The whole of Europe feared these ferocious bearded cavalrymen, armed with pikes and sabers. Known also for their wild temper and superb fighting prowess, the Cossacks will forever be an integral part of Russia’s mystique.

The Cossack irregular cavalry was a source of envy and admiration for many countries that dreamed of having such units in their own armies. One of them even turned to Russia for assistance to set up its own Cossack military formation. This was Iran, still officially known as Persia until 1935.

The Persian ruler, Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar, first saw Cossack warriors during a visit to Erivan (Yerevan) in 1878. He was struck by the fighting skills and regimentation of the so-called Terek Cossacks, who lived in the Caucasus region.

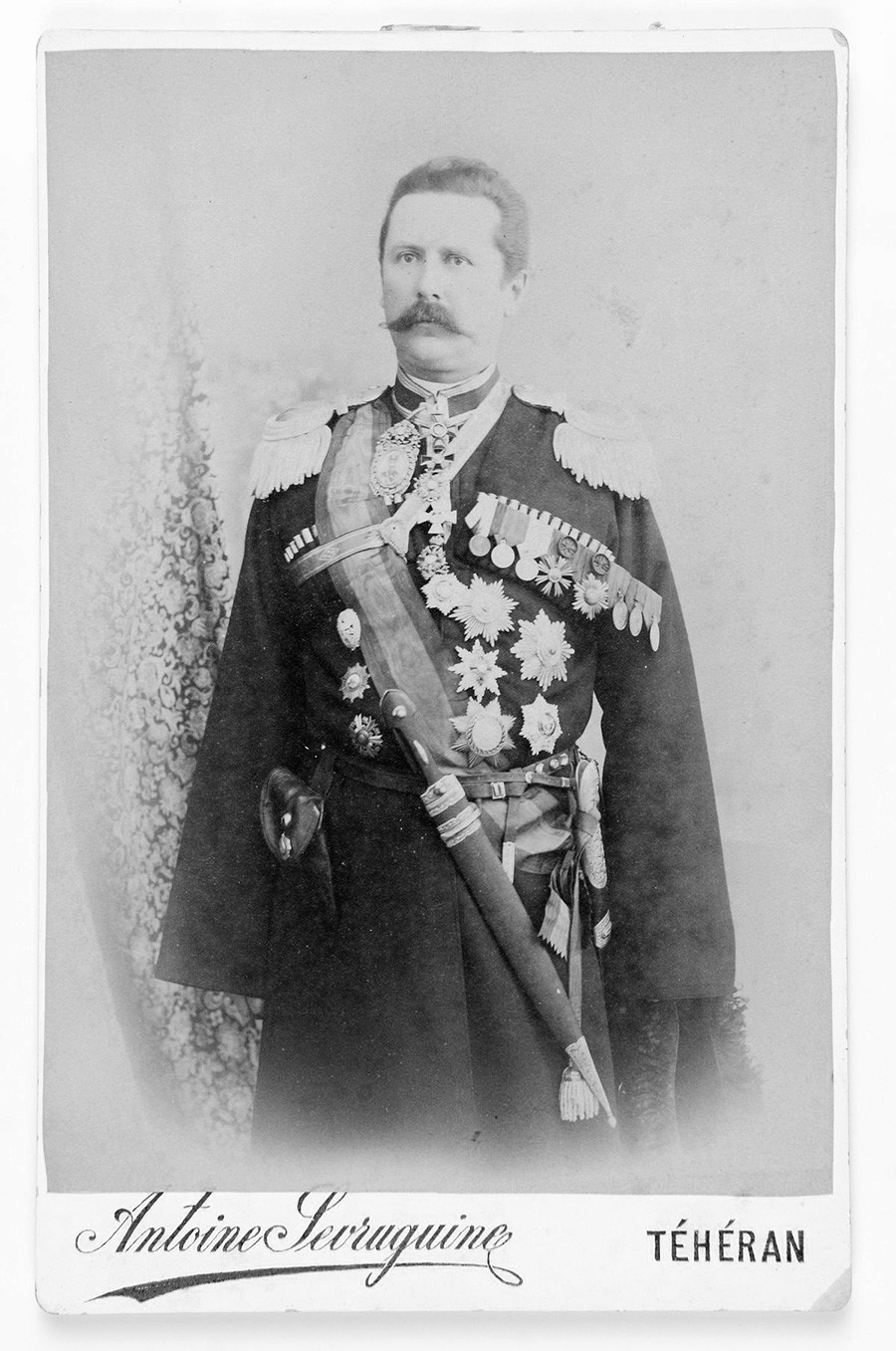

Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar of Persia, 1873.

Getty ImagesBurning with desire to create something similar in his own land, the shah officially requested Russian assistance to set up a cavalry detachment. Emperor Alexander II immediately gave his consent.

It was a no-brainer. For many years, Russia had been shadow-boxing with the British in the Great Game — a 19th-century version of the Cold War. The prize was influence in Asia, and Persia was a crucial piece in the sprawling jigsaw puzzle. The shah had handed Russia a priceless opportunity to consolidate its position in the country, and the chance could not be wasted.

Lieutenant Colonel Alexei Domontovich was duly dispatched to Iran, together with three other officers and five non-commissioned officers from the Terek Cossack army.

Formed from Persian troops in 1880, “His Majesty the Shah’s Brigade” initially numbered only 200 soldiers. The Persian Cossacks were dressed in the uniform of the Terek and Kuban Cossack units, with local insignia.

The brigade was headed by an officer of the Russian General Staff, the shah’s closest adviser, who was subordinate only to the ruler himself and the country’s prime minister. He was conferred the prestigious title of sardar — considered a higher rank than general. The shah presented him with the ribbon of the Imperial Order of the Lion and the Sun and the Timsal — a portrait of the shah adorned with diamonds to be worn on the chest. The Persian ruler never interfered in the internal affairs of the brigade, relying solely on the opinion of its commander.

Over time, the brigade expanded numerically and became more complex structurally, being supplemented with an infantry battalion and an artillery battery. Now a genuine fighting force, the Persian Cossacks were tasked with protecting the shah and senior officials. They ensured the security of ministries, diplomatic missions, and banks, and assisted in the collection of taxes and the suppression of unrest.

All the same, the brigade had a checkered history, full of highs and lows. The shahs swung from total disinterest — to the point of disbanding the brigade — to showering it with all kinds of favors, and back again. Throughout it all, Russia continued to partially fund the unit.

In the early 20th century, it was the most combat-ready unit in the Iranian army and given priority in terms of equipment. “When I joined the brigade in 1914, I found good buildings with everything one needed, a fine house for the brigade commander, and decent apartments for the Russian instructors, well furnished and with all amenities,” recalled Junior Captain Leonid Vysotsky, who was sent to Iran as a cavalry instructor.

A cadet corps was even set up under the brigade, in which training was conducted mainly in Russian, with a handful of subjects (in particular, Persian literature) in Farsi. On completion of their training, the cadets — reared in the Russian spirit and speaking good Russian — were enlisted as officers.

According to military journalist and intelligence service historian Mikhail Boltunov, the deployment of a Cossack brigade in Persia under the leadership of Russian officers was one of the most successful special ops of Russian military intelligence in the latter half of the 19th century (Mikhail Boltunov. Undercover Intelligence. A History of the Secret Services. Moscow, 2015).

As leader of the brigade (1894-1903), Vladimir Kosogovsky was able to send vast amounts of strategic, military, and economic intelligence to the Russian General Staff. Occupying a high post, he was well versed in the slings and arrows of Iranian politics.

Kosogovsky meticulously described the optimal route by which the Russian army might advance through Iran to India, the so-called jewel in the crown of the British Empire, detailing the most suitable places for crossing rivers, the best areas for supplying troops, etc.

Vladimir Kosogovsky.

Public domainIn his dispatches to St Petersburg, he even reported on technologies for silkworm cultivation and silk production, and the construction of a water supply and sewage system in the Iranian capital.

At the turn of the 20th century and beyond, the Persian Cossack brigade helped shape many important events in the history of Iran, all the while remaining faithful to the ruling regime. During the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1908, it was solely thanks to the brigade that Mohammad Ali Shah was able to cling on to power (and his life), and emerge victorious from the conflict with the Majlis.

In 1916, a military division was deployed on the basis of the brigade, but by that time the Cossacks’ days were numbered. The 1917 revolution severed all their ties with Russia.

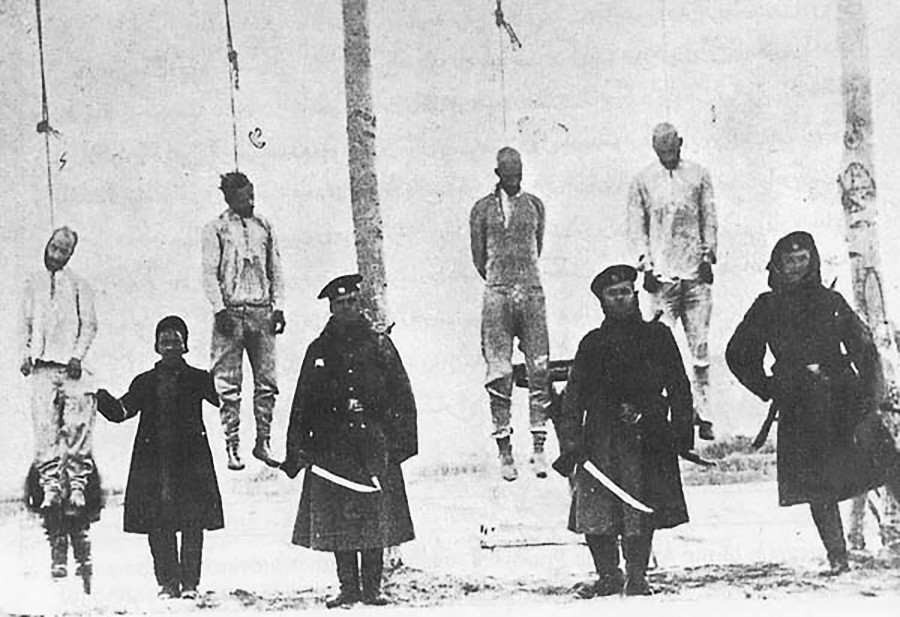

Execution of constitutional activists in Tabriz, 1911.

Public domainFor a while, the division was used to prevent the Soviets from penetrating into northern Iran. However, in 1921, all of its 120 Russian officers were dismissed, and the division itself was disbanded. Nevertheless, the Persian Cossacks trained by Russian specialists were still viewed as Iran’s military elite, and would soon form the backbone of the country’s newly created army.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox