Spy or saint? The Buddhist monk who brought Russia closer to Tibet

The life of Agvan Dorzhiev (also Dorjiev) (1853-1938) was a long and interesting one, during which he left a profound mark on the political history of Central Asia in the late 19th-early 20th century and the development of Buddhism in Russia.

Born in 1853 in Khara-Shibit ulus (today in Russia’s Republic of Buryatia), Agvan was interested in religion since he was a child. His education started in Shulutsky datsan (Buddhist university monastery) in Buryatia. He went on his first pilgrimage at the age of 19, first to Mongolia, then Tibet. There he continued his Buddhist education in the Drepung Monastery (one of the “great three” Gelug university monasteries in Tibet) and, after 12 years of studies, received the highest academic title in the Gelug school of Buddhism - Geshe Lharampa.

In addition to perfecting his religious knowledge, he also learned six languages and became one of the few foreigners who managed to make a career in Tibet, attaining the title of “Master of Buddhist Philosophy” (Tsanid-Hambo), and in the mid-1880s becoming one of the seven mentors of the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso. For many years, until the late 1910s, Agvan Dorzhiev was one of Dalai Lama’s closest advisors, being his “debating partner” in philosophy and official envoy to Russia.

A Russian spy?

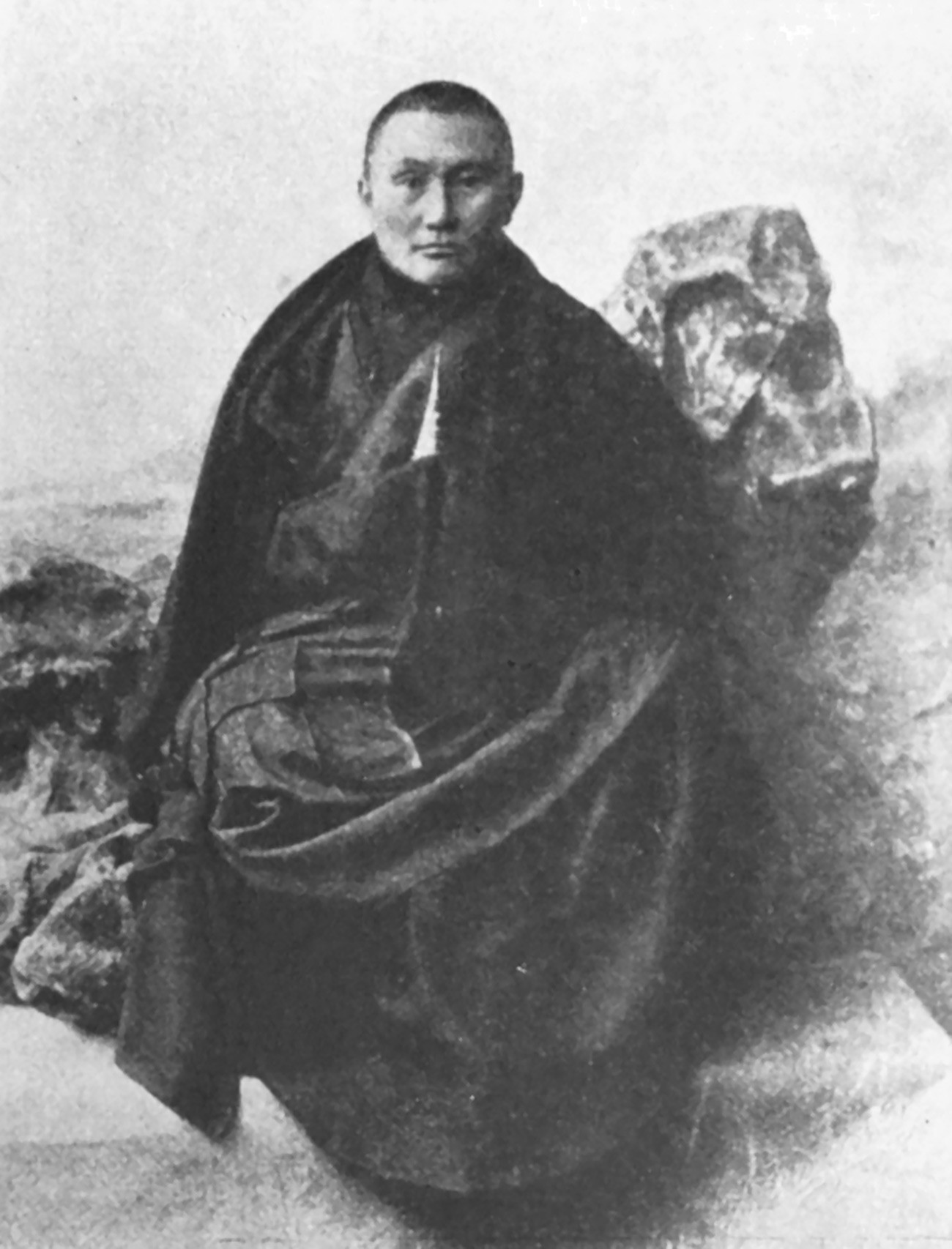

Agvan Dorzhiev

Public domainThe presence of a citizen of the Russian Empire in Tibet couldn’t go unnoticed by the British in India, who were interested in increasing their influence over the territory, which was fighting for local autonomy in the late 19th-early 20th century. The British considered Dorzhiev to be nothing less than a “Russian agent in monks’ clothes” - an understandable assumption, taking into account the confrontation between the Russian and Britain Empires in Central Asia (which existed for most of the 19th century). Yet, the reality seems to have been more complicated.

The Tibetans feared that the British would annex Tibet, which would put the survival of Buddhism at stake. Thus, they sought ways to counterweight such a risk by increasing their contacts with other countries, including Russia. In 1897, the Dalai Lama sent Dorzhiev to France with a secret diplomatic mission, but the visit turned out to be unsuccessful, and in early 1898 he arrived in St. Petersburg where he met with Tsar Nicholas II.

According to some accounts, the leader of the Russian Empire agreed to provide certain support to Tibet and, in 1901, the Dalai Lama’s envoy returned to Russia - this time with six other representatives. "When they returned they brought to Lhasa a supply of Russian arms and ammunition as well — paradoxically enough — as a magnificent set of Russian Episcopal robes as a personal present for the Dalai Lama," British Army officer Frederick Spencer Chapman wrote in 1940.

Agvan Dorzhiev coming out of the Great Palace in Peterhof after his audience with the tsar, 1901

Andrey Terentiev CollectionThe pan-Buddhist

While the Tibetans may have had purely local interests in playing the “Russian card”, some historians are certain that Dorzhiev had broader goals in mind arguing for a pan-Buddhist movement merging all Buddhists into one state under the aegis of the Russian Empire.

“By the 1890s, Dorjiev began to expound the story that the mythical kingdom of Shamba-la, a kingdom to the north of Tibet whose king would save Buddhism, was actually the kingdom of Russia... With their increased physical size and numbers, Buddhists could expect greater security in the Russian empire,” says Helen Hundley of Wichita State University (Kansas).

Dorzhiev’s contribution to the subsequent strengthening of ties between Russia, Mongolia, and Tibet in the 1910s was significant, but many experts agree that he was not anyone’s puppet, as was insinuated in the West. A dedicated pan-Buddhist, Dorzhiev became a key figure in the development of Buddhism in Russia. He encouraged the establishment of datsan schools, paid visits to Buddhist communities and founded the first Buddhist temple in St. Petersburg which opened in 1915.

Following the October Revolution in 1917, Dorzhiev continued to work on keeping Buddhism alive up until the start of Stalin’s repressions. He’d been arrested twice. In 1918 he managed to leverage his contacts to escape, but was thrown in jail again in 1937, on espionage charges, where he died a year later, at the age of 85. While his vision of a greater Buddhist world never materialized, he is still remembered as a great diplomat and a holy man that made a lasting contribution to the development of Buddhism and ties between Russia and Tibet.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox