After World War I, the German army, once the strongest in Europe, presented a pitiful sight. Under the Treaty of Versailles, it could not number more than 100,000 soldiers. The Germans were forbidden to have armored troops, military aviation, a submarine fleet and were banned from carrying out military research and development.

However, the Reichswehr, as the armed forces of the Weimar Republic were called, had no intention of putting up with its pitiful fate. The German military was determined to develop their armed forces, but it was impossible to do on German territory, under the watchful eye of the Allied Powers.

A solution was soon found: Germany turned to Soviet Russia with an offer of cooperation. That rogue state, which had just lived through a devastating Civil War and foreign intervention, was surrounded by hostile states and was not recognized by a single global power. As the commander-in-chief of the Reichswehr, Hans von Seeckt, noted: “The Versailles diktat can only be broken through close contact with a strong Russia.”

Moscow was happy to end its blockade by establishing contacts with Germany. In addition, military cooperation with the still highly skilled German military was vital for the modernization of the Red Army.

Negotiations on military cooperation between Moscow and Berlin began before the end of the Soviet-Polish war (1919-1921). Both countries shared a strong affinity based on anti-Polish sentiments: Just like Russia, Germany too had to cede parts of its territory to Poland, as was the case during the Greater Poland uprising in 1919. Nevertheless, there was no talk of any military-political alliance.

Hans von Seeckt (C) and the Reichswehr officers.

BundesarchivIn 1922, during talks in the small Italian town of Rapallo, the Germans and the Bolsheviks agreed to restore diplomatic relations. While publicly they were signing economic agreements, unofficially, negotiations were under way on cooperation in training military pilots and tank crews and the development of chemical weapons.

As a result, in the 1920s, several German secret schools, training and military research centers were opened in Russia. The government of the Weimar Republic spared no expense to maintain them, allocating up to 10 percent of the country’s military budget for the purpose annually.

The Soviet-German military cooperation was shrouded in an atmosphere of complete secrecy. Berlin needed that secrecy far more than Moscow did. In 1928, Soviet envoy to Germany Nikolai Krestinsky wrote to Stalin: “From the state point of view, we are not doing anything contrary to any treaties or norms of international law. Here, the Germans are violating the Treaty of Versailles, and it is they who need to fear exposure and worry about maintaining secrecy.”

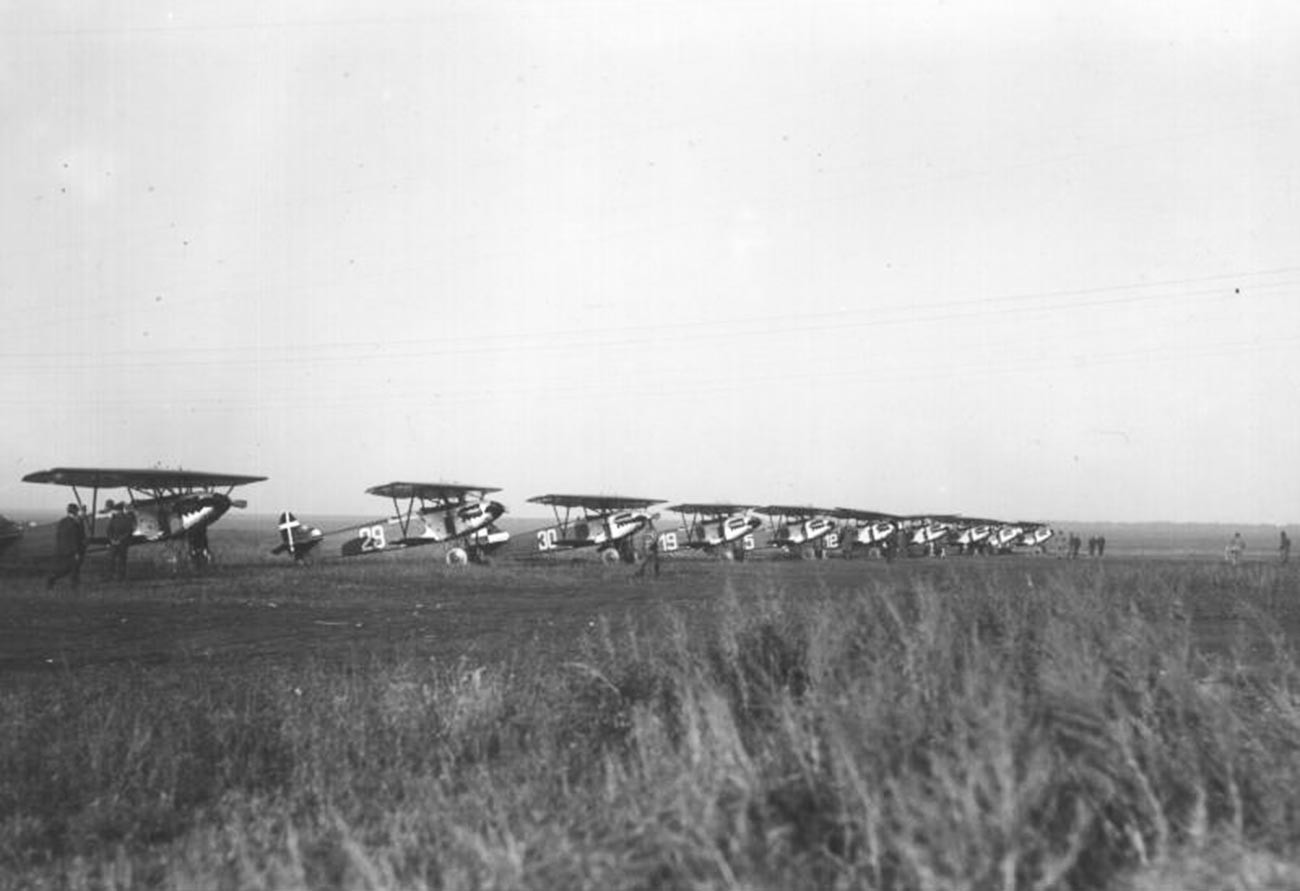

The Lipetsk facility.

BundesarchivIn 1925, a German aviation school was secretly established near Lipetsk (about 400 km from Moscow), fully funded by Germany. It was agreed that the school would train both German and Soviet pilots, who were borrowing experience from their Western colleagues.

In addition to providing academic training, the school carried out tests of new aircraft, aviation equipment and weapons and practised air combat tactics. The planes were purchased by the German Defense Ministry from third countries via intermediaries and delivered to the territory of the USSR. The first batch consisted of 50 Dutch Fokker D.XIII fighters that were delivered to the Lipetsk air center disassembled.

A German pilot’s training program in the USSR lasted about six months. They would arrive in Lipetsk secretly, under assumed names, and would wear Soviet uniforms without insignia. Before coming to Lipetsk, they would be officially dismissed from the Reichswehr, and would then be reinstated upon their return. Pilots who were killed while testing aircraft were brought home in special boxes signed “machine parts”.

Dutch Fokker D.XIII fighters in Lipetsk.

BundesarchivIn the eight years of its existence, the Lipetsk aviation school trained over 100 German pilots. Among them were such important figures in the future Luftwaffe as Hugo Sperrle, Kurt Student and Albert Kesselring.

In the early 1930s, both Germans and Russians began to lose interest in the Lipetsk aviation school. The former, bypassing many of the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, were already partially able to train their armed forces on their territory. For the latter, after the Nazis came to power in 1933, military and technical cooperation with an ideological enemy was impossible. That same year, the aviation school was closed.

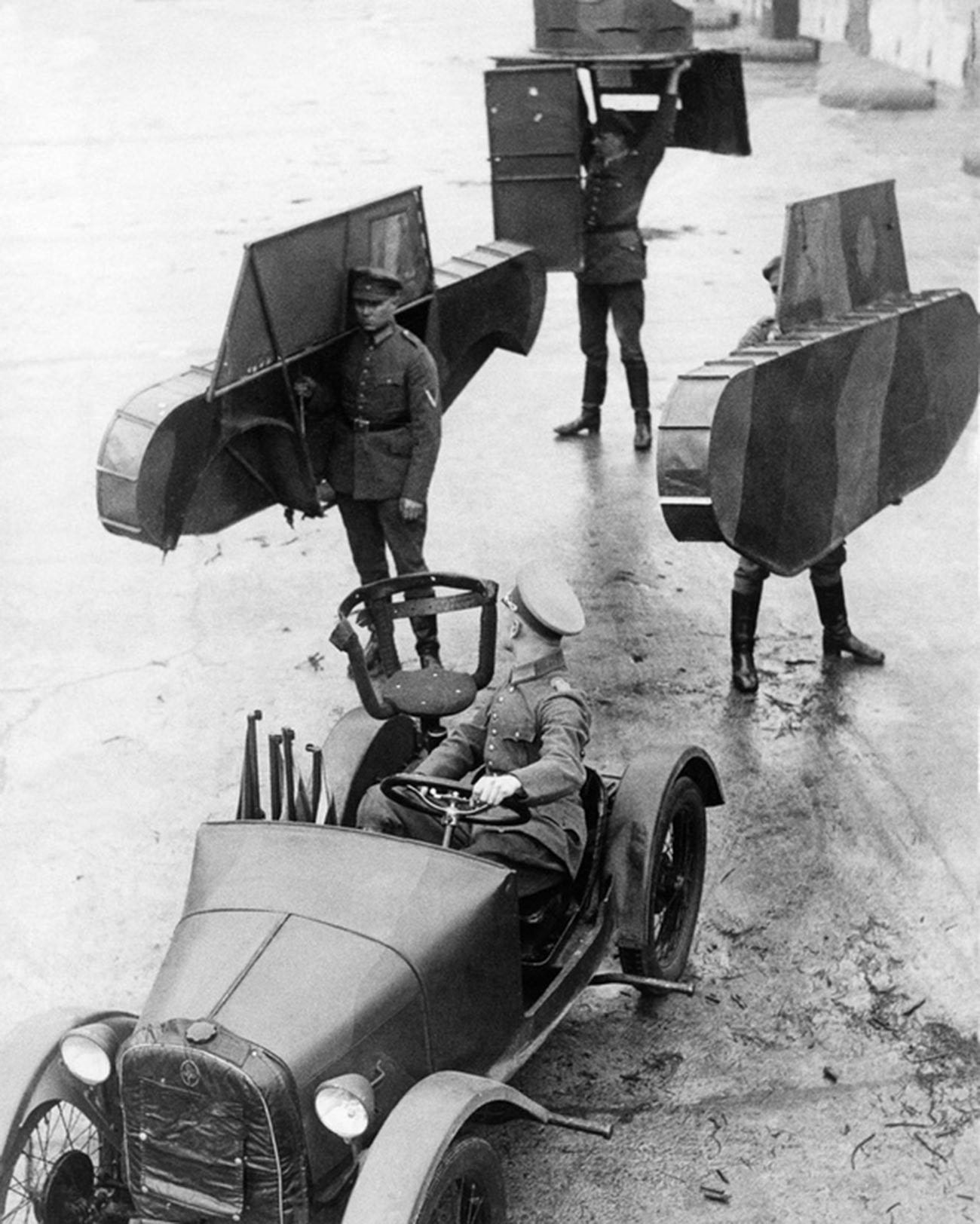

The Kama facility.

Archive photoAn agreement on setting up a German tank school in the USSR was signed in 1926, but the school only opened in late 1929. Situated near Kazan (800 km from Moscow), the Kama school was referred to in Soviet documents as ‘Technical Training Courses for the Air Force’.

The Kama facility operated along the same lines as the Lipetsk one: complete secrecy, funding mainly from the German side and joint training of Soviet and German tank crews. The training grounds near Kazan were actively used for testing tank armaments, communications, studying armored warfare tactics and the art of camouflage and practising interaction within tank groups.

Tanks for trials, so-called ‘Big Tractors’ (“Grosstraktoren”), were secretly produced for the German Defense Ministry by the country’s leading enterprises (Krupp, Rheinmetall and Daimler-Benz) and were delivered to the USSR disassembled. For its part, the Red Army provided T-18 light tanks and British-made Carden Loyd tankettes it had in service.

As was the case with the Lipetsk aviation school, Kama could not continue to operate after 1933. In the short period of its existence, it trained 250 Soviet and German tank crewmen. These included future Hero of the Soviet Union Lieutenant General Semyon Krivoshein, Wehrmacht general Wilhelm von Thoma and Heinz Guderian's chief of staff Wolfgang Thomale.

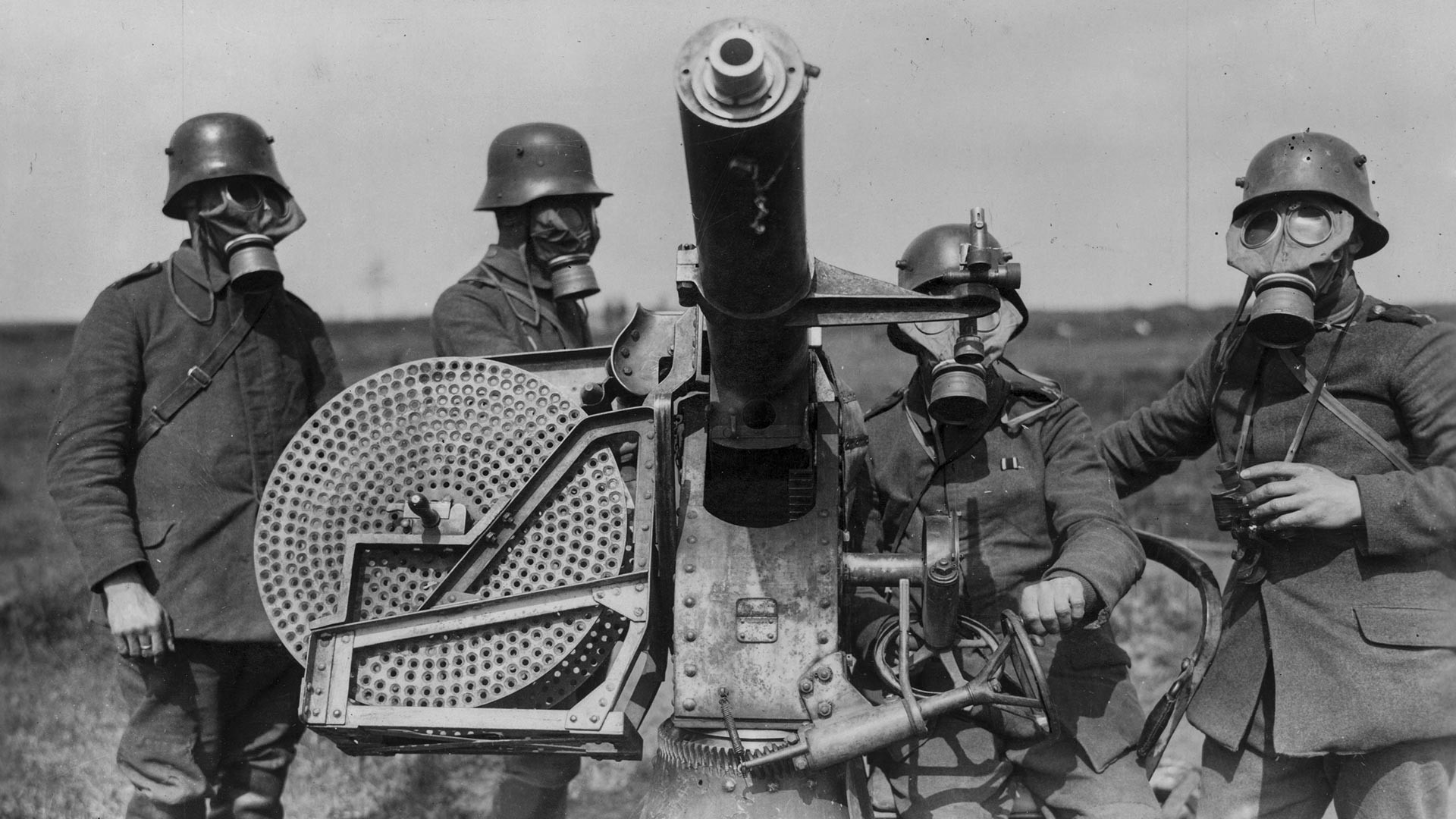

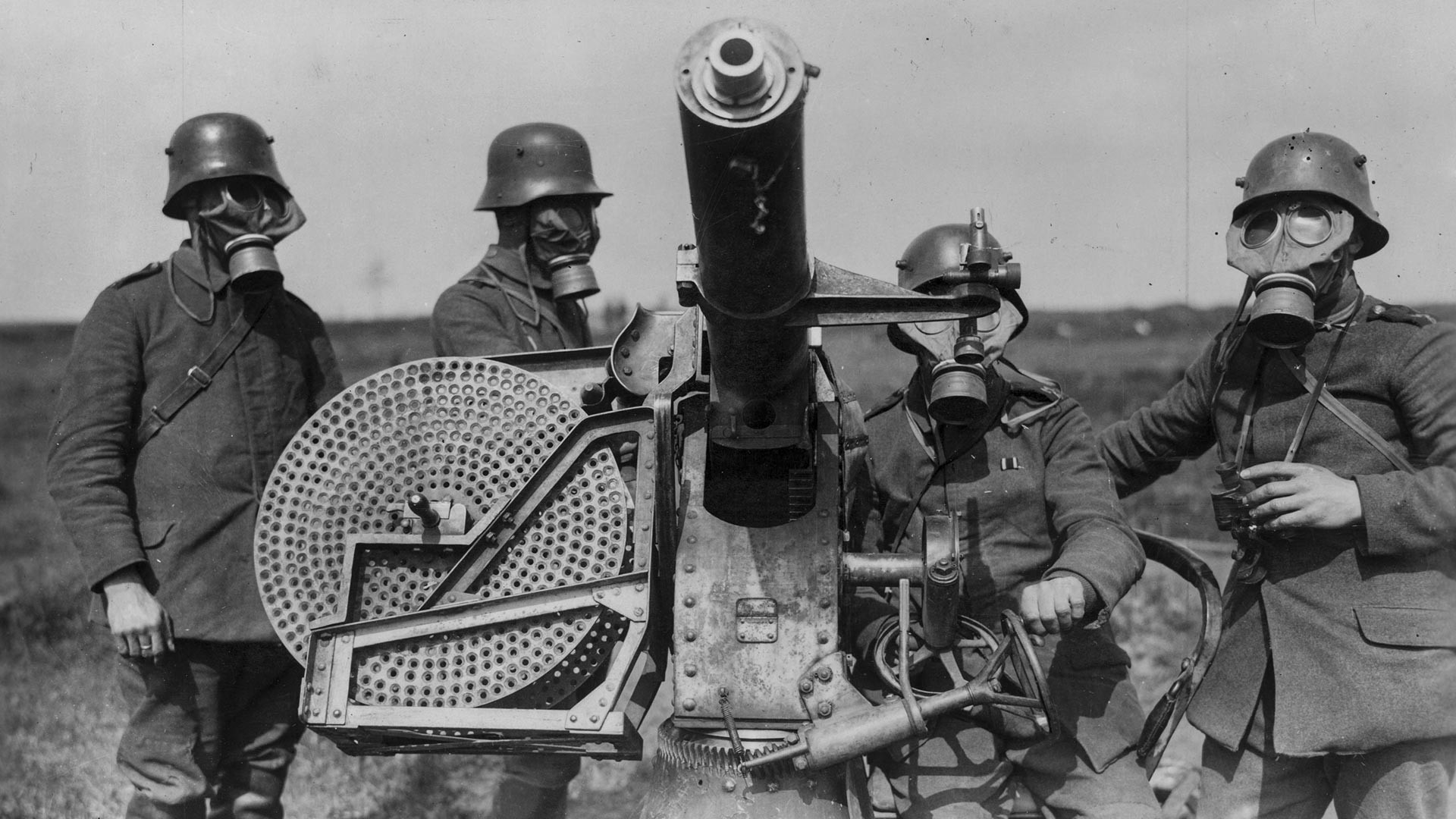

German personnel of the Tomka facility.

BundesarchivThe Tomka school of chemical warfare in Saratov Region (900 km from Moscow) was the most secret Reichswehr facility on Soviet territory. It consisted of four laboratories, two vivariums, a degassing chamber, a power station, a garage and living quarters. All the equipment, several aircraft and guns were secretly brought from Germany.

Tomka had a permanent German personnel of 25 people: chemists, biologists-toxicologists, pyrotechnics and artillerymen. In addition, the school had Soviet specialists as trainees, since they did not have as much experience in the use of chemical weapons as their Western colleagues.

Tests at the facility were carried out between 1928-1933. They consisted of spraying poisonous liquids and toxic substances with the use of aviation and artillery and in the decontamination of territory.

Of all their facilities on the territory of the USSR, the Germans held on to the Tomka one the most. In addition to the opportunity to bypass the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, they also took into account the geographical factor: in a relatively small and densely populated Germany, finding suitable sites for testing chemical weapons was not easy. Despite the fact that for the Soviet side this facility brought both money and invaluable experience, politics prevailed and Tomka was shut down the year the Third Reich was born.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox