When in 1863, a Polish uprising (or the so-called ‘January Uprising)’ began in the western part of the Russian Empire, agriculture student Michal Jankowski was just 21. Like hundreds of other young Poles, he immediately joined the rebels, who were trying to restore the independence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was lost in the 18th century, when the Commonwealth was divided between other great powers.

January Uprising.

Public DomainParticipation in that uprising cost Michal dearly. Stripped of his title and all his fortune, he was sentenced to eight years of hard labor in Siberia. A few years after, Jankowski and thousands of other exiled Poles were pardoned. However, they were forbidden from returning to their homeland and had to live in the wild, yet undeveloped eastern part of the empire.

Jankowski spent endless, monotonous days hunting in the Siberian wilderness, but one day fate gave him a chance to completely change his life. Two of his Polish friends, who too had been sentenced to exile, zoologists Victor Godlewski and Benedykt Dybowski, invited him on a scientific expedition. For two years, they traveled along the Amur River, exploring the area’s flora and fauna, until they reached the Pacific coast. Michal returned from this trip a different man: one who was madly in love with science and with the Russian Far East.

March to Siberia.

Artur GrottgerJankowski, who had Russified his name to Mikhail Ivanovich (Yanovich) Yankovsky, settled in Ussuriland in the Russian Far East. In 1874, with Dybowski’s assistance, he gained the position of a gold mine manager on Askold Island, 50 km from Vladivostok.

Jankowski coped with his new duties well. He successfully defended the island from raids by Chinese bandits (the Honghuzi) and poachers, established an effective gold mining operation and opened the first weather station on the island. Through his efforts, the population of sika deer, which had become almost extinct on the island, was restored, while the nursery Jankowski had established for these animals was the only one in the world at the time.

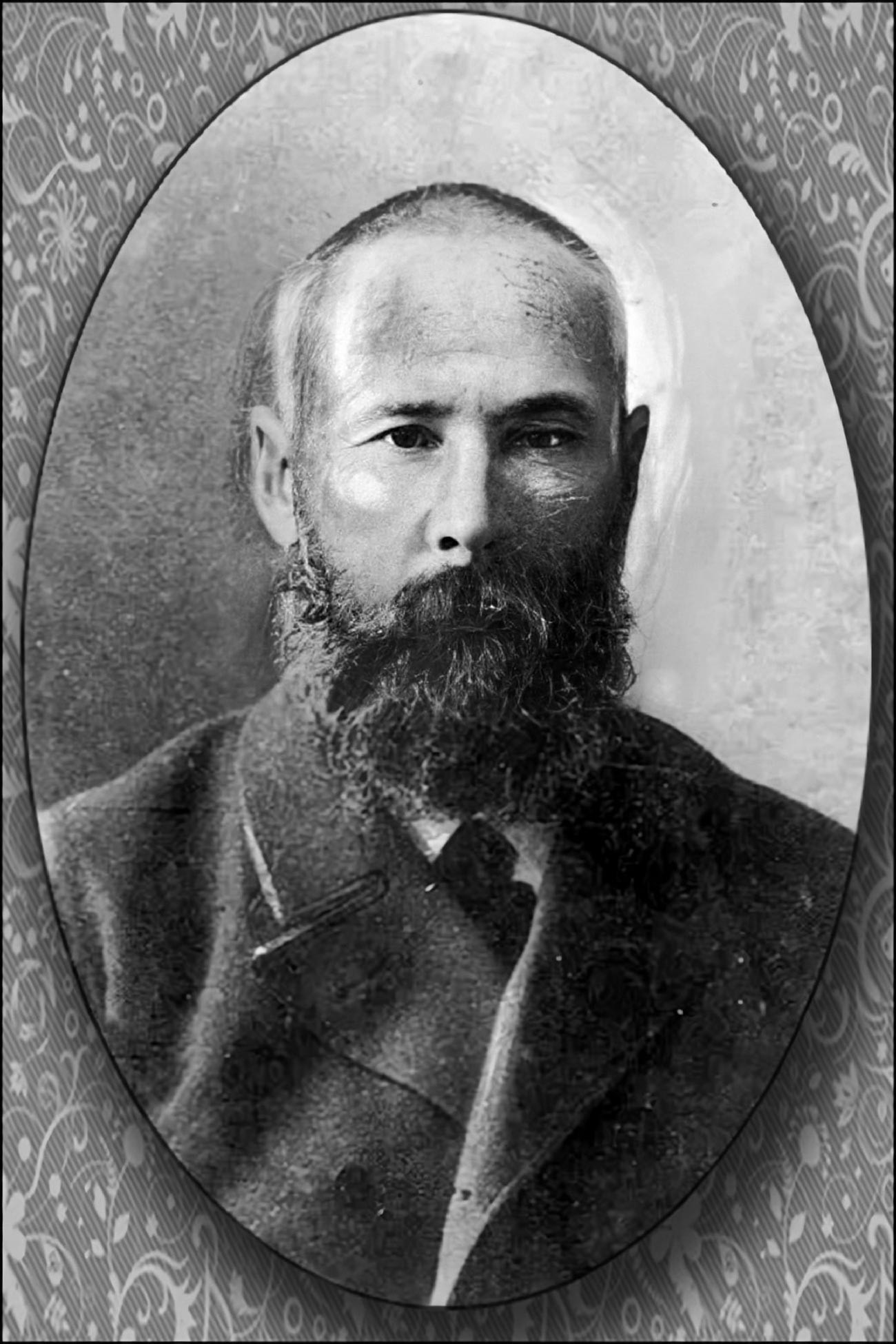

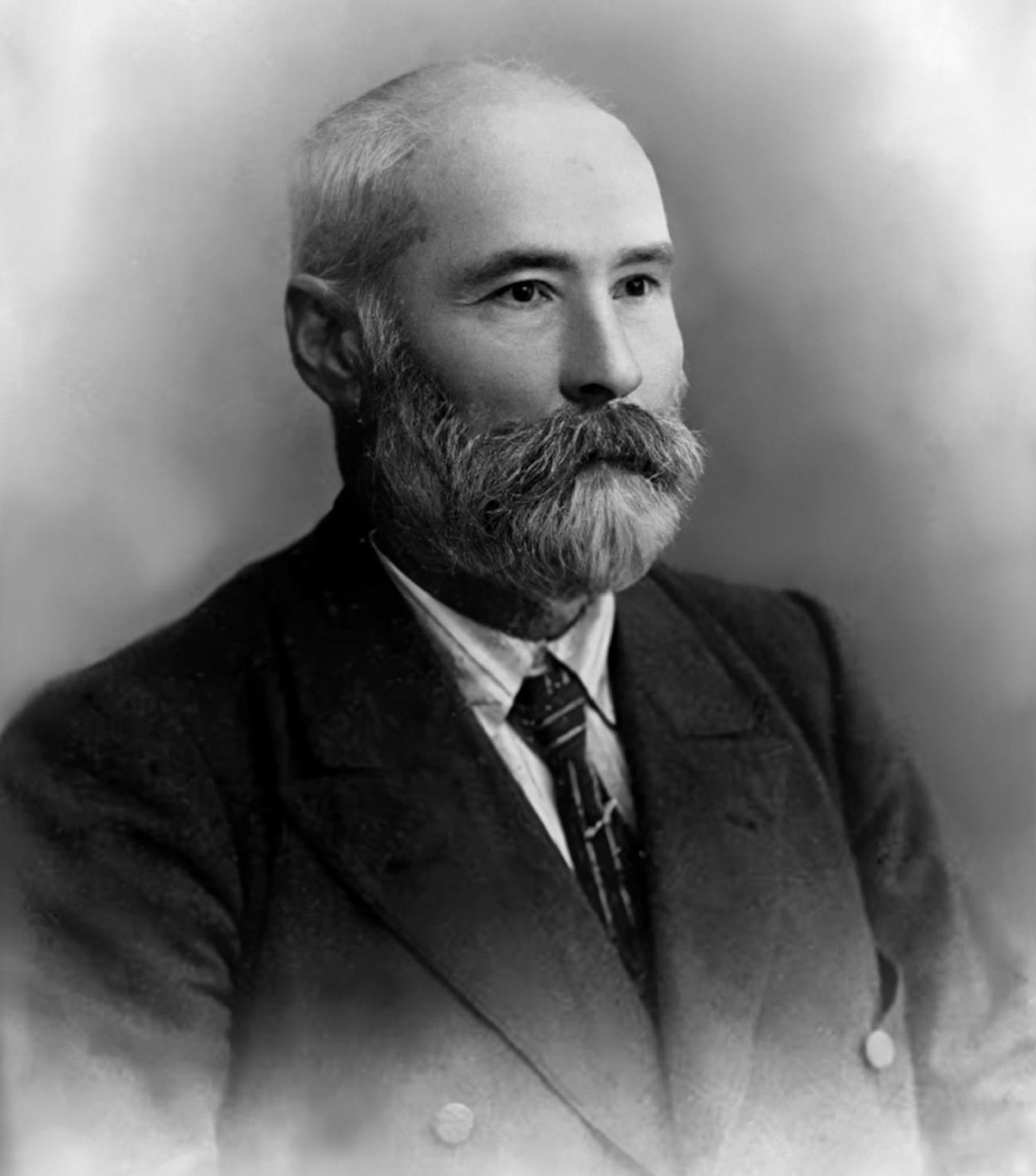

Mikhail Yankovsky

Public DomainJankowski did not give up his scientific pursuits either. He explored the nature of Askold, put together dozens of collections of birds, plants and insects and sent them to museums around the world. The Russian Geographical Society awarded him a silver medal for his research paper ‘Askold Island’.

In 1879, Mikhail Yankovsky had his aristocratic title restored. However, he did not seek to return to Poland: by then, the Russian Far East had become his second home. He had started a family there and had found an occupation he loved.

After five years on Askold, the Yankovskys moved to the Sidemi Peninsula on the western coast of Peter the Great Bay, not far from Korea. Those were wild lands, teeming with tigers and the Honghuzi. The family's house resembled a small fortress, ready for a long siege. Mikhail always kept a loaded rifle at hand. For his amazing shooting accuracy, the local Koreans nicknamed Yankovsky ‘Nenuni’, which means “four-eyed”.

Having acquired vast territories on the peninsula, Mikhail Ivanovich was able to reveal his entrepreneurial talent to the full.

Yankovsky family's house.

Archive photo“The farm was started from scratch. The stud farm began in 1879 from a nondescript Russian stallion called Ataman and a dozen tiny Korean, Manchu and Mongolian fillies, four of which with all their offspring were killed by a tiger in the very first winter,” his son Yuri recalled. Nevertheless, Mikhail managed to develop a new breed of horses adapted to the conditions of the Far East. The so-called Yankovsky horse became popular with peasants, was purchased by the military for the needs of cavalry and horse artillery, and often took prizes at races and agricultural exhibitions. The stud farm of the enterprising Polish industrialist sold up to 100 of these horses every year.

In Sidemi, Mikhail Yankovsky continued to breed sika deer and founded Russia’s first plantation of ginseng, a plant whose medicinal properties are particularly valued in oriental medicine. Sadly, tens of thousands of unique roots were forgotten and lost during the Russian Civil War from 1917 to 1922.

Commerce did not prevent Mikhail Ivanovich Yankovsky from pursuing his beloved science. While exploring the Russian Far East, he continued his research in geography, entomology, ornithology and many other fields.

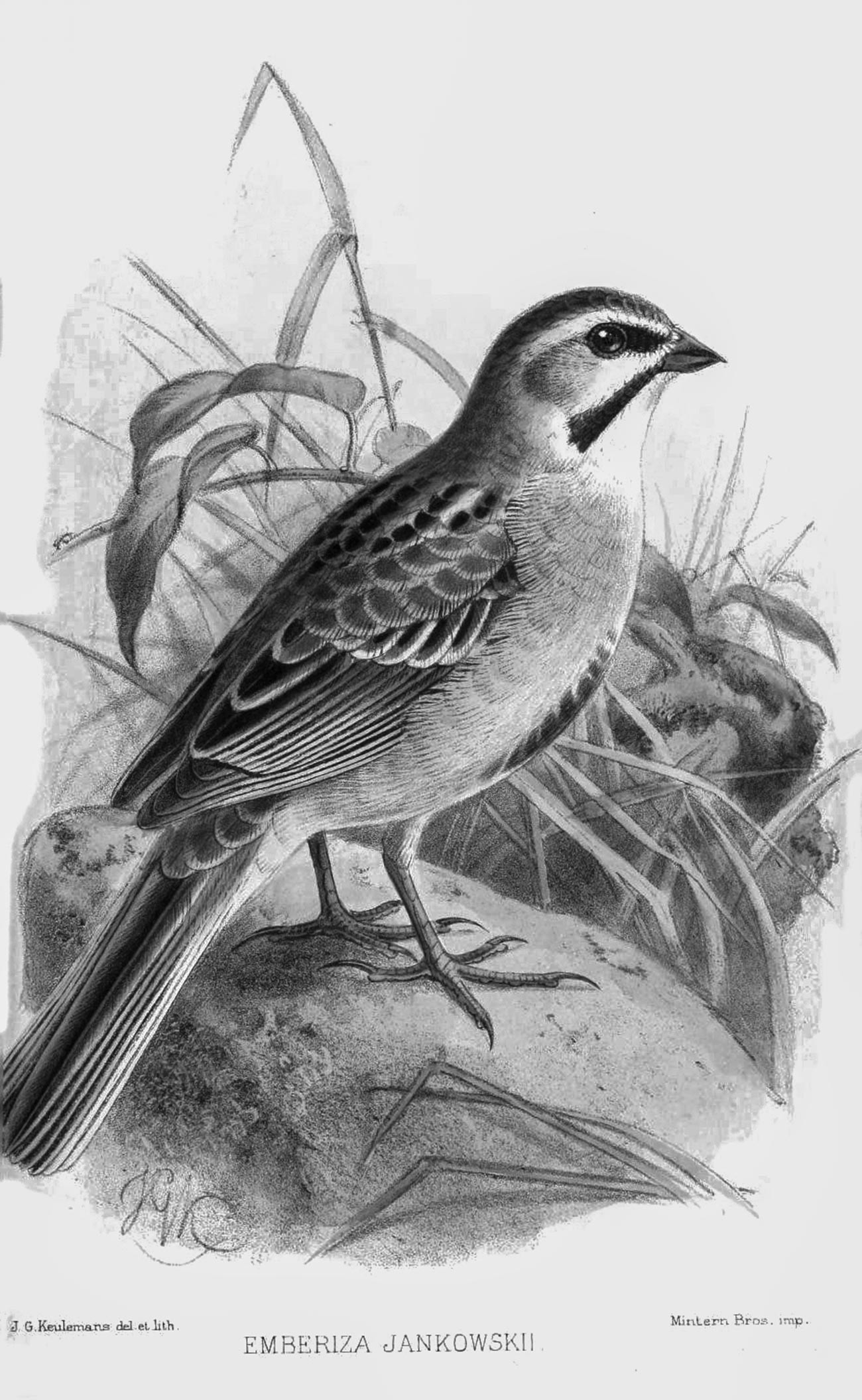

Yankovsky discovered several species of beetles, about 100 species of day and night butterflies, 17 of which were named after him. He researched and described a rare bird that lives exclusively in the Far East and is known today as the Jankowski's Bunting.

Jankowski's Bunting.

Public DomainHe also made a significant contribution to archeology. The archaeological culture of the southern Primorye region discovered by Yankovsky was also named after him. Interestingly, this research was sponsored by Julius Bryner, a major local philanthropist, the grandfather of the famous Hollywood actor Yul Brynner (who added another “n” to his last name).

In the early 20th century, health problems forced Mikhail Ivanovich to exchange the harsh Far Eastern climate for the warmth of the Black Sea coast. Despite moving to Sochi, he regularly visited his beloved land until his death in 1912.

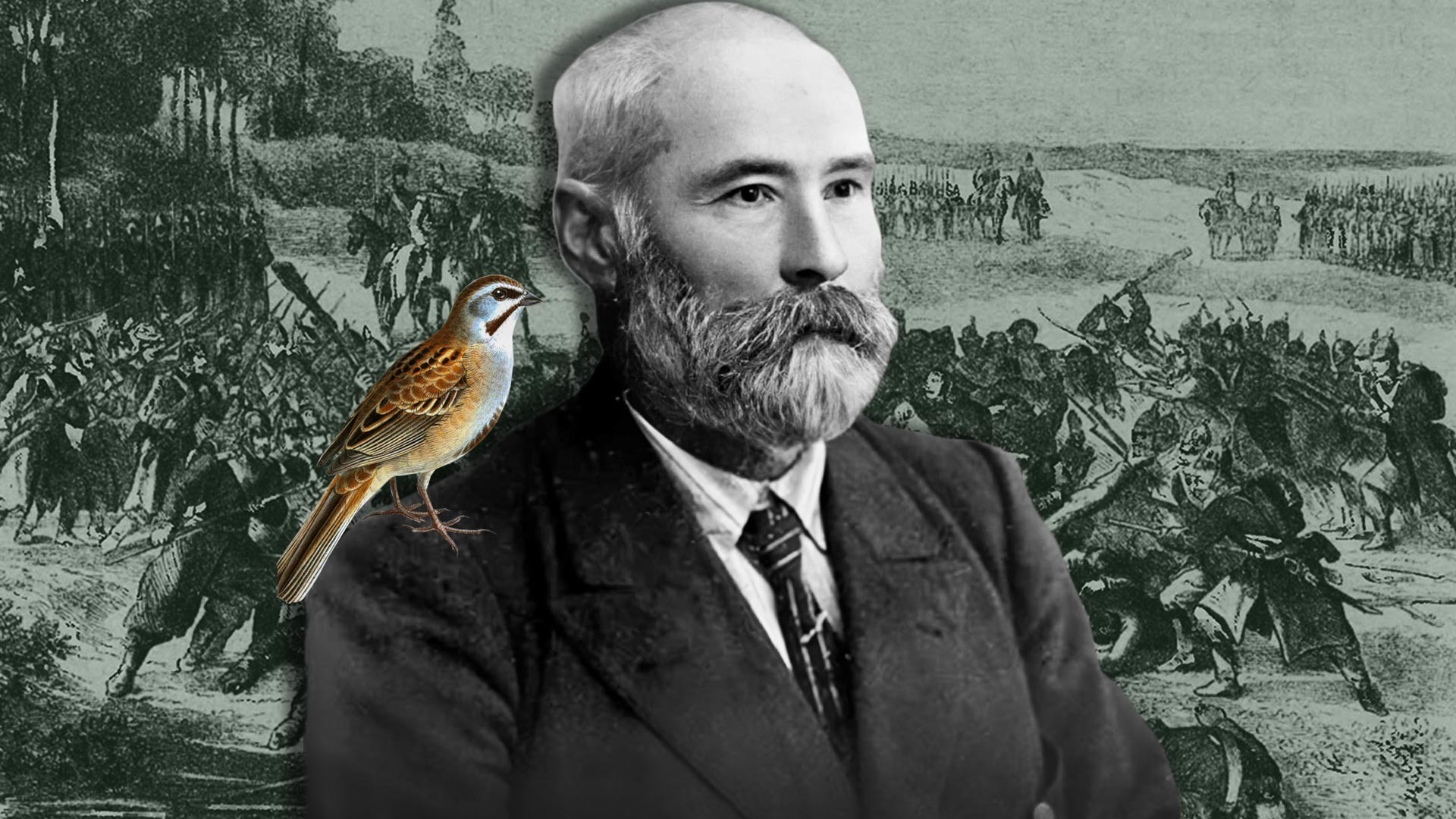

Mikhail Yankovsky.

Public DomainThese days, the name of the scientist and industrialist Mikhail Yankovsky is well known across the Russian Far East. The Sidemi Peninsula has been renamed into Yankovsky Peninsula, while several streets in Vladivostok and several settlements in Primorsky Krai have been named after him. A plaque next to the monument to this outstanding figure erected in the village of Bezverkhovo says: “He was a nobleman in Poland, a convict in Siberia and found shelter and glory in Ussuriland. What he has done is an example to the future masters of this land.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox