The National Nuclear Centre in Kurchatov.

Alexander Lyskin/SputnikIn 1965, the USSR launched ‘Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy’ - a program that intended to use the scariest weapon in the world for peaceful purposes. The gist of it was to use 124 underground explosions for the purpose of creating artificial aquifers, as well as channels for connecting rivers, and developing mines for the extraction of precious materials. The idea was that the blowing up nuclear explosives underground would help stop radiation from contaminating the surface above ground that would have led to an environmental catastrophe.

The Soviets weren’t the only ones (they weren’t even the first) to use nuclear weapons for peaceful purposes. In 1957, the United States had initiated ‘Project Plowshare’, which saw the use of 27 nuclear explosives for industrial purposes. The program ended in 1973.

Aside from using its existing nuclear arsenal, the USSR was developing specialized “clean” charges, with a reduced nuclear yield.

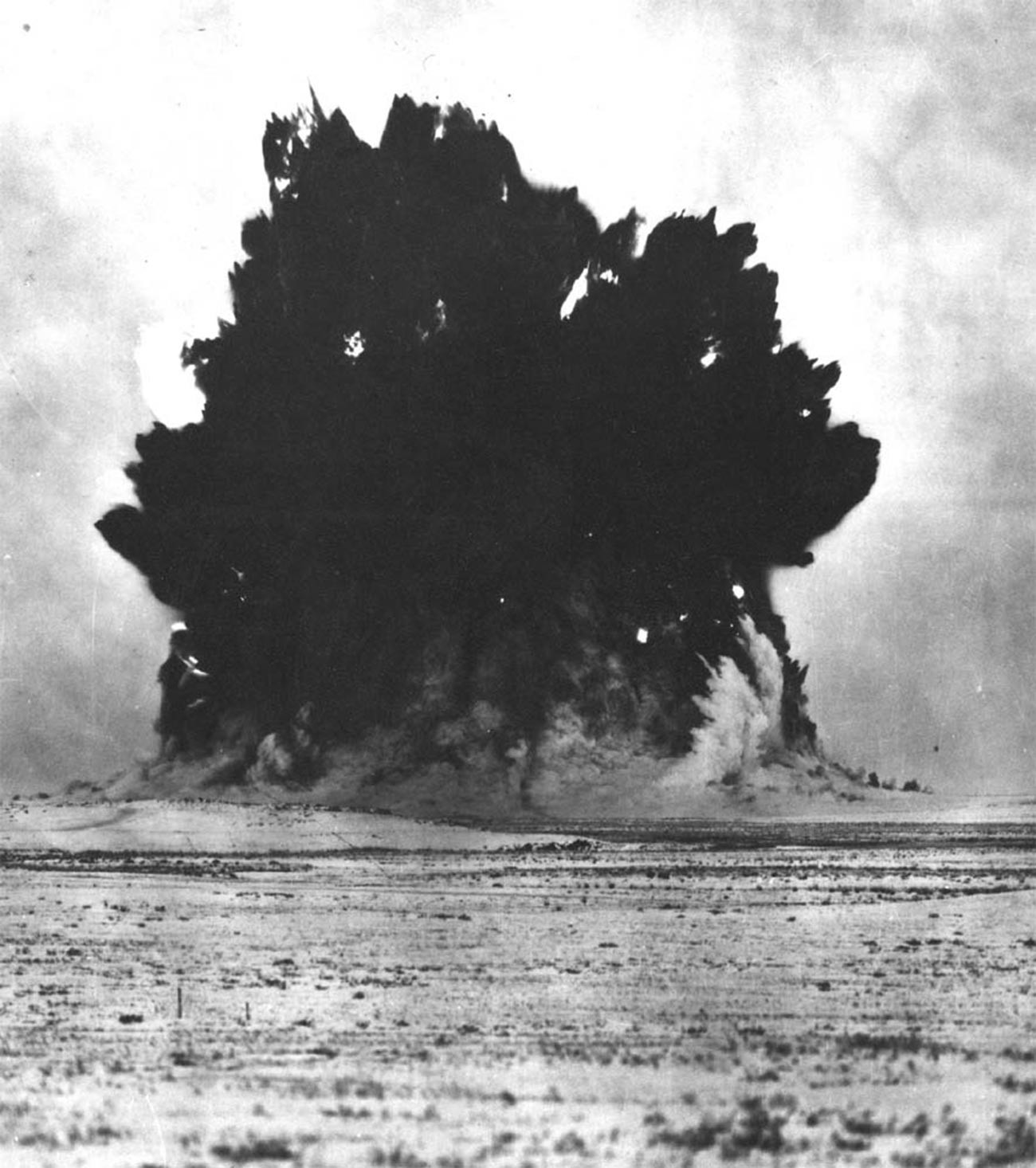

The first underground industrial explosion was carried out on January 15, 1965 in the floodplain of the Chagan River in Kazakhstan. This led to the creation of a funnel 500 meters in diameter and 100 meters in depth, which in turn created an artificial aquifer. “The ‘miracle lake’ was a frightening sight, not so much in terms of the radiation - of which there were substantial amounts in the river’s breastwork, but in terms of the blackness of the lifeless soil that bulked up around it, the inside-out lumps of the Earth’s insides,” nuclear physicist Viktor Mikhailov remembered, upon visiting the aquifer after the blast.

These “lakes” were meant to serve as sources of water for agriculture (irrigation, cattle breeding, etc.). Forty such reservoirs had been planned on the territory of Kazakhstan alone.

Pollution monitoring of the Chagan Lake carried on for several years. Some 36 species of fish were introduced into the lake (including Amazonian piranhas!), as well as 150 species of plants, dozens of species of mollusks, amphibians, reptiles and mammals. However, 90 percent did not survive, while others developed a variety of mutations. Among other things, fishermen once caught a gigantic freshwater crayfish weighing in at 34 kilograms (average crayfish weigh up to just 3.5 kg)!

Today, Lake Chagan is listed by the Kazakh government as among the localities that suffered particularly adverse effects of nuclear testing. Radioactive levels in the water exceed acceptable norms by hundreds of times, making it unsuitable for agricultural use, let alone drinking. Nevertheless, this doesn’t stop locals from using the lake as a drinking source for their cattle.

A slightly more merciful fate befell another artificial aquifer created under similar conditions. Lake Yadernoe (literally meaning “Nuclear”!) in the north of Perm Region, in Ural, is actually far more benign than its name suggests, with radioactivity levels staying within acceptable limits. The lake has become a favorite with local fishermen and mushroom pickers.

Lake Yadernoe.

WikimapiaNot every industrial explosion in the USSR went as planned - there were a few occasions when radioactive materials escaped to the surface. The most famous of these cases is the ‘Globus-1’ project, which entered history as the “Ivanovo Hiroshima”. On September 19, 1971, in the central part of Russia, a mere 363 kilometers from the Red Square, a botched underground detonation on the shores of the Shachi River ended with the contamination of the surrounding area, causing a sharp subsequent spike in cancer cases in nearby towns and villages in Ivanovo Region. Authorities partially cleaned up the mess by transporting contaminated soil away from the Shachi shore, but toxicity persisted through the mid-2010s.

Despite taking every precaution, it was impossible to avoid the contamination of mineral mines and the environment using nuclear explosives for industrial purposes. Thus, in 1988, the program was ended. The technique is banned across the world today, thanks to a series of international agreements.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox