Russia didn’t have black slaves, or slaves of any kind, for that matter. All the labor needs of the ruling class were met through a system known as serfdom (unlike slaves, serfs owned property and were subjects under law). So, the first black people in Russia performed a different function – they were seen as an object of wonder, a curiosity and something exotic from overseas.

'The Morning of the Streltsy Execution,' 1881, by Vasiliy Surikov (1848-1916).

Tretyakov GalleryIn Vasily Surikov’s painting The Morning of the Streltsy Execution, behind young Tsar Peter there is a carriage upholstered in red velvet and, inside it, a female face is visible: One of the royal women has come with Peter to see the execution. And on the running boards of the carriage are two black pages (servants) in turbans with blue feathers.

Could one of them be Abram Gannibal (1696(?) – 1781), best-known as the great-grandfather of the great poet Alexander Pushkin? Unlikely. Whether Gannibal was brought by Peter from Europe in 1698, or given to him as a gift in 1705, he was never a member of the retinue of the tsarevnas (Russian princesses). Does that mean that having black pages was already a tradition at the end of the 17th century? Yes, it does, and the names of Tsar Peter’s first black pages when he was young and lived in Moscow are mentioned by historian Ivan Zabelin. They were Tomos, Sek and Abram. Unfortunately, this is all we know about them.

Peter the Great with his page Abraham Hannibal, ca 1720.

Victoria and Albert MuseumIn the retinues of European kings, black servants first appeared at the time of the Crusades. They were also employed in this capacity in Russia. There is evidence that there were Moors residing in the apartments of Sister Martha, mother of first Romanov Tsar Mikhail Fyodorovich (Michael of Russia). In the female half of the palace, black people performed the same function as dwarfs, holy fools and wandering pilgrims - they were objects of astonishment and entertainment for the bored women of the royal family forced to spend almost their entire life locked up in their private quarters.

The Tsars, too, kept Moors for entertainment. According to a historian of Moscow, Ivan Zabelin, Mikhail Fyodorovich had Moor Murat and later Moor Davyd Saltanov residing at his court, on whom he lavished sumptuous clothes. Among Tsar Michael’s servants were Moors who had arrived in Russia as elephant handlers (Oriental rulers loved to give elephants as gifts to Russians). According to records, in 1625 and 1626 a Moor named Tchan Ivraimov “entertained” the tsar, showing him the tricks his elephant could perform.

'Portrait of Ivan Hannibal, Abram Hannibal's son' by Dmitry Levitsky

Palais de PavlovskA black woman lived at the court of Michael’s consort, Tsaritsa Eudoxia, and Alexei Mikhailovich (Tsar Alexis of Russia) kept a Moor named Savely, whom he sent to learn Russian, and the latter mastered reading, writing and singing sacred verse in Russian in just one year (and at the time, the Russian language was more difficult than it is today). Still, in the 17th century, Moors of the court were educated as a sort of amusement. It was Alexei Mikhailovich’s son, Peter the Great, who gave the Moors, as well as people of other nationalities, a very real opportunity to advance and make a career in Russia.

If there is anything in which Abram Gannibal was the first among black people in Russia, it was his career. Initially, before 1714, he was mentioned alongside court jesters, but soon afterwards, Tsar Peter must have discerned the young man’s abilities. He started to entrust him with various tasks and then sent him to study engineering in France. In later years, Gannibal taught Russians mathematics and engineering, and under Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, he was put in charge of all engineering in Russia.

Without a doubt, Gannibal was an outstanding individual – by the end of his life, he had become a general and the father of a large family (above, you can see a portrait of his son Ivan), and he was the first person in Russia to start growing potatoes on his estate.

The daily uniform of the Moors of the Imperial Court

State HermitageBy the mid-18th century, there were already quite a few black people with positions at the court: Catherine I had six Moors (they usually escorted her when she climbed out of her carriage); at the court of Anna Ioannovna there were four; while black couriers, black stokers and black musicians were to be found during the time of Elizabeth Petrovna. Moors would attend to Elizabeth when she went out hunting, her favorite pastime.

Under Catherine II, when the number of Moors appointed to the court reached two dozen, a special court position was instituted: ‘Moor of the Imperial Court’. At first, holders of this position were referred to as “Araps”, but in the 19th century it became customary to use the spelling “Arabs”, although it is unlikely that any ethnic Arabs were among them. Men as tall as possible and with the blackest possible skin were selected for the job. On assuming office, they had to adopt Christianity (either Orthodox or Catholic was allowed).

'The Empress Elizabeth of Russia on Horseback, Attended by a Page,' 1743, by Georg Christoph Grooth (1716-1749)

State Russian MuseumMoors attended the royal household on its travels, and their main duty was to open doors for the monarch at official ceremonies. And the Moors of the Imperial Court had the most sumptuous uniforms at court. According to Professor Igor Zimin, “at the end of the 19th century, under Alexander III, the ceremonial court uniforms of the Moors were the most expensive among all the court servants, and cost the treasury 543 rubles.” Only the uniform of a chamber fourrier, who was in charge of all the servants (408 rubles), and of a chamber Cossack (bodyguard) of His Majesty (418 rubles), were close to this in cost. In comparison, an ordinary man’s suit cost 10-15 rubles at the time. And the wages of the Moors of the Imperial Court ranged from 600 rubles (Junior Moor) to 800 rubles (Senior Moor) a year.

“Senior” and “junior” referred only to grades within the same rank. In the 19th century, black children - “little Araps” - were no longer kept at the court; people who came to serve as Moors of the Imperial Court were all adults. When John Quincy Adams arrived in St. Petersburg in October 1809 as the United States Minister to Russia, the first black Americans appeared at the Imperial Court. Among them was Nero Prince, one of the founders of the African Masonic Lodge in America. His wife Nancy Prince came with him. The family of the Moor of the Imperial Court had a comfortable lifestyle and even had servants.

'Anna Ioannovna with a Moorish Boy,' bronze statue, 1741, by Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli

State Russian MuseumNancy left a brief description of her visit and Russian customs. She witnessed many celebrations and ceremonies at the Imperial Court, and saw the 1824 flood in St. Petersburg and the 1825 Decembrist revolt. She surprised Russians with her refusal to dance at parties, believing it was a sin for a Christian. No matter how hard the Russians tried to persuade her, Nancy remained adamant. In 1833, she went back to America, as she found the St. Petersburg climate too harsh. In 1836, her husband followed her, having served at the Russian Imperial Court for almost 20 years.

'Ante-Room in the Imperial Palace at Tsarskoye Selo,' 1865, by Mihály Zichy (1827-1906)

State HermitageIn the Winter Palace, the Moors appointed to the court were usually on duty in the Arabian Hall. Their daily routine was not onerous - ceremonial occasions on which they had to open doors did not happen that often. Sometimes they were asked to escort palace guests to the apartments of the emperor.

During the reign of Alexander II, the Moors had another permanent duty - to prepare a hookah pipe for the emperor. Alexander had digestive problems and smoking helped him with this malaise. Besides, the emperor just enjoyed smoking and valued the Moors at court for the skill with which they mixed his tobacco for him.

'The Moorish Hall, the Winter Palace,' by Konstantin Ukhtomsky

State HermitageAnother traditional duty the Moors carried out was placing presents under the Christmas tree in the Winter Palace: The Moors were intended to symbolize the kings from the east, the Magi, who brought gifts at Christmas.

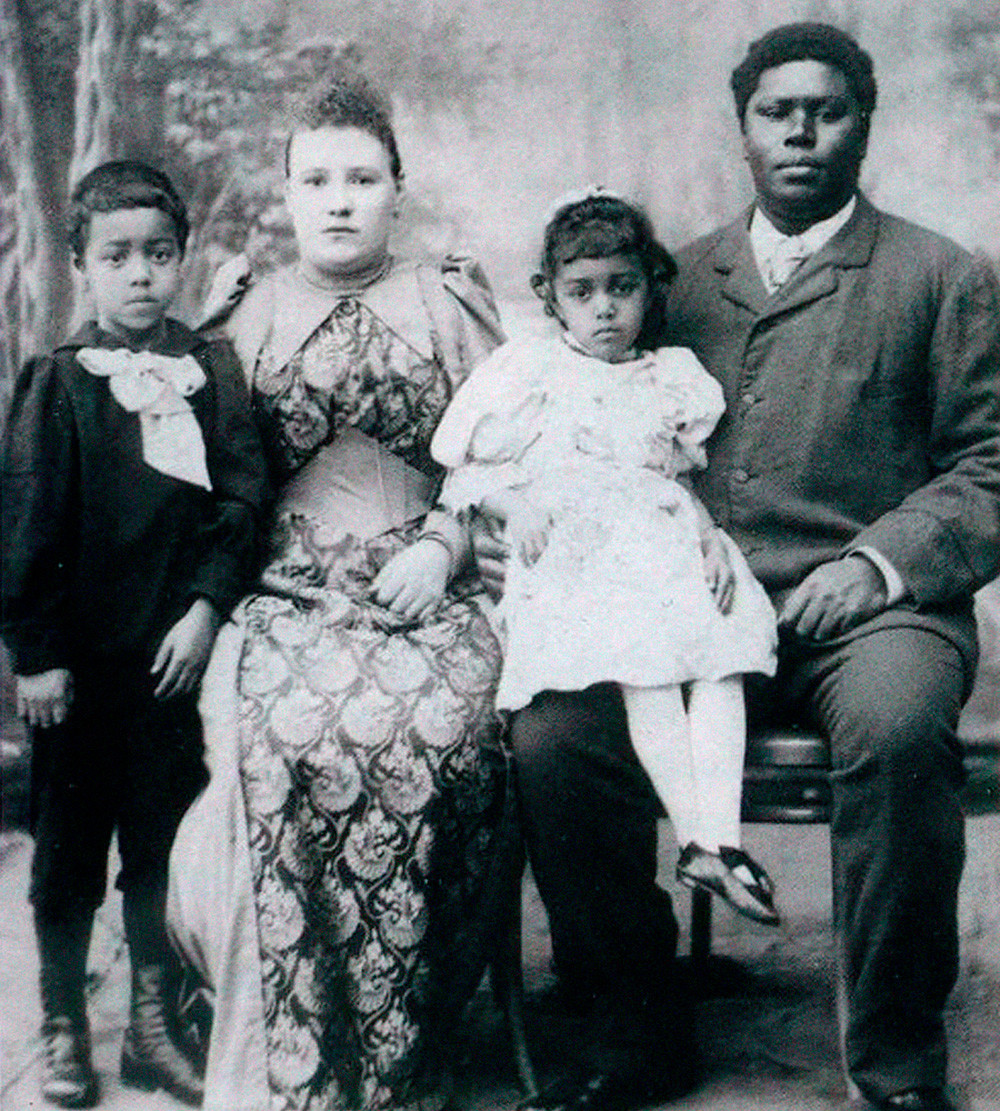

George Maria (1858-1916), one of the Moors of the Imperial court, with his Russian wife and children.

Archive photoAt the beginning of the 20th century, spending on the Moors in attendance at court was reduced, and only four remained on permanent duty. The descendants of the Moors of the Imperial Court, who often took Russian wives, still live in St. Petersburg.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox