General Augusto Pinochet.

APIn the 1970s, the KGB was so powerful that it managed to manipulate leading media in the capitalist world to benefit its interests. For example, this is the true story about how The New York Times was manipulated during Operation Toucan.

Launched in 1976, the joint operation by Soviet and Cuban secret services was aimed at discrediting, in the eyes of the world, Chilean leader Augusto Pinochet, who regarded Communism as his main enemy.

In the same year, The New York Times published 66 articles on human rights violations in Chile. During this same period, the newspaper devoted fewer than 10 articles to similar problems in Cambodia and Cuba.

In addition, the KGB forged "correspondence" between Pinochet and Miguel Contreras, head of the Chilean National Intelligence Directorate (DINA), which described in detail a plan to neutralize opponents of the ruling regime that were living in exile in various countries. Taken at face value by American journalists, the letters delivered an additional blow to the reputation of the Latin American dictator.

This was the largest and most complex intelligence operation in Soviet history. In 1981, the KGB and GRU [Soviet military intelligence] were entrusted with carrying out Operation Nuclear Missile Attack, [RYAN is its Russian acronym].

The purpose of RYAN was to find out about possible U.S. preparations for a nuclear strike against the USSR and to develop the best strategy to counter such an attack. The Soviet leadership's fears intensified soon after ardent anti-Communist Ronald Reagan came to power in Washington and toughened U.S. policy towards the USSR.

As part of the operation, the activities of Soviet intelligence agents living outside Warsaw Pact countries sharply increased. Surveillance was set up to watch those with the authority to give orders to launch a nuclear missile attack or who were responsible for launching ballistic or cruise missiles, as well as senior officials in the air force command of NATO countries. In addition, a whole network of "sleeper" agents was set up who were supposed to spring into action in the event of a nuclear war.

In 1984, the USSR pulled the plug on this costly operation following the death of those who had launched it: General Secretary Yuri Andropov and Defense Minister Dmitry Ustinov.

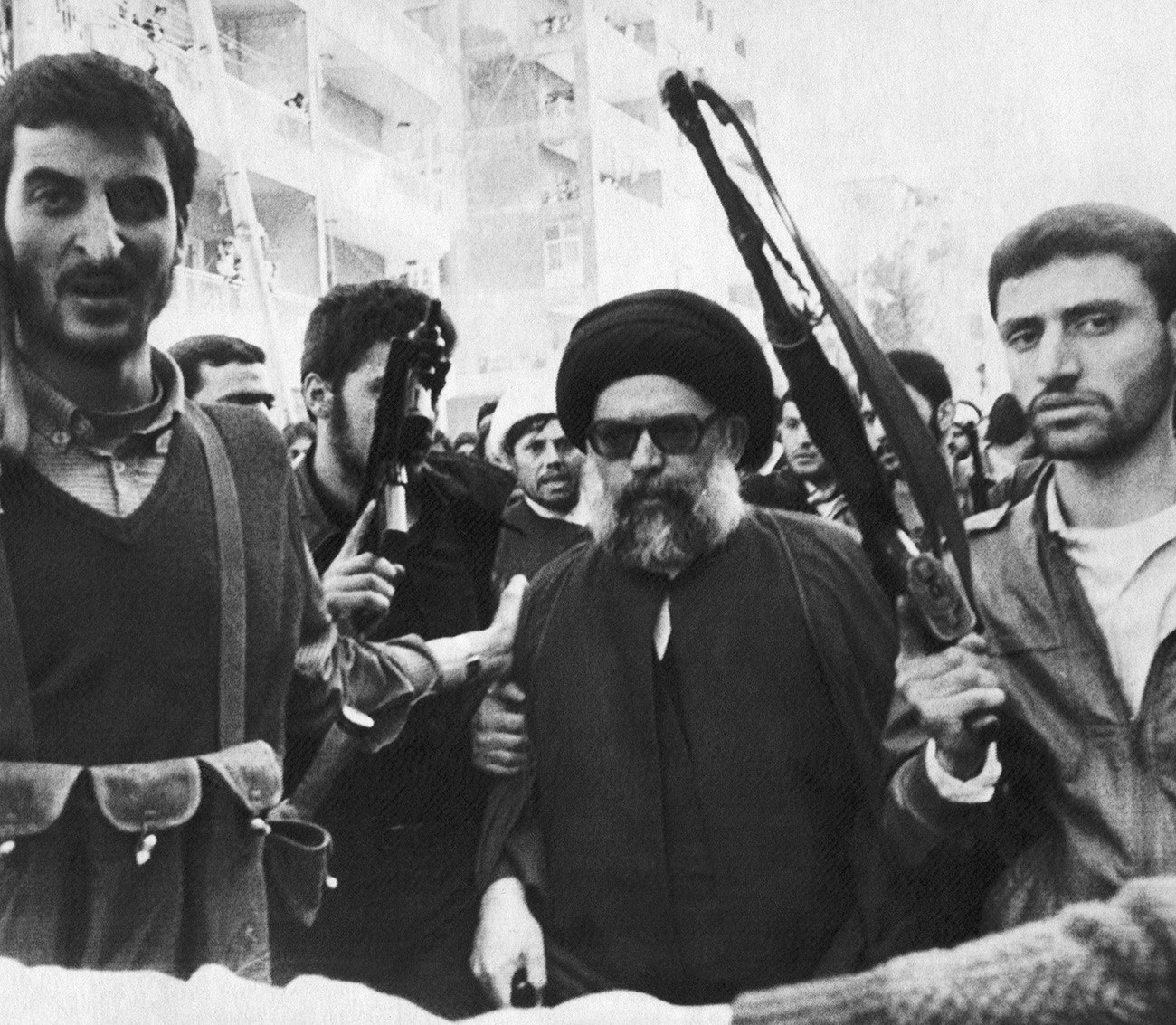

Ayatollah Fadlallah.

Getty ImagesOn Sept. 30, 1985, members of Hezbollah abducted four Soviet diplomats, two of whom were KGB agents, from right outside the Soviet embassy in Beirut. The kidnappers demanded that Hafez al-Assad cancel a security sweep in northern Lebanon that was planned by Syrian forces.

To prove that they meant business, the abductors shot dead one of the hostages. Moscow put pressure on al-Assad, and the operation was stopped. Hezbollah, however, was in no hurry to release the Soviet diplomats, and put forward new demands.

So, the KGB leadership began to look for other solutions to the problem. They established the names of the kidnappers and where the diplomats were being held, but the idea of Soviet special forces storming the building was quickly rejected - it could have provoked an excessive and unwanted backlash. Then, a chance incident helped. In a shootout with the Lebanese military, one of the abductors and the brother of another of the kidnappers were killed. Despite the fact that the Soviet Union had nothing to do with it, there was a rumor that the Russians were surreptitiously settling scores with those who had abducted their diplomats.

The KGB decided to take advantage of the situation, and Yuri Perfilyev, the KGB station chief in Lebanon, met the Hezbollah founder and spiritual leader, Ayatollah Fadlallah, who received the Soviet officer warmly. However, during the conversation he thwarted any attempts by Perfilyev to resolve the hostage problem.

Then, Perfilyev started saying things that in fact he didn't have permission from his superiors to say. He stated that Ayatollah Khomeini's residence in Qom was close to the Soviet border and that, as a result of a possible technical malfunction during military exercises, a missile might accidentally reach Qom. "And God or Allah forbid that this missile should happen to have a warhead."

The threat worked. After a deathly silence, Fadlallah said: "I think everything will be fine." Two days later the hostages were released.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox