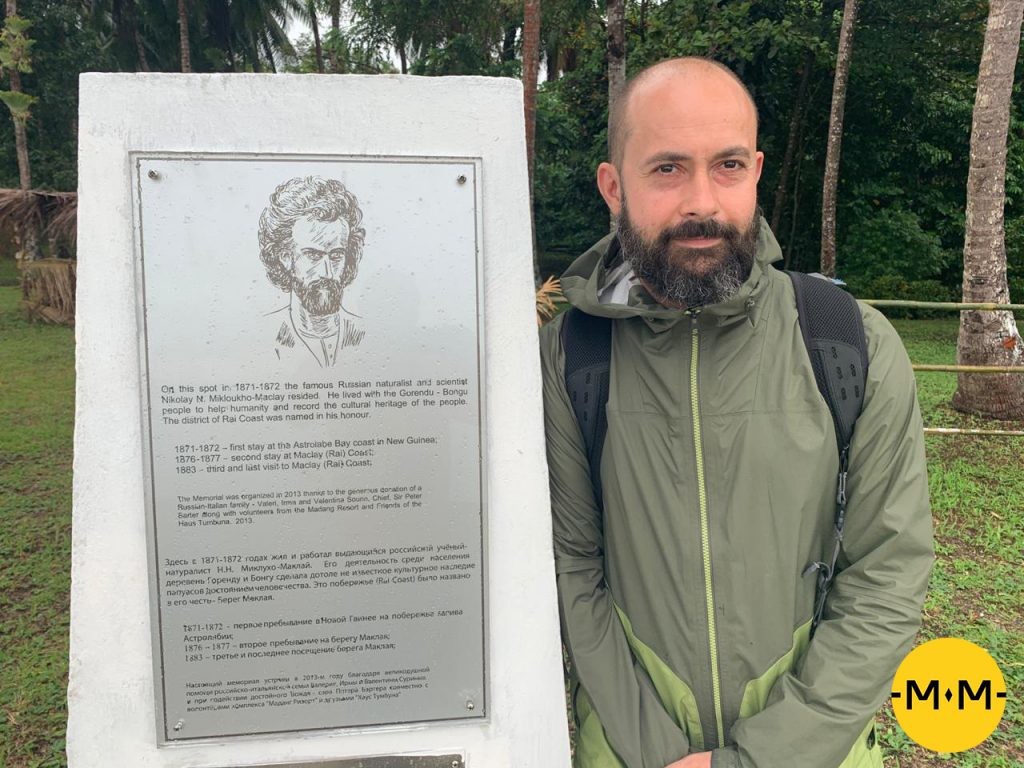

A Russian flag flew over one of the villages of Papua New Guinea in 2019. The local aboriginals were greeting an expedition led by the great-nephew - and namesake - of the famed anthropologist Nikolay Mikluho-Maklay. 150 years ago, his great-great-grand uncle’s hut had stood where the flag was flying. “They remember Russia really well here, and the ‘man from the moon’ - a moniker given to Maklai for his skin color,” Nikolay Miklukho-Maklai Jr. says. After his 2019 visit, the village was also subsequently renamed in his ancestor’s honor.

Together with colleagues from Moscow and St. Petersburg, Miklukho-Maklai Jr., a leading expert at the Institute of Oriental Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAN), created a detailed chart with the names and coordinates of all the places in Oceania discovered by Russian explorers in 19-21 centuries.

During field trips in 2017 and 2019, with the aid of Australian archives, the researchers managed to establish the existence of 71 toponyms, of which eight had prior, original names. The rest were given new names.

The Russian scientists wish to preserve the memory of their forebears’ discoveries, at least on Russian maps.

READ MORE: 150 years on, another Miklouho-Maclay is off to meet the Papuans

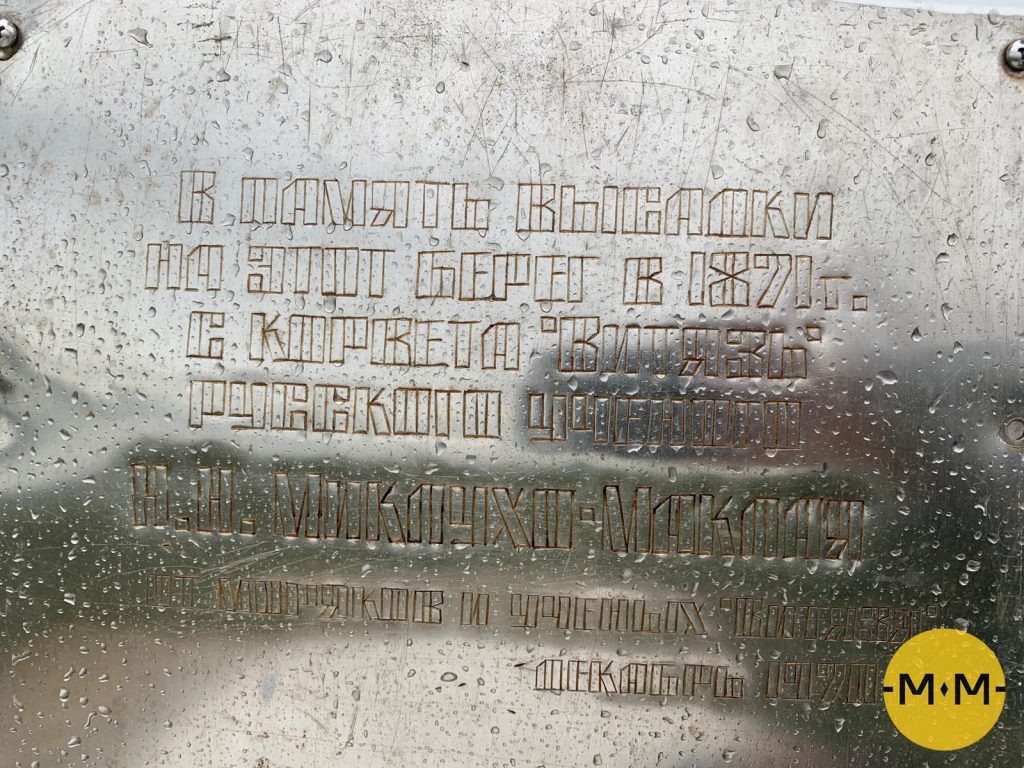

The Maklai Shore - the north-eastern shore of the island of New Guinea, was renamed Rai Coast, a title borrowed from a nearby village in the early 20th century, at the time of German colonization. A similar fate befell some 50 other locations, originally named by Miklukho-Maklai and Russian sailors. There were also subsequent changes made by Australians.

Here is a list of locations in Oceania that carry their Russian names on international maps to this day.

Russia and Oceania possess a strong historical bond and a relationship that has lasted for more than two centuries. 19th century Russian circumnavigators, Soviet expeditions of the 1930s and 1970s, followed by Russian ones in 2017 and 2019 have all contributed greatly to the study of the regional aboriginal peoples and the advancement of their way of life.

The residents of several villages pass down stories of Miklukho-Maklai’s contributions in the form of metal tools, as well as some Russian words that ended up in the local language - Bongu. Words like “topor” (“axe”), “kukuruza” (“corn”) and “arbuz” (“watermelon”).

While carrying out his anthropological research in Australia, Milkukho-Maklai founded the first biological lab in the Southern Hemisphere. Aside from his research trips, the remainder of the Russians’ travels to Oceania in the 19th century were more or less transit stops. The sailors demonstrated to locals the Russian flag, refilled on food and fuel, which they swapped for metal weapons, and collected information on the settlement of Australia by English colonists. Using that knowledge, captain Ivan Krusenstern in 1823 published the ‘Atlas of the Southern Sea’ - one of the only ones so accurate that it was used by sailors the world over to navigate the Southern Pacific until the start of the 20th century.

Today, the memory of Russian exploits in Oceania remains in part thanks to the family foundation, run by Nikolai Miklukho-Maklai Jr.

“The Russians were doing research - not conquest,” claims Sofya Pale, lead specialist of the Center for Asia-Picifc Studies at RAN’s Institute of Oriental Studies. “Discovering another unknown island, the captains would travel around it to map the coastline and put it on the map. While there, they would either talk to the locals and find out the name, or, if the island was uninhabited, make up one of their own and lay in the coordinates for its newfound location into their journal,” she adds. “This information would then be sent to Russia’s maritime department, where it would be classified. The English, meanwhile, were a naval superpower, and anchored their ships in every port they happened upon.”

Archives at the State Library of New South Wales, Australia, together with the sailors’ journal entries, enabled researchers to discover a number of the lost names. A chart was created, listing in alphabetical order the Russian and current names, together with the coordinates, circumstances of discovery and current political and administrative status. The resulting research was published in the book ‘Russia and Oceania’, and can be viewed in this short film.

The collated data is also being used in the creation of a new world atlas, commissioned by President Vladimir Putin in 2018. According to the Russian leader, the current information has sustained a number of edits, many of them regarding old Russian toponyms: “We’re not about to force our views on others… but to abstain from reacting at a blatant twisting of historical and, in this case, geographical truths, is not within our rights,” Putin said in April 2018 at a meeting of the board of trustees of the Russian Geographical Society, which he chairs. The naming project was assigned to The Federal Service for State Registration, Cadastre and Cartography, the Ministry of Defense and the Russian Geographical Society.

“Each country has the right to assign such names as it seems fit,” Miklukho-Maklai Jr. says. “Renaming objects or listing alternate names in brackets for posterity is something we can only do on our own maps.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox