Peter the Great knew how to use the plant for his material, not spiritual, needs.

Getty Images, Russia BeyondRussia before the 20th century was mostly an agricultural country, and the decisive majority of its exports were raw materials. Hemp, a plant of the genus cannabis sativa, was one of the biggest factors in Russia’s exports. The strains that were grown in Central Russia were low on tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive component of the plant, so Russians didn’t get high on it (there are no records of a massive recreational use), but the state surely got rich with it. Moreover, Russia actually supplied its biggest naval enemy, Great Britain, with hemp that was used to make rigging for the British fleet…

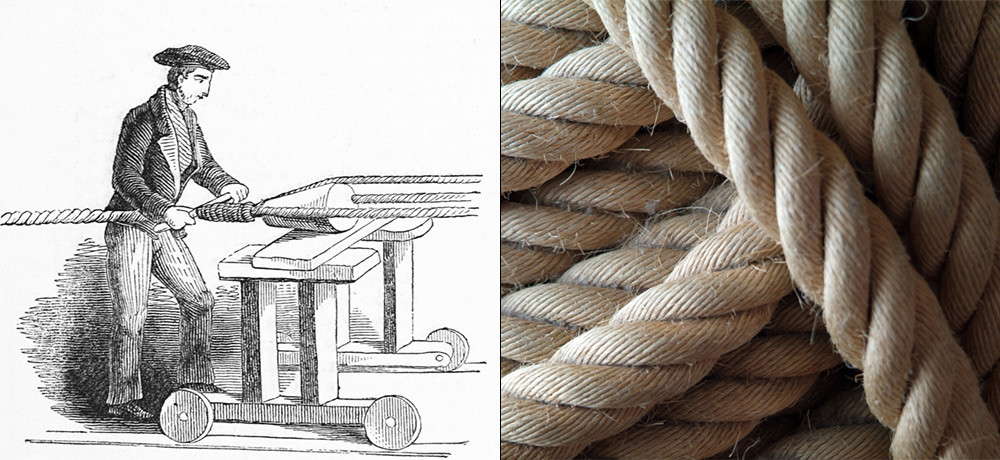

Rope making: 'laying' or twisting three strands of hemp yarn to form a rope (L). A hemp rope (R).

Getty ImagesCannabis sativa is one of the fastest growing plants on the planet, and probably one of the first to be spun into fiber in human history. Its uses are widely varied. In ancient China, the first paper was made of this plant; Johann Gutenberg’s first Bible, first American constitution and the Declaration of Independence were all printed on hemp paper.

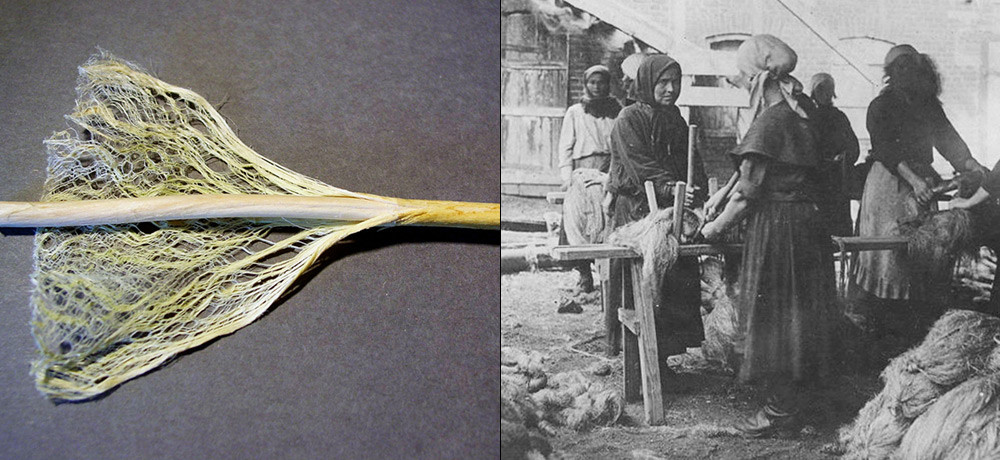

Hemp is the material produced of Cannabis sativa L. subsp. sativa, a genus of the plant used for industrial purposes. Hemp as a material is produced by soaking the stems of the plant in water. The resulting fiber has unique physical qualities: it’s too thick to be eaten by parasites like moths and so sturdy that the goods produced from it are exceptionally endurable. Canvas for clothing and bedsheets, ropes and harnesses for horses, even hemp armor – warriors of the ancient Rus’ sewed layers of hemp ropes onto their clothes, and these ropes protected them from arrows, swords, and spear hits. Also, hemp doesn’t rot, even in salty sea water, which makes it a perfect material for naval rigging and sails.

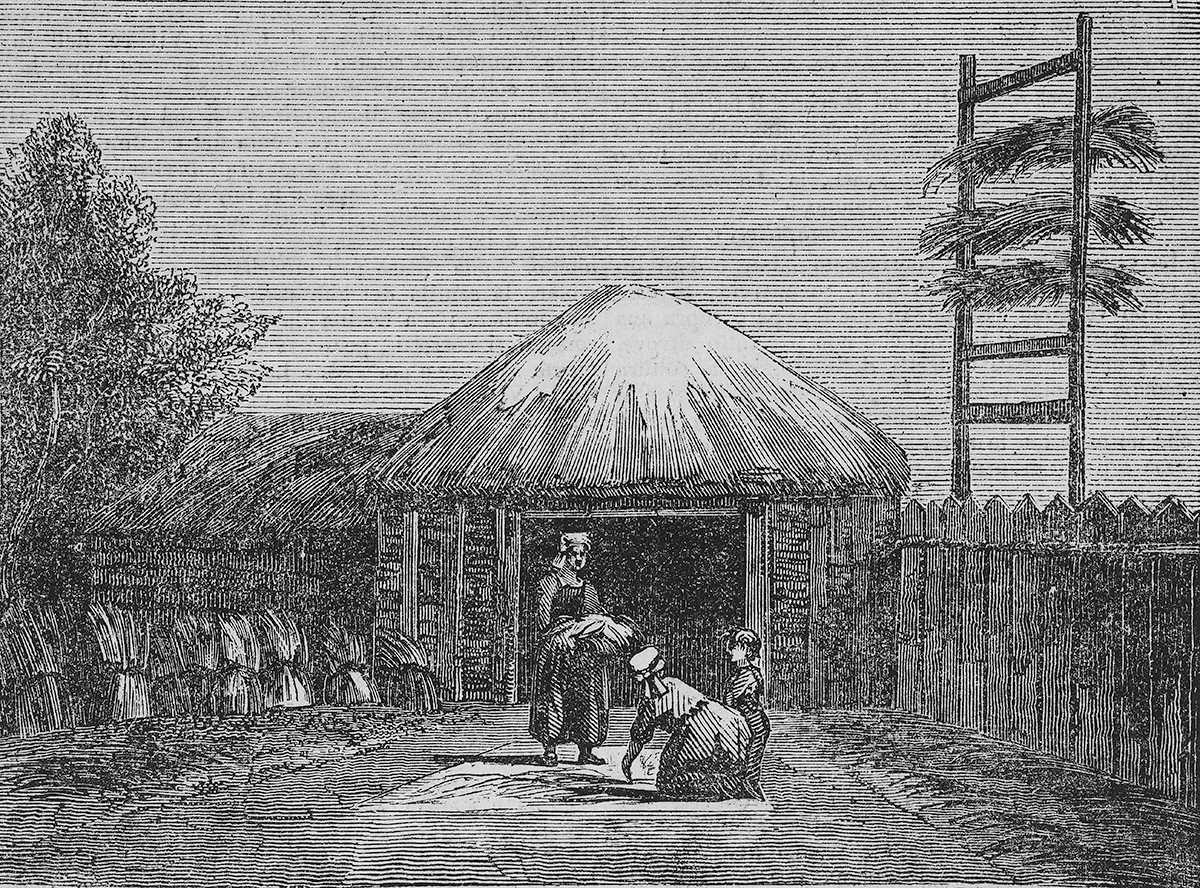

Drying of hemp and flax, Russia, illustration from Teatro universale, Raccolta enciclopedica e scenografica, 1838.

Getty ImagesIn the Russian language, there’s an adjective poskonnyi (‘посконный’), used to describe something very old, traditional, related to peasant Rus’. But not many Russians know that this adjective comes from the word poskon’ (‘посконь’), which means a male cannabis plant. Males plants are used mainly for producing industrial hemp, because they’re taller, thicker, and have no seeds that make the production of hemp fiber more complicated. So, why was traditional Russia so strongly connected to hemp?

Model of 'The Solen,' a typical Swedish vessel of the Northern War

Jim Hansson/Swedish National Maritime MuseumsIndustrial hemp has been cultivated in the Russian lands since pre-Christian times, for the production of clothing, fishing nets, and ropes, later for making horse harnesses and body armor. Peasants ate food cooked in hemp oil, as sunflower oil wasn’t widely available in the central and northern regions.

From the 16th century the Russian state started producing more hemp than it needed – because export markets opened up. Let’s see how it developed and how Russia became the world’s leading exporter of industrial hemp.

In the 16th century, Richard Chancellor established trade with the Tsardom of Russia. The British started importing Russian hemp from that time; but the heyday of this trade came under Peter the Great’s reign.

Hemp stem showing fibers (L). The process of hemp production (R).

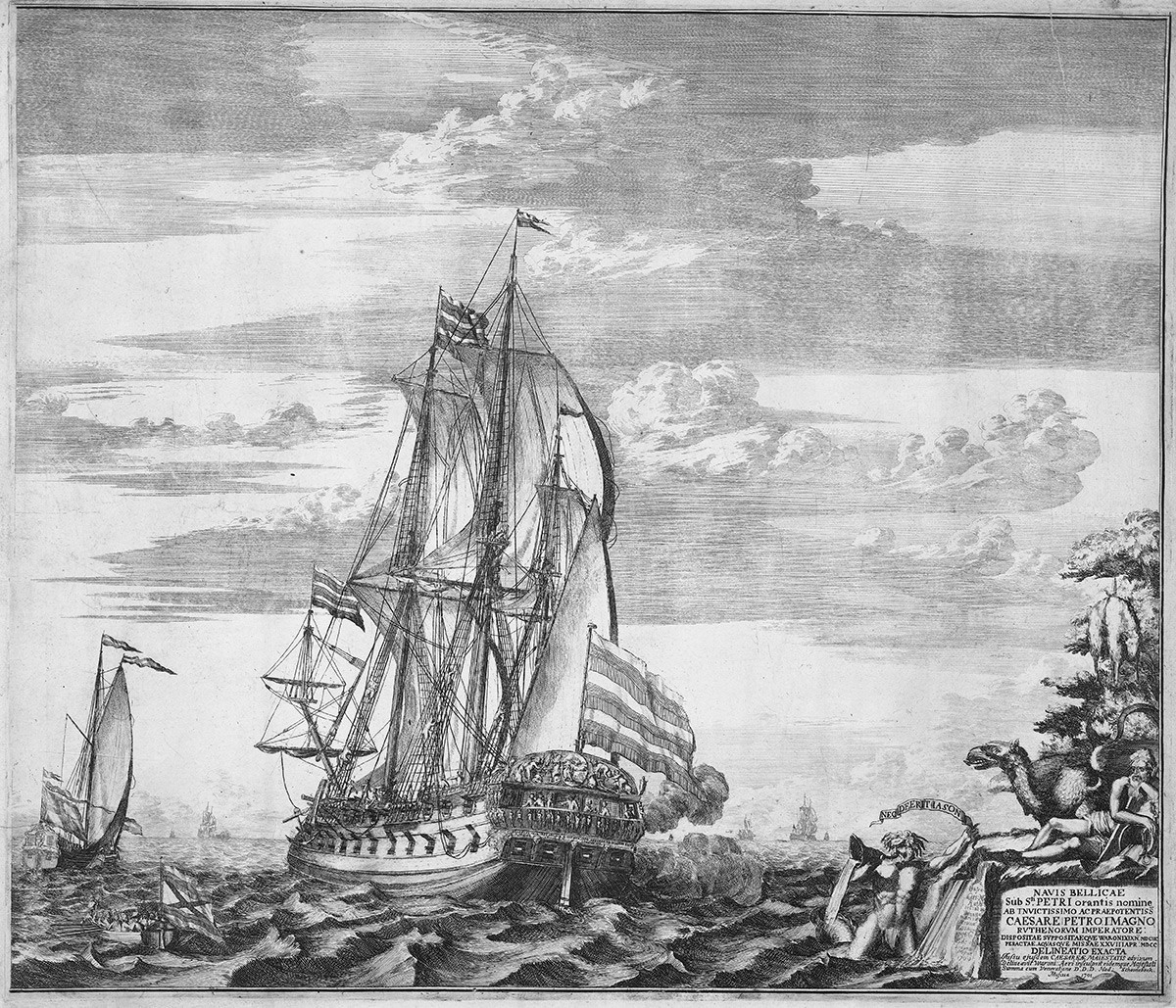

Public domain; МАММ/MDFIn the 1710s, the Great Northern War between Sweden and the coalition of Russia, Denmark-Norway and Saxony-Poland was in full swing. Britain didn’t interfere until 1717, but in fact, joined the Russian side much earlier – because of hemp.

Business and war sometimes go different ways. To fuel its naval power, Britain needed timber, iron, and hemp. Before the Northern War, Britain bought hemp and iron mostly from Sweden, but during the war, didn’t provide help for the Swedes against the Russians. Disgusted with this, Charles XII of Sweden pushed up the prices for hemp and iron.

Flagship 'Goto Predestinatsia' (The Providence of God) built by Peter the Great at Voronezh, 1700, 1701. Found in the collection of Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Artist : Schoonebeek (Schoonebeck), Adriaan (1661-1705).

Getty ImagesIn 1715, Britain started importing iron from Russia, and Peter understood he should also export hemp. The same year, the Russian tsar issued an order to increase the production of hemp and at the same time, offered the British lower prices than Sweden: while the Swedes sold a ton of hemp for £22, Peter offered it for £6. And, as British naval officers confirmed, Russian hemp was much better than Swedish.

Along with logistics, for the English merchants, one ton of Russian hemp material was a little more than £10! And crucially, the Russian supply of hemp was endless, compared with Sweden’s relatively paltry stocks… By protecting its merchant ships that had to get to the Russian Baltic shores through Swedish-controlled waters, Britain, in fact, took the Russian side in the war. In 1715, 200 English merchant ships arrived at St. Petersburg and Riga, buying enormous amounts of hemp cloth and ropel and providing Russia with money needed to continue the war.

The getting in of the hemp in Russia.

Getty ImagesEventually, as we know, Sweden was defeated in 1721, and Russia became an Empire. Until the beginning of the 19th century, Russia was the sole exporter of hemp to Great Britain (96 percent of the British rigging was made of Russian hemp), while politically, the two European superpowers were against each other in many wars during the 18th century.

Over 32,000 tons of hemp was exported from Russia annually in the 18th century. Peasants of the Oryol, Kaluga, Kursk, Chernigov, and other regions made profits by cultivating the plant and producing hemp material.

The emblem of the town of Dmitrovsk, Oryol region, Russia. A cannabis plant can be seen in the middle of the lower part.

But in the early 19th century, Britain started importing cotton from America, and jute fiber, which was cheaper in production, started being used for naval rigging; Russian hemp imports to Britain declined. Still, Russia continued to export hemp to more than 10 countries in Europe. In the second half of the 19th century, hemp accounted for between 50 to 74 percent of Russian exports, and by the end of the century, Russia produced 140,000 tons of hemp – 40 percent of all hemp produced in Europe. But by the beginning of the 20th century, jute rigging had replaced hemp rigging almost everywhere, and steam ships, used since the mid-19th century, replaced sailing ships. So the hemp power of the Russian Empire came to an end. To the present day, the town of Dmitrovsk in Oryol region bears the image of a cannabis plant on its emblem, reminding us that this region was the leading one in hemp production in olden times.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox