Ivan Aivazovsky. Brig "Mercury" Attacked by Two Turkish Ships.

Ivan Aivazovsky/Feodosia National Gallery I. K. AivazovskyNot many a sailor would have the guts to go into battle with 20 cannons versus the enemy’s 184. However, that is exactly what the Mercury did.

The uneven battle took place on May 26, 1829, near the Bosphorus, in the course of another Russian-Turkish war. Three Russian reconnaissance ships were ambushed by a Turkish fleet of 14 vessels.

The ‘Shtandart’ frigate and ‘Orfey’ brig managed to make it out. The Mercury, however, wasn’t quite so lucky. Two of Turkey’s line ships managed to catch upto it: the 110-cannon ‘Selime’ and the 74-cannon ‘Real-Bey’.

The Mercury was not outfitted for a full-on battle. The small brig armed with 20 cannons was suited primarily for surveillance and convoy duties. Nevertheless, captain-lieutenant Aleksandr Kazarsky reported to admiral Aleksey Greyg: “We have unanimously agreed to factor in every last possible resort.” By which he of course meant the prospect of sinking the ship, lest it fall into enemy hands.

Russian navy men aimed deliberately at the enemy ships’ masts and riggings, managing as a result to render the vessels immobile. After several hours of heavy fighting, resulting in four dead and six wounded men, 22 holes in the ship and 133 in the sails, the Mercury somehow managed to escape enemy pursuit and set a course for Bulgaria.

Even the Turkish sounded off on the bravery of the Russians that day: “Should great feats of bravery be discovered in times past and present, they are surely overshadowed by this act, and the name of the hero must forever be inscribed in gold lettering in the hall of fame: that name is captain-lieutenant Kazarsky, and the brig - ‘Mercury’,” Real-Bey’s navigator later wrote.

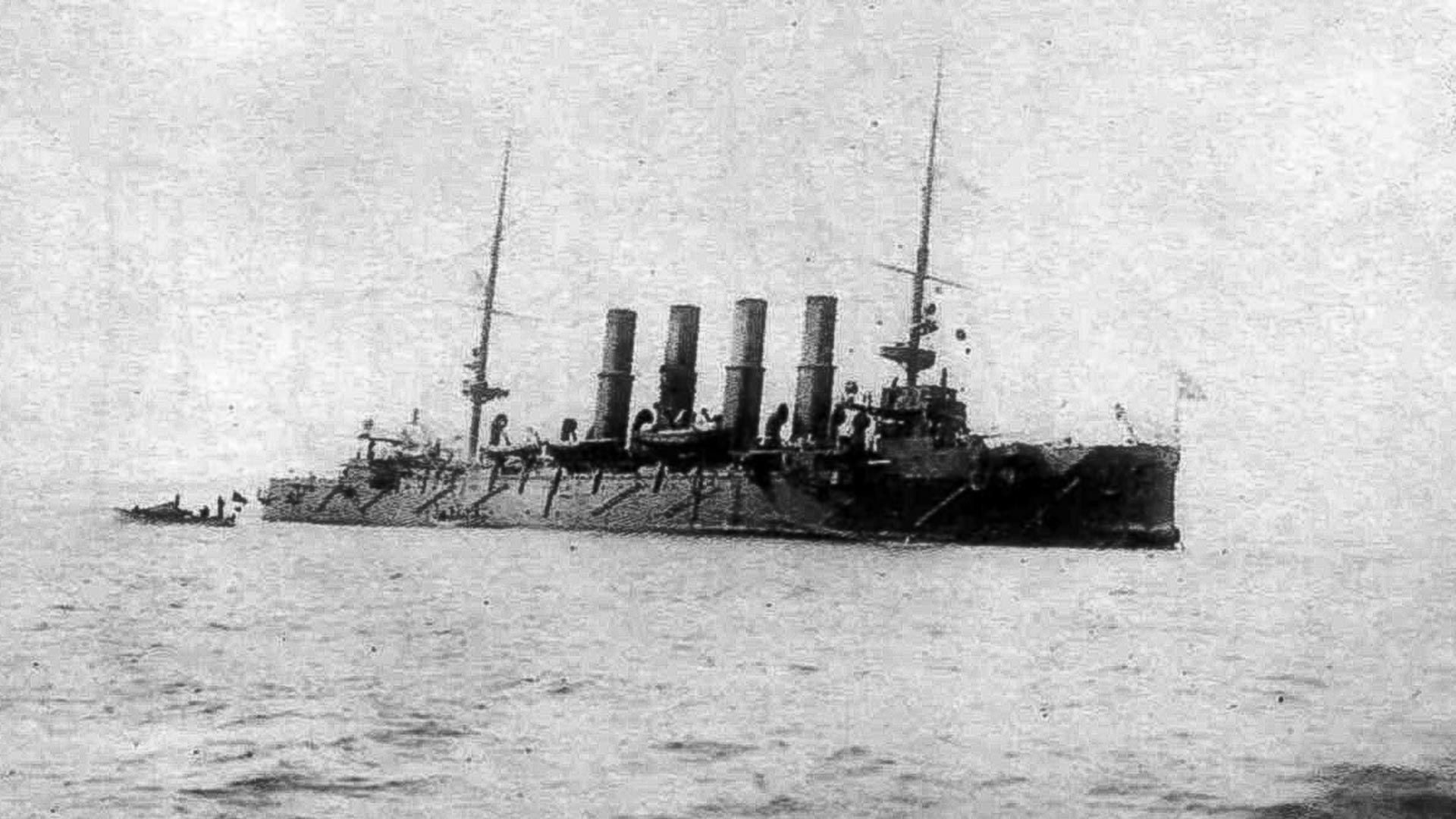

‘Varyag’ armored cruiser after the battle.

Public DomainThe Russo-Japanese War turned into a major catastrophe for Russia, but it still presented plenty of occasions for Russian sailors to display their heroism.

At the very beginning of the conflict, on February 9, 1904, a squadron of 14 Japanese cruisers and bombers blocked the neutral Korean port of Chemulpo (present-day Incheon), which harbored the Russian armored cruiser ‘Varyag’ (“The Varangian”) and the ‘Koreets’ (“The Korean”) gunboat.

When admiral Uryu Sotokichi of the Japanese Imperial Navy presented Varyag captain Vsevolod Rudnev with an ultimatum that involved a surrender, the latter instead decided to make a break for Russia’s base of Port Arthur (present-day Dalian, China), and in the event of failure, to blow up both vessels.

The crew of neutral ships in Chemulpo Bay all lined up on deck with screams of “Hoorah!” to show respect to Russian sailors departing for battle. French Captain Victor Sénès then spoke the words “We salute these heroes, heading so proudly into certain death.”

The unequal battle against the Japanese lasted for three hours. After the Varyag received serious damage and lost 40 men, the decision was made to evacuate the crews to nearby neutral ships and sink the Russian ones.

Despite captain Rudnev’s subsequent damage report, including Japanese losses, neither the Japanese nor the neutrals ever confirmed it. Despite that, the enemy was so taken with Rudnev’s and the Varyag sailors’ valor on that day that, after the war, in 1907, Emperor Meiji acknowledged this by presenting Rudnev with the Order of the Rising Sun 2nd Class. The Russian captain accepted the honor, but never wore the medal.

But the Varyag’s tale doesn’t end with the sinking at the Battle of Chemulpo. In August 1905 it was raised from the ocean, refurbished and entered into the Japanese Imperial Fleet as a ‘Soya’ 2nd class cruiser. Russia bought the ship during World War I and the ship entered Russian ranks to fight another day. After several years of service, in 1925, the Varyag ran into some cliffs off the coast of Ireland. It was partially taken apart, then blown up.

Russian sailors in Messina.

Public DomainSea battles weren’t the only place the heroism of the Russian Navy was put to good use. There was a particularly memorable occasion in peacetime, after the devastating earthquake in the Strait of Messina, Italy - the strongest in recent European history.

The magnitude 7.5 earthquake struck on December 28, 1908 in the Strait of Messina, between Sicily and mainland Italy. As a result, about 20 settlements were destroyed, with fatalities ranging from 90,000 to 120,000 people.

Several countries answered the appeal for assistance. The first to show up was the Russian Baltic Fleet, which happened to be on military drills in the region. The sailors witnessed a frightful sight: the city of Messina was almost entirely destroyed, with thousands trapped under the rubble.

The rescue mission lasted a day and night, with the assistance of projector lights from ships. Locals reported that the Russian sailors sometimes refused sleep, food or rest. Several died in building collapses while trying to sift through the debris.

Russian military doctors also set up field hospitals to aid the victims. The severely wounded were transported aboard ships to Naples and Syracuse.

Looters were another problem, leading to the need for martial law. “Full of confidence, the thugs weren’t afraid of strangers they had never met, and proceeded to loot and set fires in broad daylight,” the St. Petersburg newspaper ‘Rech’ wrote on December 30, 1908. “Without waiting for the appropriate orders, the sailors began to scoop up the hoodlums and clear the streets of them… [looters] were shot on the spot.”

Russian sailors were stationed in Messina for five days, managing to save more than 1,300 people. All were presented with various honors, with some even having streets named after them. A monument was also planned at the time, but did not materialize, for various reasons, until more than a century later, in 2012.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox