A closed country behind the Iron Curtain, the USSR was full of mystery to the outside observer, which frequently led to exaggerated, often incorrect coverage. During the Cold War, both American and Soviet media exaggerated the facts, putting their own spin on the news.

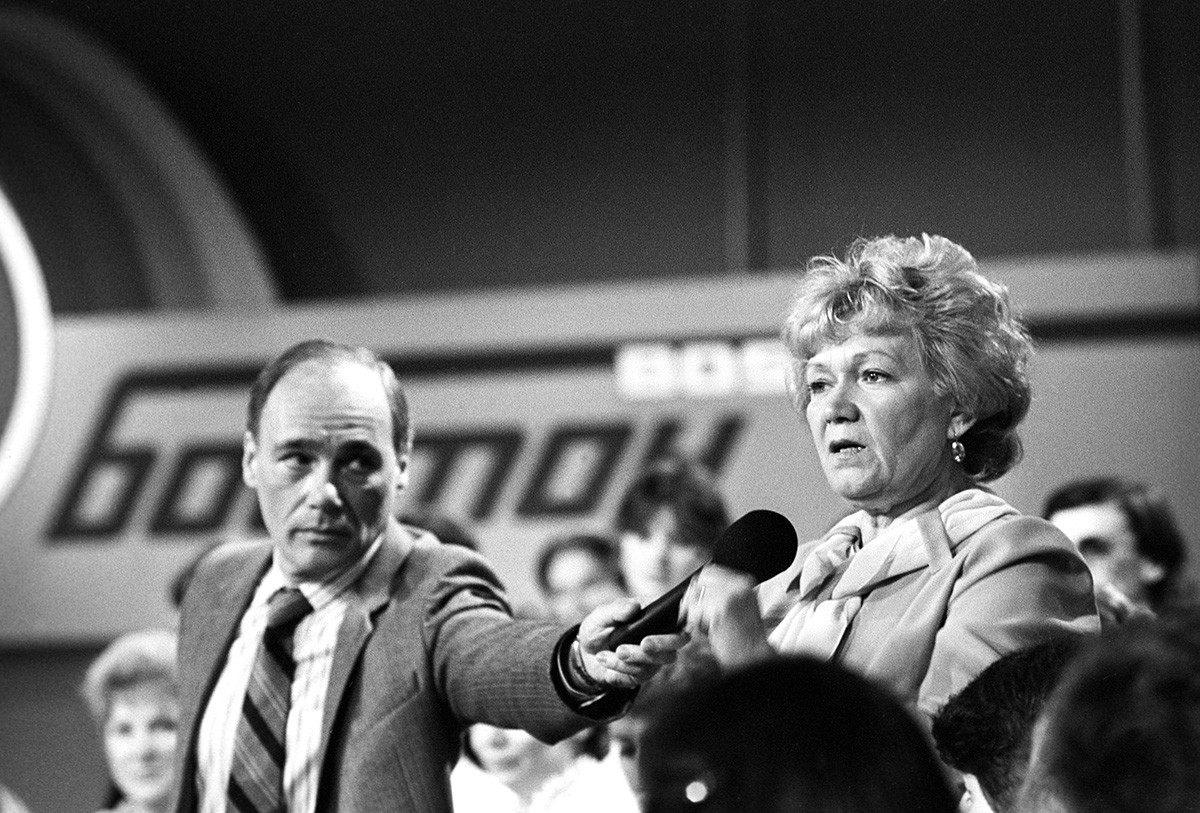

In 1986, Soviet journalist Vladimir Pozner and his American counterpart Phil Donahue arranged one of the first ever U.S.–Soviet tele-conferences between the two rival countries, broadcast live into everyone’s homes. The so-called ‘Space Bridges’ - which would become a tradition, were TV-links intended to fill the information gap and let the two peoples overcome their respective prejudices by talking to each other.

Vladimir Pozner during 'Leningrad-Boston' TV conference

Mikhail Makarenko/SputnikThe famous phrase “There is no sex in the USSR” was coined during that broadcast. Female citizens of Boston and their Leningrad interlocutors asked lots of questions, wanting to know everything about women’s lives on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

One of the questions from Boston was about Soviet advertising. An American woman said that the U.S. commercials have a lot to do with sex, and asked if there was sex in Soviet commercials. A Soviet woman, Lyudmila Ivanova, replied: “No, we don’t have sex, and we are strongly against it”. This immediately elicited a burst of laughter from the Soviet audience - but one of the women is clearly heard correcting the speaker: “We DO have sex, we just don’t have such commercials”. Vladimir Pozner himself also added that the claim was a mistake.

Later, in 2004, in an interview for "Komsomolskaya Pravda" newspaper, Ivanova claimed that her actual words were “There’s no sex in the USSR, we have love instead”, but the last part of it was drowned out by the laughter from the audience.

“Am I wrong? The word ‘sex’ was something close to obscene vocabulary. We didn’t do sex, but we made love. That’s what I meant,” she added.

The “we had love instead” version was later confirmed by the director of the Space Bridge Vladimir Mukusev. He also said that Ivanova asked him to delete this part of the recording. He remembered considering it for a while, but in the end,decided to leave this part, which united both the U.S. and Soviet audiences in laughter, giving them something humorous to connect over. It obviously caused Ivanova some distress, as Mukusev later recalled.

As a result, the phrase “We don’t have sex in the USSR” was immediately picked up and turned into a joke by both the Americans and the Soviets. When using it, the latter liked to add that kids in the USSR were born because of strong love... for the Communist Party!

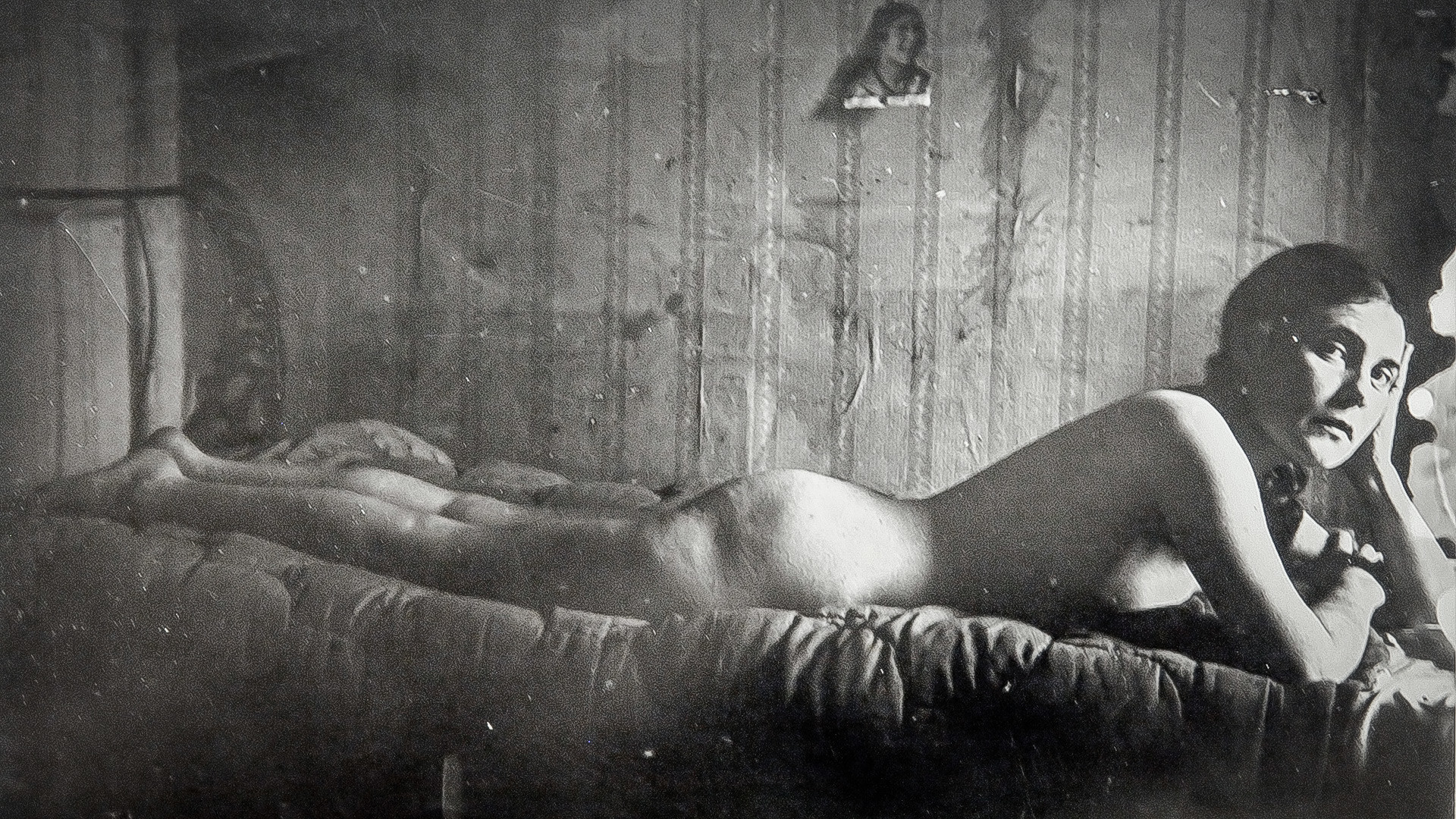

After the Revolution of 1917, there were ideas to use ‘free love’ (sex) as a tool for demographic growth, while marriage was proclaimed an evil relic of the nation’s tsarist past. So, we can indeed say that a full-blown sexual revolution was occurring in those days.

Sex symbol of the Soviet 1920s - Lilya Brik

Alexander Saverkin/TASSThe 1920s in the USSR were marked by avant-garde belief systems involving free love and open eroticism. But Soviet authorities had soon realized that the new state didn’t benefit from these moral principles, and reversed this policy, putting the nation on a strictly puritanical course. “Sexual promiscuity” began to be perceived as a relic of capitalism and, therefore, unacceptable.

Openly discussing sex had quickly become taboo in the USSR, reserved only for conversations between friends or lovers in the privacy of their homes. Moreover, there was almost no sex education in the Soviet Union from the mid 1930s and onwards (unlike in the early days of Lenin’s Bolshevik experimentalists, who battled STDs and a whole host of other issues).

A still from "Little Vera" by Vasily Pichul. Gorky Film Studio. 1988

Global Look PressHowever, in the 1980s, with the beginning of the perestroika, the Soviet media started to publish information about sex, contraception and related topics. It was only then that sex once again returned to the public sphere - as evidenced by a massive explosion in the arts, especially in late-Soviet and early Russian cinema.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox