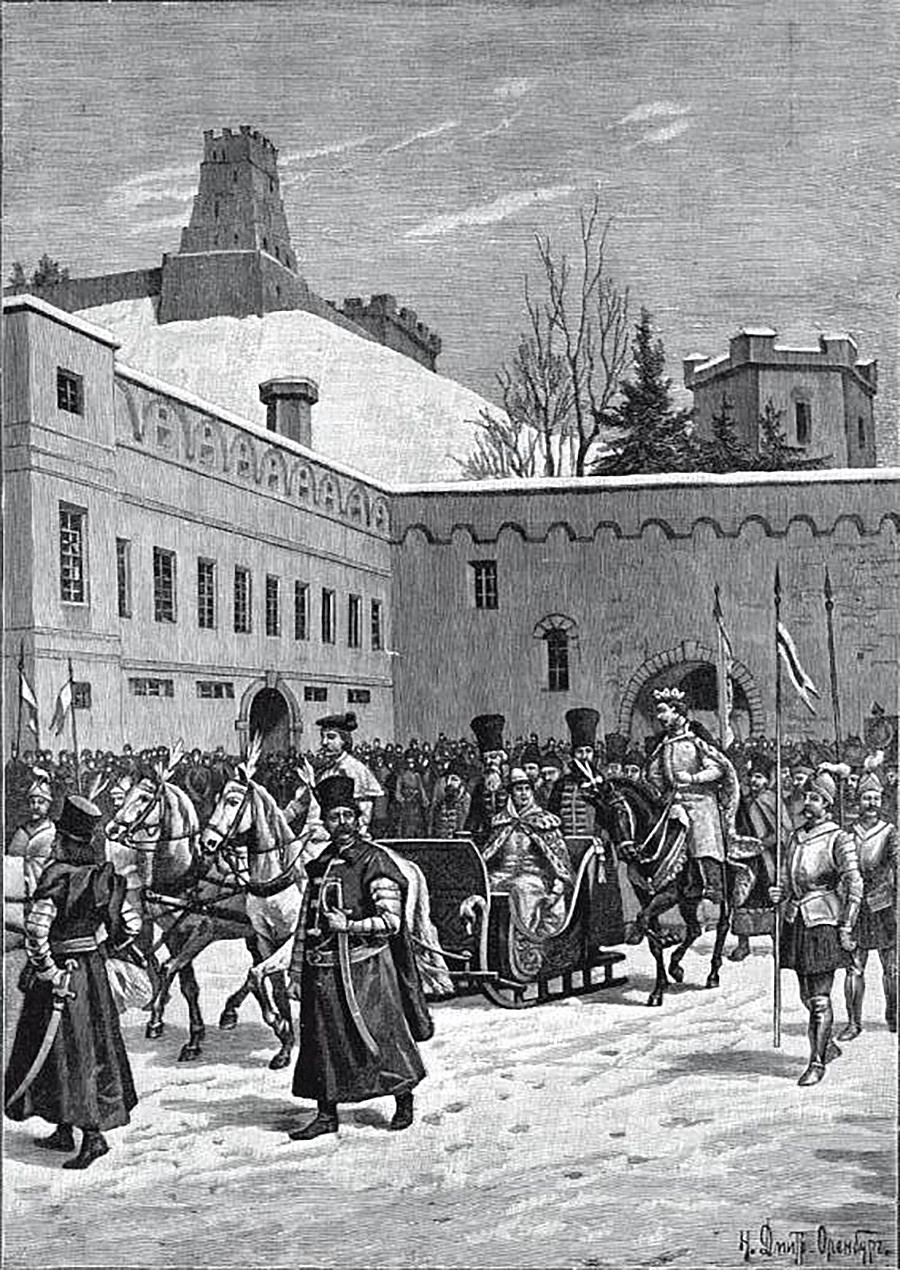

Alexander I Jagiellon meets Helena Ivanovna in Vilnius in 1495, by Nikolay Dmitriev-Orenburgsky

Public domainFor a long time after Yaroslav the Wise’s reign, Russian princesses didn’t marry foreign princes and kings – because the Russian lands were becoming increasingly Orthodox Christian, and thus didn’t allow Orthodox princesses to marry kings who professed to Catholicism. However, another Russian princess who married a foreigner was also born from an international marriage. Ivan the Great, Grand Prince of Moscow (1440-1505), who ruled the Russian lands longer than anybody in history, was married to Zoe Palaiologina (Sophia in Russia), a Byzantine princess.

Their daughter, Helena Ivanovna (1476-1513), married Alexander I Jagiellon (1461-1506), Grand Duke of Lithuania and later also king of Poland. Ivan the Great was firmly against Helena being converted into the Catholic faith of her husband, but Ivan needed this marriage as a means of keeping peaceful relations with Lithuania. Helena kept her faith and became the patron for the Orthodox people of Lithuania – but she was never crowned properly as a Catholic queen.

Alexander and Helena

Public domainUnfortunately, she and Alexander of Lithuania didn’t have children (Helena suffered two miscarriages), And in 1506, Alexander died, asking in his will for the monarchy to protect his widow. Helena lived in Lithuania, but in 1511, she wanted to go back to Russia, where her brother, Vasili III Ivanovich (1479-1533) was ruling. But Helena’s fate was grim: Sigismund I the Old, the next ruler of Lithuania and Poland, didn’t allow her to leave Lithuania and arrested Helena while she tried to flee, notwithstanding her brother’s protests. She died in Lithuania (while still trying to escape) at the approximate age of 36 and was buried in Vilnius. But her death became the reason for a war between Moscow and Lithuania, that won Moscow a lot of lands around Smolensk. Eventually, Vasiliy avenged his sister’s tragic death.

Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna of Russia (1783-1801), Palatina of Hungary

Gatchina Museum ReservePaul I of Russia (1754-1801) wasn’t Russian by blood – both his parents, Peter III and Catherine the Great, were German. His eldest daughter, Alexandra (1783-1801), was also German, as Paul’s wife, Maria Fyodorvna, belonged to the House of Württemberg.

Her grandmother, Catherine the Great, had plans for Alexandra, brilliantly educated and brought up in the highest royal fashion. She was to become an important piece in the game of European thrones Catherine was waging. In 1792, when Alexandra was just 9, plans commenced to make her Queen of Sweden by marrying Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden. Years went by in negotiations, but the Swedes insisted on Alexandra being converted into Catholicism and didn’t want to make any compromises. So the marriage was canceled.

Habsburg-Lotharingiai József Antal János (1776-1847) by Miklós Barabás

Public domainSeveral years later, in 1798, when Paul was Emperor, he made plans for a military union with Austria against Napoleon. To strengthen this union, Alexandra Pavlovna was to become the wife of Archduke Joseph, Palatine of Hungary (1776-1847), brother to Francis II (1768-1835), the last Holy Roman Emperor. This time, the princess was allowed to keep her Orthodox faith. But she was far from happy. The royal lady-in-waiting, Countess Varvara Golovina, remembered that before her departure, Alexandra was sad, and her father was grieving, too: he kept saying he was seeing her for the last time.

It turned out Paul’s prediction was true. In Vienna, a cold reception awaited Alexandra. Debates about her changing her faith recommenced, and the Austrian court openly displayed disdain for the Russian princess. Her husband couldn’t do anything, because he didn’t have a voice in the presence of his elder brother. When Alexandra became pregnant, her condition wasn’t good. The birth didn’t go well, either: her daughter died shortly after birth. On March 4, 1801, 3 days after her father was murdered in Russia, Alexandra passed away.

Queen of the Netherlands, Anna Pavlovna of Russia (1795-1865) by Jan Baptist van der Hulst

Public domainAnna (1795-1865), Paul and Maria’s 6th daughter, was brought up in the family of her elder brother, Emperor Alexander of Russia. When she was 15, Napoleon Bonaparte asked for her hand, but Alexander refused, which enraged the French emperor. Frederick William III of Prussia and Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, were also interested in Anna’s hand in marriage, but their advances were refused as well.

Only William, Prince of Orange (1792-1849), was deemed worthy enough for the princess. She married him in St. Petersburg in 1816. Anna had a huge dowry, probably the richest one in Europe. The list of items took up 46 pages.

Queen of the Netherlands, Anna Pavlovna of Russia

Royal Collections of the NetherlandsIt was a rare occurrence, but Anna and William apparently actually loved each other. They had 4 sons and a daughter. In 1824 and 1833, they visited Anna’s family in Russia, and in 1840, William became king: William II of the Netherlands. He died in 1849. However, Anna outlived him. In 1853, she visited Russia again and died in 1865, being the last surviving child of Paul I.

Princess Olga von Württemberg by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (1805–1873)

Landesmuseum WürttembergThe third child of Nicholas I of Russia (1796-1855) and his wife Alexandra Fyodorovna, Olga (1822-1892) was brought up in a friendly and supportive family and educated by celebrities, including Russian poet Vasiliy Zhukovsky, who translated Homer’s Odyssey and famous sculptor Ivan Vitali.

As most of our heroines in this article, Olga was a bride one could only dream of, and many marriage offers were refused by her or her family. Even though her father allowed her to choose anybody she wanted, Olga herself said she was in no rush to get married. She was rumored to have had some flings and even fell for different European royalties, but those romances never ended with marriage.

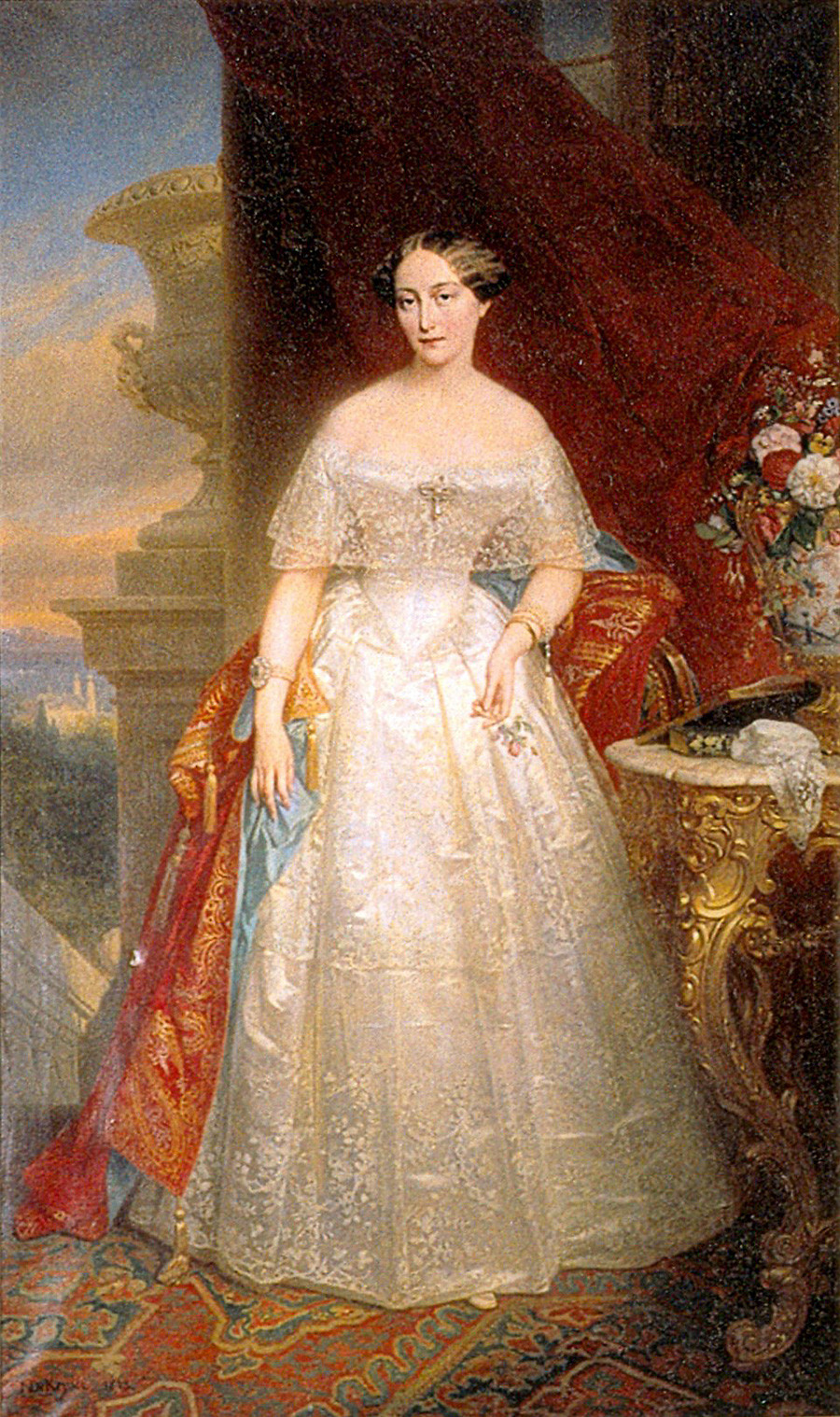

Portrait of Olga of Russia (1822-1892), Princess of Württemberg by Nicaise de Keyser

Public domainIn 1846, when Olga was 24 (a late age for marriage during those times), she met Karl Friedrich Alexander of Württemberg (1823-1891). Although they were second cousins, this didn’t stop them from falling in love and marrying within the same year. But Russian society eyed the marriage warily – Karl Friedrich had a rotten reputation. They were often dubbed “Beauty and the Beast”.

The couple moved to Stuttgart, the capital of Württemberg. They had no children, perhaps because of Karl's homosexuality that he didn’t even try to hide. But it is rumored their family life was peaceful and merry. In 1864, Karl’s father died, and he became Charles I, king of Württemberg.

In 1870, Olga and Karl adopted Olga's niece Vera Konstantinovna, the daughter of her brother Grand Duke Konstantin. As the queen’s consort, Olga devoted a lot of time to charity, which earned her reverence among the people of Stuttgart. She died in 1892, outliving her husband by a year.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox