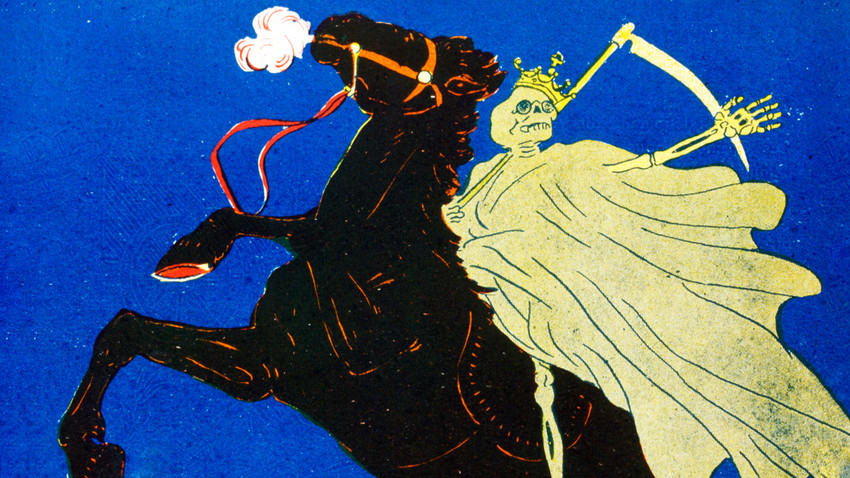

French satirical Illustration, depicting the threat of Cholera in Russia

Getty ImagesDuring the first plague epidemic in Russia in 1654, quarantine measures were already useless by the time their necessity became apparent. That epidemic was devastating, killing about 700,000 people.

By the second half of the 18th century, public awareness about mass diseases had considerably matured. In 1768, Catherine the Great vaccinated herself against smallpox, one of the most widely-spread infectious diseases of the era, and insisted that all her courtiers and officials did so too. Nevertheless, three years later it was plague, not smallpox that attacked Russia.

Plague Riot in Moscow in 1771, a 1930s watercolor by E. Lissner

Public domainIn 1771, soldiers returning from the Ottoman War brought the plague to Moscow. Neglect of safety measures meant the plague spread very fast. By July 1771, a thousand people a day were dying in Moscow. The authorities, including the governor, fled the city in fear, and riots started.

Corpses were left lying in streets and houses – the authorities lacked the sanitary staff to pick them up and bury them – so the work was performed by convicts, who wore protective clothes, but died off in large numbers anyway.

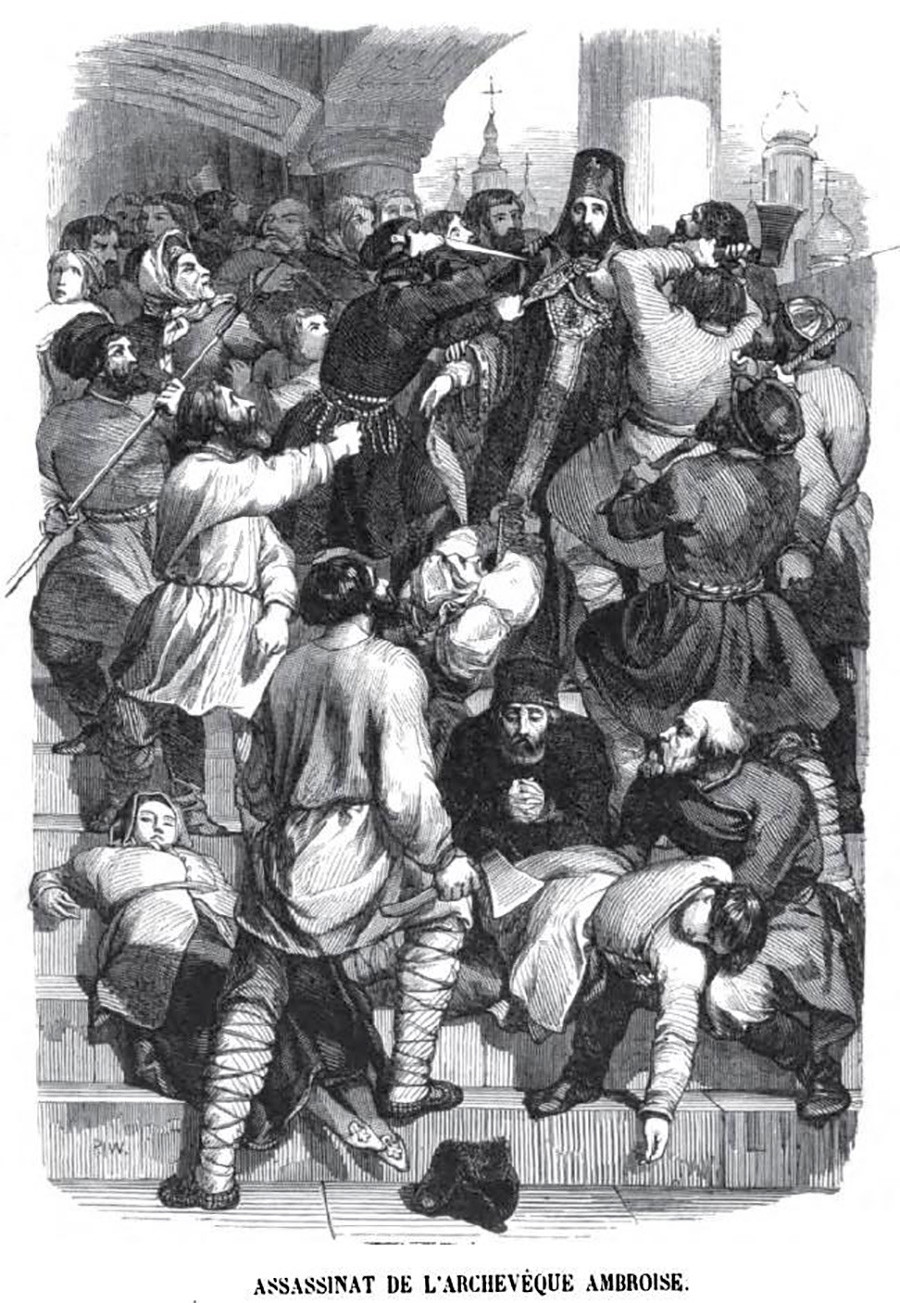

Among the panic, rumors spread that a certain icon could protect against the plague. It was placed above one of the city gates, and people flocked to climb the ladder and kiss the icon, creating a thick crowd where disease spread like wildfire. Archbishop Ambrose of Moscow (1708-1771) tried to stop the gathering, understanding that it only exacerbated the situation. His attempt to remove the icon started a riot; crowds rushed into the Kremlin and, looking for the archbishop, looted the ancient Chudov Monastery. The next day, Ambrose was captured and lynched by the crowd in the Donskoy Monastery, where he was hiding. The crowd mostly consisted of poor townsfolk and peasants.

The murder of Archbishop Ambrose, by Charles-Michel Geoffroy, 1845

Public domainCatherine the Great commissioned Pyotr Yeropkin, a wartime general, to take matters into his hands. Yeropkin was in command of some 10,000 soldiers, who entered the city and put down the riot. On 16-17 September 1771, Yeropkin attacked rioters with small arms and cannon, killing 100 or more. About 300 more were later condemned to execution and exile.

After the riot, four more regiments were placed in Moscow to ensure security, and the quarantine measures were strictly observed. Historians note, however, that the riot was not only against the quarantines but was also caused by poverty, the ongoing war with the Ottomans and dire living conditions of most people.

Nicholas I during the cholera riot in St. Petersburg on Sennaya sq.

Public domainThe cholera epidemic of the early 1830s started shortly after the 1828-1829 Russian-Turkish war - again via returning troops. The disease, first taken by people for another plague, spread in southern parts of Russia. Count Arseny Zakryevsky, then Minister of the Interior, was made responsible for safety measures, and he enforced strict quarantines on all major roads. Thousands of carts with goods were blocked by customs officials; trade stopped, and towns and villages were left without supplies. Riots started in different parts of Russia.

The St. Petersburg riot

The suddenness with which the disease overtook the body, the ugliness of its symptoms and the fact that they appeared after eating – all contributed to the rumor that cholera was some kind of poisoning. People started suspecting that some enemies were poisoning wells, and even that doctors were spreading the disease!

Doctors recommended carrying a bottle of chlorine lime, or vinegar, and to constantly rub the hands and face with it, which they themselves did to fight off the disease. But the general folk thought that these liquids were poisons. Doctors became the first victims of attacks.

On July 4th, 1831 the people tried to plunder and burn a hospital with cholera patients. Several doctors and military officers were killed. The main clashes happened on Sennaya Square, where the Izmaylovsky Royal Guard regiment was stationed. Emperor Nicholas I appeared before the public here, which helped calm the riot. However, after returning home, the Emperor burned all his clothes and spent a long time in his bath.

The Staraya Russa riot

On July 22nd, 1831, a riot started in Staraya Russa, Novgorod region. Rumors spread that the safety measures were futile, and that the government officials were actually spreading the disease, rumors that someone has poisoned the water, and general panic. In the evening, the crowd started murdering local doctors, then murdered members of the city authorities and started looting. Packs of rioteers went through the country, arresting and murdering landlords and officials.

An army battalion was sent to the city within three days to arrest the rioteers, but the skirmishes continued in the city, because several military formations located in the region started rioting, too. Some officers and generals were killed by their own troops. The riot was finally contained after a week, when Emperor Nicholas I took it under personal control; following his orders, the regiments opened fire on the rampant crowd. After a long trial, over 3,000 soldiers and peasants were executed or sent into exile.

The Sevastopol riot

Two years earlier in 1828, Sevastopol had already been quarantined because of a local epidemic – what it was exactly, plague or cholera, is now unknown, but strict measures were applied. In 1829, anybody going through the city spent two weeks in a quarantine zone, and because of the roadblocks surrounding the city, food shortages began. People complained to the authorities, but nothing happened.

A 19th-century color lithograph, with the caption "Cholera Tramples the Victor and the Vanquish'd Both," depicts a giant skeleton trampling a battlefield.

Getty ImagesIn 1830, with the outbreak of cholera, quarantine was tightened, and people were forbidden to leave their houses. One of the city districts objected against the measures, and two infantry battalions were sent to guard their quarantine zone; however, in a matter of hours the city was taken over by the rioteers, the governor Nikolay Stolypin (1781-1830) murdered by the crowd, and troops joined the revolt. The people were enraged because they thought there was no plague, and were not properly informed about the cholera outbreak. What angered them especially was the closure of churches – the majority of people didn’t understand how the disease spread, so they thought it was all some kind of a devilish hoax.

Four days later a military division entered Sevastopol and put down the riots. About 6,000 people were arrested; seven ring-leaders were executed, about 1,000 sentenced to hard labor, and more than 4,000 civilians deported to other cities. However, the measures taken proved effective, as no mass outbreak of cholera was detected in Sevastopol in the following years.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox