“This monument is not about telling our history, it’s not about acknowledging it. It’s a monument, it’s a place of honor for someone who does not deserve our honor,” said Dionne Yeidikoo’aa Brady-Howard, one of the members of the Tlingit population, about the statue of Russian settler Alexander Baranov, the first chief manager of the Russian-American Company, who actually founded the city in 1799 as the Fort of St. Michael (it was later named 'Novo-Arkhangelsk').

The statue of Alexander Baranov in Sitka, Alaska

Legion MediaThe statue, donated to the city in 1989 (to mark the 190th anniversary of Sitka) by one of its families, was placed in a seaside park in Sitka. But recently, in late June 2020, members of the native Tlingit population asked the city to relocate it.

But Alexander Baranov was a far more complex man than today's Alaskans know, and certainly did not harbor the kind of ill will or genocidal intent as might be associated with a run-of-the-mill colonist.

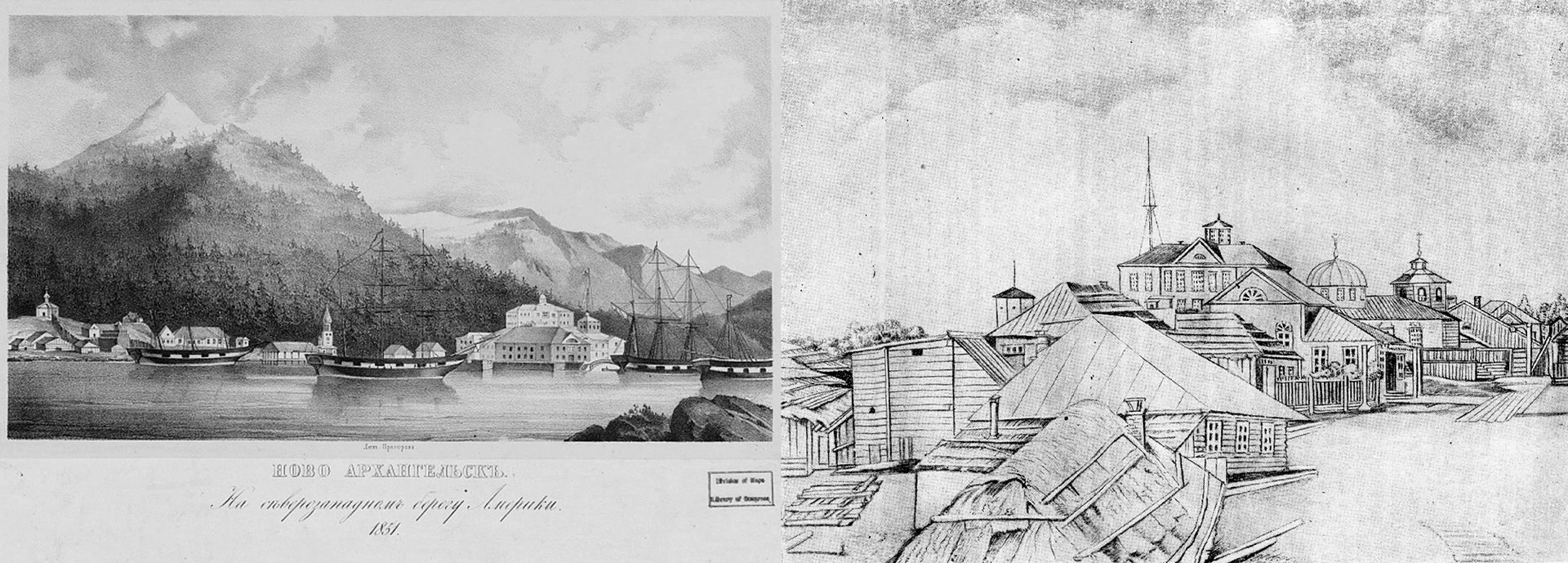

Novo Arkhangel'sk. On Northwest Coast Of America, 1851

Legion MediaWhen Alexander Baranov came to Irkutsk, Eastern Siberia, in 1780, he was 34. Born in the northern Russian town of Kargopol into a merchant’s family, Alexander had been doing business since his teens – in the Arkhangelsk Region, in Moscow and St. Petersburg. In Irkutsk, he bought property and started organizing expeditions to Alaska.

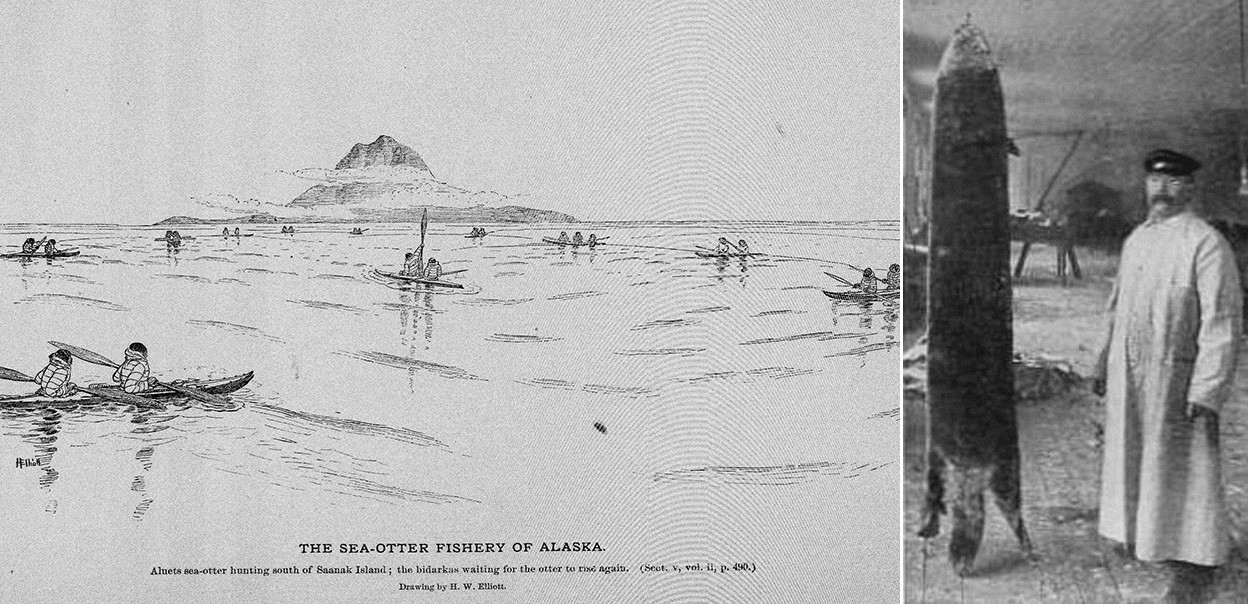

Travelers hired by Baranov sailed to the Alaskan shores, where they hunted sea otters - very abundant in those parts - for their exceptionally thick fur, a very expensive commodity in Russian-Chinese trade in the late 18th century. The bounties from this trade were exceptional – one ship could transport up to 50,000-70,000 rubles worth of fur at a time when 2,000-3,000rubles a year was considered a lavish income.

Grigory Shelekhov, a post-humous portrait by an unknown artist

M. Kocherov's collectionSoon, Baranov was approached by Grigory Shelekhov, the founder of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, which specialized in sea otter fur trading, to be the chief manager of his company, which Baranov became in 1790. The company employed the Aleut and the Alutiiq peoples of Alaska, who hunted sea otters. The fur was transported to Russia on merchant ships. But the indigenous people didn’t do it of their own free will. Shelekhov was naturally a ruthless and cruel man who would do anything to achieve his ends. To subdue the locals, he used brutal force. For instance, in the Awa'uq Massacre of 1784, Shelekhov’s 130 men, armed with guns and cannons, murdered several hundred Alutiiq people, including women and children, to ‘conquer’ the tribe’s land.

Russian officials, however, understood that Shelekhov was a maniac. "Those charged with collecting the iasak [an old Russian-Tatar word for tributes, here – sea otter fur] had often misused their powers", wrote Ivan Yakoby, the Governor-General of Irkutsk. So, no wonder, he continued, that the Alaskan people "shunned any allegiance and had attempted to take vengeance on the Russians in any way they could."

Sea-otter fishery of Alaska (L) and an Alaska black silver-tipped sea-otter (R)

Legion MediaAfter Grigory Shelekhov’s death in 1795 (the circumstances are not clear; he was just 46), his company was reorganized into The Russian-American Company, a vast enterprise that consolidated the Russian merchants’ sea otter fur trade in Alaska and the neighboring territories. The company’s initial starting capital was 700 thousand rubles, but in a year, it grew to 2,5 million rubles – the company’s trade was highly profitable, and even members of the Russian royal family became its stockholders. Alexander Baranov had become the company’s first general manager.

He called himself ‘The Pizarro of Russia,’ but he wasn’t a military man, and his exploits and achievements are far less meaningful. From 1790 onwards, Baranov controlled the construction of forts and villages in the Russian Alaska, inviting shipbuilders to construct vessels right there on Kodiak Island. Baranov controlled the sea otter fur trade, the animals were being killed in dozens of thousands. In Alaska, he married an Aleutian chief’s daughter, who bore him several children.

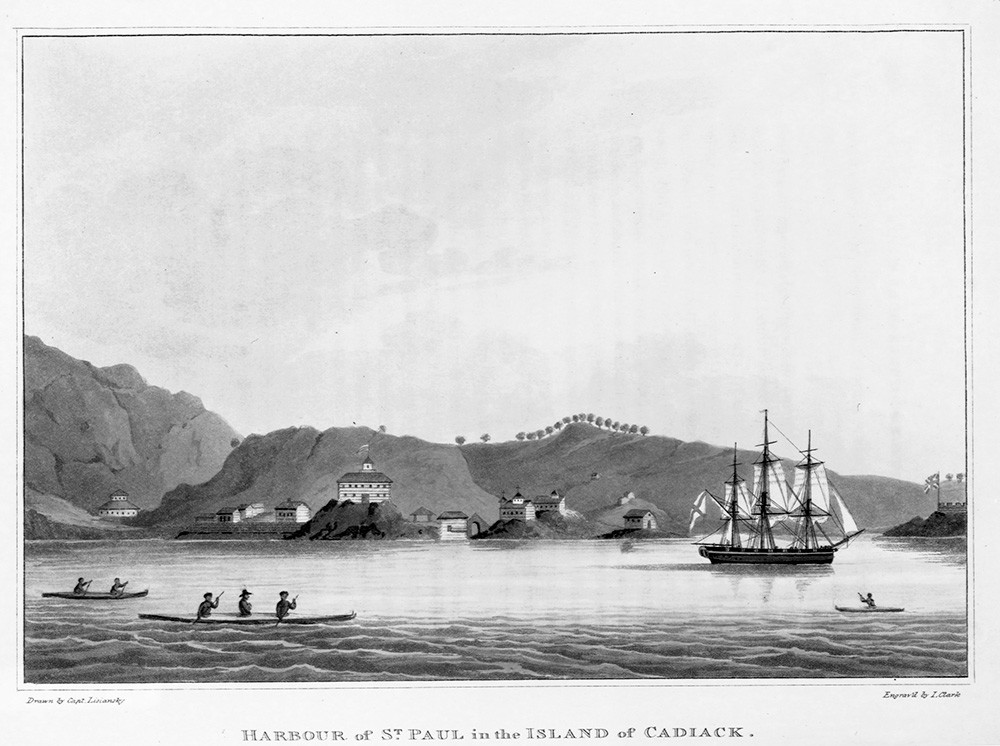

In 1799, Baranov founded what would become Sitka, naming it Fort Saint Michael. At the time, it wasn’t yet a city, only a small fortress. In 1802, the Tlingit tribes attacked the fort, killing about 20 Russians who were protecting the place, and demanding ransom for the captured Russians. Baranov was able to re-capture the fort only in 1804, using the help of Yuri Lisyansky, a naval explorer who temporarily stopped in Alaska for supplies. Baranov and Lisyansky finally succeeded after two months of fighting. Baranov was determined to establish a city here, and in a year, he ordered eight houses built in Novo-Arkhangelsk, the way Baranov referred to it. He finally made peace with the Tlingits and gave their chief a massive Russian coat of arms made of copper.

The harbor of St.Paul on the isle of Kodiak, then the capital of Russian Alaska, as seen in Urey Lisiansky's A Voyage Round the World, 1814.

Getty ImagesAlexander Baranov was a devoted and relentless colonist. He didn’t rest a day. However, fighting off the Tlingits and governing the Aleuts weren’t the only problems on his plate. For starters, Baranov had also had troubles with his own people – Russians, who tried to smuggle the otter fur out of Alaska unbeknownst to him.

Another problem had to do with frequent resupply issues. Russian ships would often crash against the rocks in the thick Alaskan fog, with valuable supplies and food being lost again and again. Baranov would have to send captain Ivan Kuskov to California, where Fort Ross was founded in what is now Bodega Bay. The former Russian establishment served as a ‘breadbasket’ for Alaska because the Californian lands were abundant with crops and cattle.

Sitka, Baronof Island, Alaska, United States, North America

Getty ImagesAs early as 1798, Baranov started asking for discharge. Nikolay Rezanov, the director of the Russian-American company, described firsthand the modest circumstances of Baranov’s life.

“None of us are particularly spread out here, but our ‘conqueror’ lives in some wooden yurt, so damp inside that mold has to be removed every day, to say nothing of the heavy local rains, which make the place resemble a dripping sieve. A remarkable man! He cares only for others’ convenient existence while disregarding his own needs to the extent that I once found his own bed floating in a puddle of water, and asked him if a section of the hut had been torn off by the strong wind, to which he casually responded: ‘No, I guess the water must have oozed inside from the town square,’ and continued his daily governance routines.”

Twice, the Russian-American company sent new chief managers to replace Baranov. In 1811, the first of them, Ivan Koch, didn’t make it, dying in Petropavlovsk en route to Alaska. Immediately, another replacement officer, Tertiy Bornovolokov, was commissioned, but he died in 1813 in a ship crash just 10 hours’ sail from Novo-Arkhangelsk.

Only in 1817 was Baranov replaced as governor of Russian America. (Here, we must underline that his position of 'governor' wasn't a military one, but a civil position inside the Russian-American company.) Baranov was replaced by a man named Ludwig von Hagemeister. After inspection, Hagemeister found no evidence of any malfeasance by Baranov. The only thing that didn’t match the records was rum: the Alaskan Russians surely drank more of it than the journal said. Alexander Baranov, indeed, governed Russian Alaska selflessly. During his time, the Russian-American Company’s capital grew to 4,5 million rubles, and he was leaving Alaska almost in rags. The most expensive thing he got was the Russian Order of St. Anna, 2nd class, that he earned in 1807 “for repelling the attacks of the Tlingit natives.”

In November 1818, Baranov left Alaska for Russia on the ‘Suvorov’. In March, the ship made a short stop on the island of Java, where Baranov, 71 at the time, fell ill. On April 16th, 1818, Alexander Baranov died onboard the ship and was buried at sea, never reaching his homeland.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox