Vladimir Ulyanov (‘Lenin’ is a pseudonym) was born on April 22, 1870, to a middle-class family. His father Ilya worked as a director of a public school. Young Vladimir received classic education, which, among other things, meant cramming in Latin and Greek for hundreds of hours: there are witness accounts that Lenin was pretty good at them.

Moreover, his grandfather on his mother’s side was a landowner and a nobleman. Later, Lenin would tell his associate Mikhail Olminsky: “In a way, I am a descendant of landowners…” For a while, until the 1890s, he had a legal life in Kazan, Samara and St. Petersburg, working as a lawyer and dressing rather sharply, in tailcoats and top-hats.

This, however, doesn’t mean Lenin wasn’t a true revolutionary. Vice versa, since his teenage years, he had an example of fighting the Russian regime: his older brother Alexander had joined a plot aimed at assassinating the tsar and was executed. Vladimir, reacting to such news, said: “No, we will walk another way. That’s not a way for us.” Instead of killing the tsar, he aimed at crushing the whole system.

In 1895, Lenin, living in St. Petersburg, was arrested and sent to exile in Siberia. By that time, he had already swallowed everything Marx, Engels and dozens of other Socialist thinkers had written on the class struggle and prospects of toppling capitalism. When Lenin ran off to Europe in 1900, he was already known as a prominent philosopher and orator.

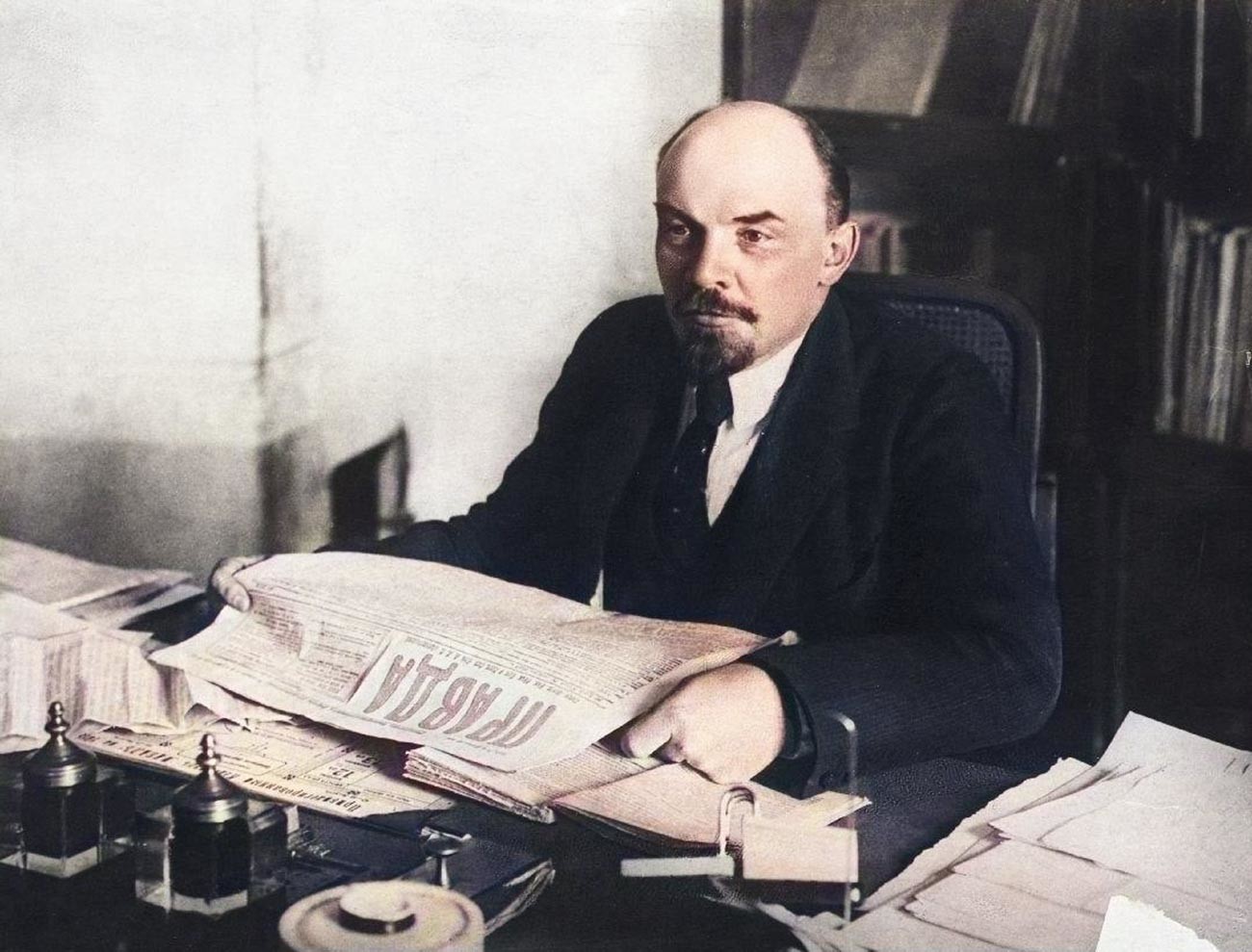

Many European socialists had no idea he could be a real son of a b*tch – at least from their perspective. Aside from “casual” Marxist business – publishing illegal newspapers Iskra and Pravda, spreading Marx’s doctrine among workers, taking part into the failed revolution of 1905 and so on, Lenin championed schisms among his fellow Marxists.

In 1902, after the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDRP), the Russian socialists fractured into two factions – Lenin led the more orthodox Bolsheviks and for 15 years did nothing to unite with the former comrades, the Mensheviks. Moreover, he used to teach his students: “If you grab a Menshevik by his throat, strangle him until he stops breathing.” Quite an emblem of Lenin’s political style. Even within the Bolsheviks, he never tolerated those who disagreed with him and would squeeze them out.

Lev Danilkin, the author of latest Lenin’s biography (2017), calls Lenin “a professional secessionist” and admits that Lenin was quite a Machiavellian type – a cynical and ruthless politician. At the same time, Danilkin writes, “Lenin managed to build an effective and reliable structure [of loyal Bolsheviks] he could use.”

In March 1917, after years of devastating WWI and economic crisis, Nicholas II was forced to abdicate – the February Revolution was won, taking down the monarchy (47-year-old Lenin had nothing to do with it). The Provisional Government was leading the country towards forming a constituent assembly. Everyone, including less hardcore Bolsheviks (Joseph Stalin, for instance), felt quite happy about democracy winning in Russia for the first time ever.

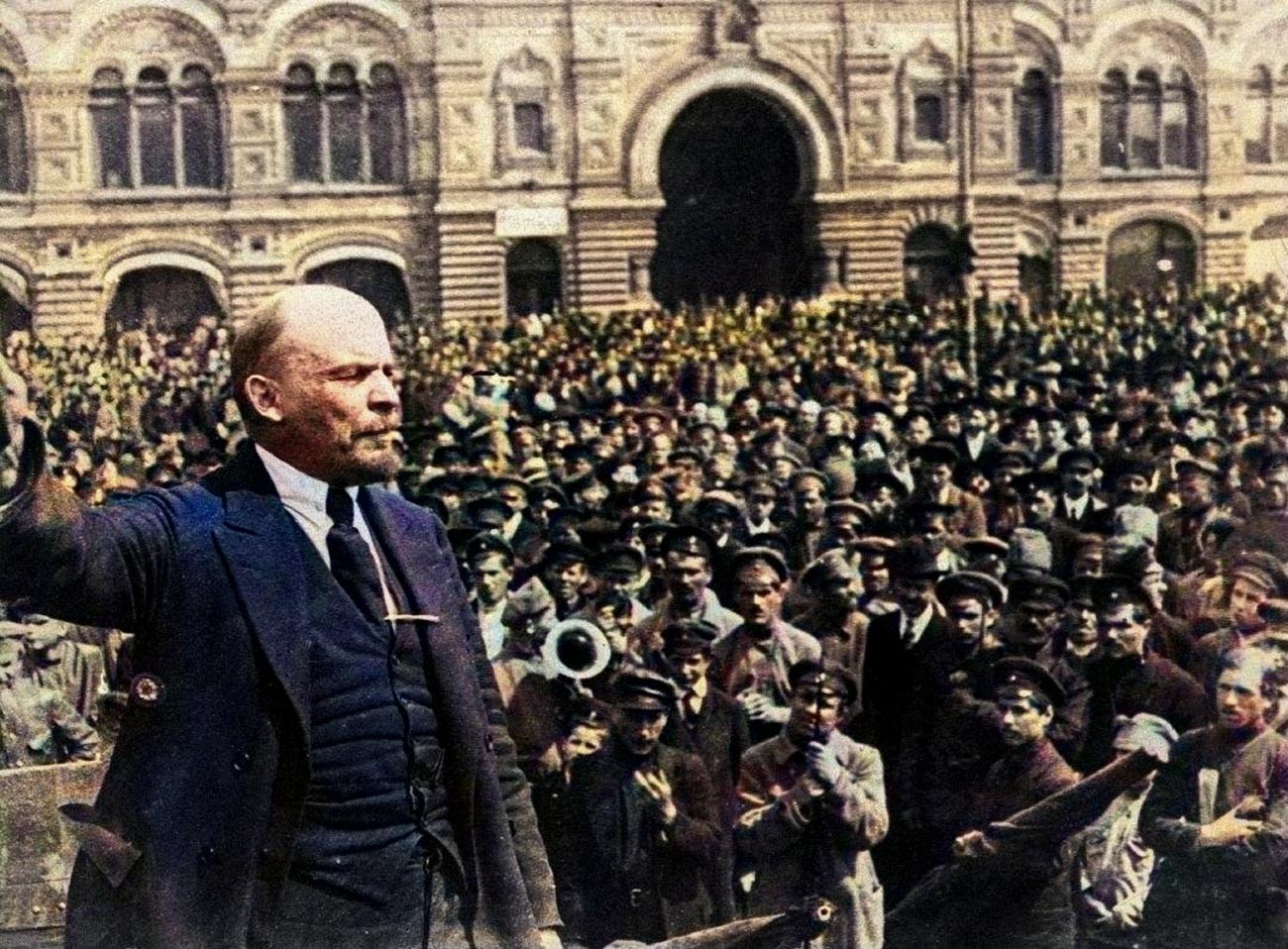

And then Lenin arrived from Switzerland in April and immediately stated in his April Theses: That’s not enough. He asserted that Russia is just “passing from the first stage of the revolution to its second stage, which must place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest peasants.” In other words, let’s have another revolution, topple the bourgeoisie and their fake democracy and build a real workers’ state.

“It was just like someone [in Russia] saying in 2014: ‘We reunified with Crimea, great, but we also need to reunify with the Moon.’ Seemed a total rubbish,” Lev Danilkin says. But it worked out. Supported by his loyal and solid party, Lenin ignited workers’ and peasants’ hearts with promises of land and peace and in November 1917 they seized power.

Led by Lenin, the Bolsheviks won the Civil War of 1917-1922 and in 1922 forged a new state on the ruins of the old empire – the USSR. But the practices of this state were very cruel. Lenin had no troubles exterminating his political opponents. The Red Terror of 1917-1922 killed, according to different estimates, from 500,000 to a million people, which made the tsarist regime, which had executed about 6,000 people during 1875-1912, pale in comparison.

“It was the elimination of whole groups (nobility, clergy, merchants, Cossacks, rural bourgeoisie) for the sake of building a new socialist society,” historian Kirill Alexandrov says. Lenin couldn’t have agreed more. “We need to encourage the energy of a large-scale, mass terror against counter-revolutionaries,” he wrote in 1918. His aim was to build a state ruled by the communist party which leads masses towards classless, ideal future (which he sincerely believed in) – and he did build it. Only the classless future failed to come.

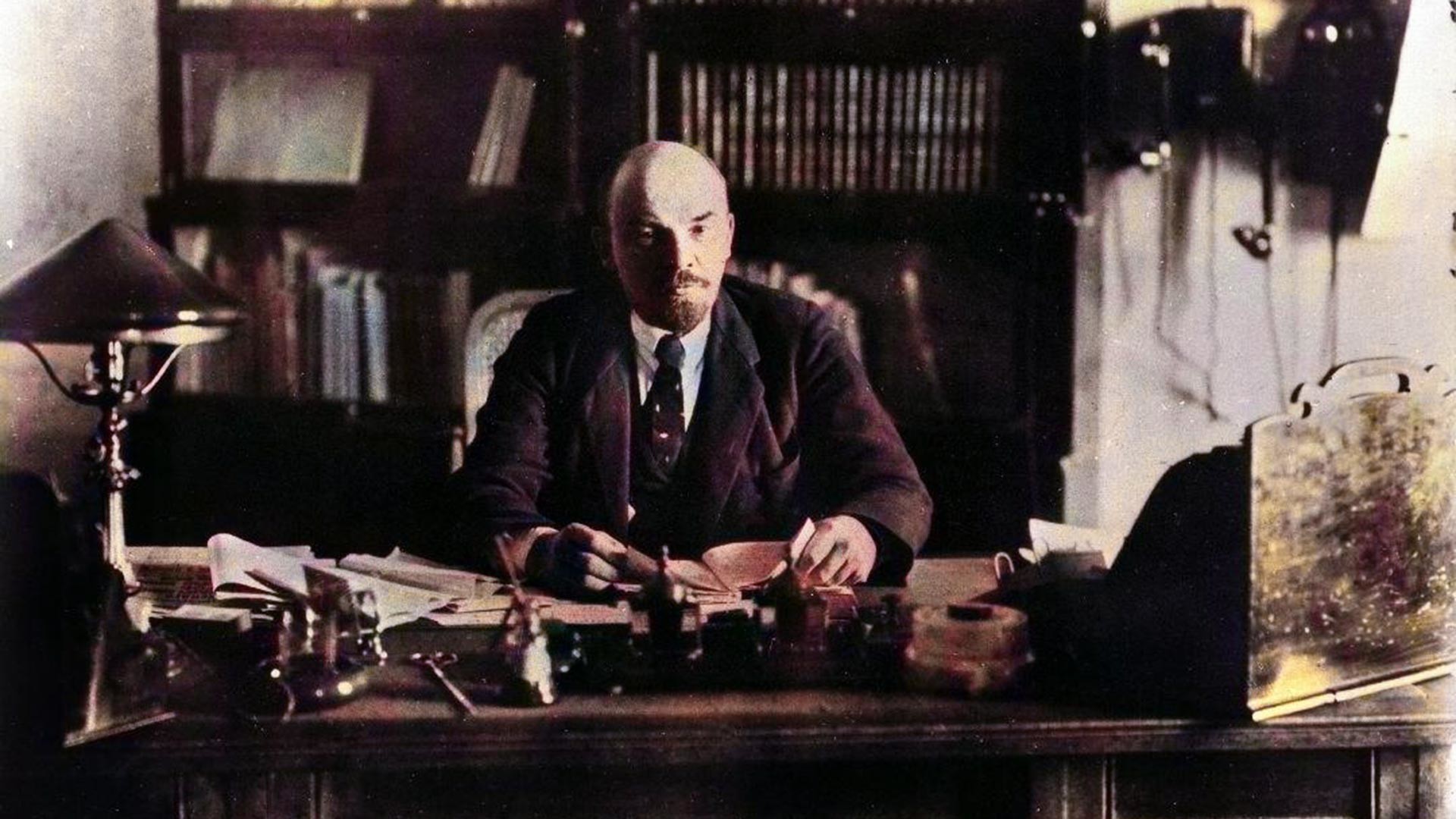

Lenin didn’t have time to triumph – instead, he put his life into the hard work of organizing the political and economic systems for the new Soviet state. Then two strokes (in 1922 and 1923) turned a charismatic, vigorous leader into a pitiful shell of a man in a wheelchair. “He couldn’t talk, but understood everything happening to him. That was horrifying. His face was full of suffering and some kind of shame,” wrote Mikhail Averbakh, one of the doctors who had taken care of him.

What destroyed the body of a man in his early 50s, remains a mystery. The official version published in 1924 says Lenin died of atherosclerosis. The other one suggests that Lenin may have died of syphilis – which was a bad thing to publish, even though in the 1920s, Russia one could get infected with this disease in everyday life, without sexual transmission, so the Soviet leadership preferred to silence it.

In any case, for the relentless Lenin, who spent his life working, fighting, writing, travelling – basically always in action – such helplessness was a terrible end. He died on January 21, 1924, to be idolized after death, put in a Mausoleum and transformed into a kind of a Communist deity for the next 60+ years. That was, perhaps, the biggest paradox of his life: a man who crushed empires and was a living revolution, turned into monuments, portraits and quotations that now can only bore most Russians.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox