In the 1930s, the USSR was engaged in the rapid development of its industrial potential. Party leaders understood that, in the event of a conflict with a Western power, the consequences for the under-developed agrarian economy of “the country that brought about socialism” would be disastrous.

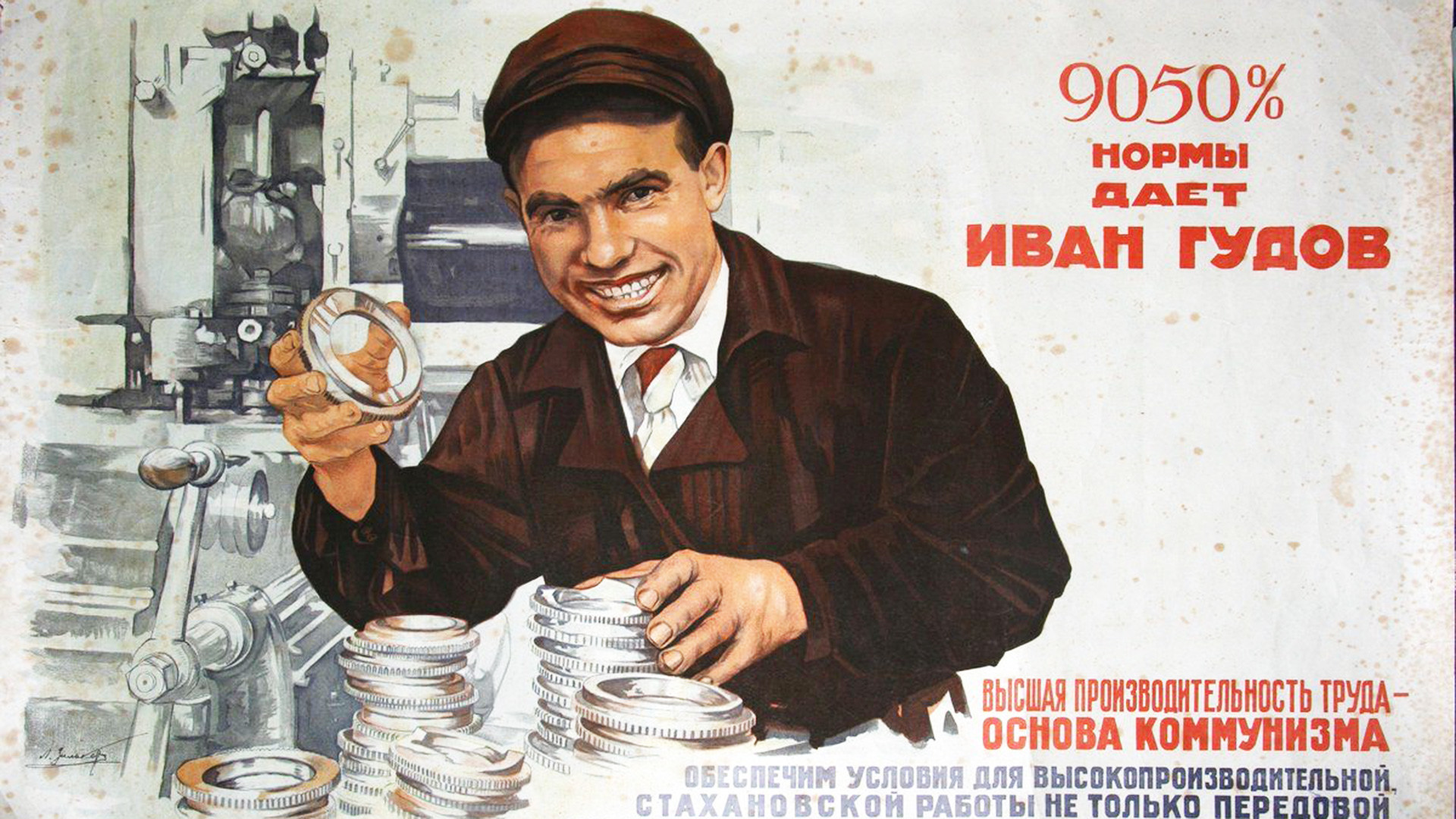

Forced industrialization demanded the mobilization of immense resources of the population, which had to constantly be motivated to work at full steam, including by holding socialist-themed competitions with awards, and creating cults of personality around the most hard-working proletarians.

One such example was made of Aleksey Stakhanov, an ordinary miner from Donbass. And the man’s subsequent popularity reached far beyond the borders of the USSR.

Aleksey Stakhanov

Evgeny Khaldey/МАММ/МDFOn the night of August 31, 1935, Stakhanov managed to complete his entire daily quota 14 times over in just one shift: instead of seven tons of coal, he extracted 102. The secret to his success was in his creative suggestion to free up one of the miners by taking him off wall support construction duties - leaving it to junior workers - and instead, have him on coal loading.

Stakhanov was God’s gift to the Soviet government. They didn’t even have to engage in a puff campaign - their ‘hero’ was right there doing their job for them. The proletarian had soon become a national treasure.

Beating his own record several times, Aleksei Stakhanov left the mines for good, swapping hard labor for propaganda work at management level. His popularity spanned so far beyond the Soviet Union that, in December 1935, he even made it onto the cover of ‘Time’ magazine.

Stakhanov’s name turned into a brand, one the country referred to as ‘the Stakhanov movement’ (or “Stakhanovschina” in Russian).

The motivation behind the PR campaign was of course to bolster productivity nationwide, introducing various innovative practices into the work process, making it more effective and disciplined.

And, oh, did the number of “national heroes” soar from there! Steel workers, millers, harvester drivers, tailors, even shoe repairmen - all were setting national records, performing at 200 to 400 percent of their daily quotas.

But it wasn’t just about building a bright Soviet future for these hard-working people. For every record set, they would get a hefty bonus. In fact, that’s how Stakhanov earned half his monthly pay during that legendary shift.

‘Stakhanovschina’ began infecting the foreign proletariat as well. Spanish communist, Enrique Lister - the only person to become general of three armies (Spanish, Soviet and Yugoslavian) in the 20th century, studied in Moscow in the 1930s. He worked on the construction of the Moscow Metro. “I was awarded the title of ‘udarnik’ in my first month, having completed 132 percent of the monthly plan. And I never dipped below it - only increased it in the following months,” he recalls in ‘Our War’ - his memoirs, published in Paris in 1966.

One may rightfully wonder - what could possibly go wrong in a system based on socialist competition for records’ sake? But the Stakhanov movement had its faults.

This fanatical approach to factory labor often resulted in broken, overworked machinery - not to mention the dwindling quality of the products. Meanwhile, daily quotas shot up, resulting in everyone having to work more for the same wages - including those that weren’t planning on conquering any Everests.

Furthermore, management would unjustly forget to fulfil its duties toward those ‘Stakhanov men’ who continued to be responsible for the continued setting of records by the group. Such a fate befell two miners, working on wall support - they served in Aleksey’s time, while the latter was busy setting his own records.

While those directly responsible for record performance continued to remain in the shadows, there were also workers willing to cheat on their record-keeping sheets, all for the glory of being promoted to ‘Stakhanov men’ and snagging bonuses.

And it’s not as if the Stakhanov work ethic was always a useful thing to have in every industry. It is sensible to assume that records in coal-mining are more crucial than fulfilling the shoe-making quota many times over - the demand just wasn’t there, and such an investment of resources into it was completely unjustified.

All in all, ‘Stakhanovschina’ did have a positive impact on productivity, as well as increasing the value of available professions. People also started to head in the right direction morally, finding heroes that they could idolize and look up to.

Stalin confirmed this at the First All-Soviet Council of Stakhanov Worker Men and Women in 1935: “Life is better now, comrades. Life is happier. And when you live a happy life, work is successful… Had we been living poorly, shabbily, unhappily, we would have no Stakhanov movement to speak of.”

The word “Stakhanovets” had become so entrenched in the Russian language that it survived even the dissolution of the Soviet Union. To this day, we praise in this way those who are willing and able to work for two, reaching new performance heights.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox