One day in February 1955, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev received an anonymous letter claiming to be from a “Soviet citizen and a mother”. The author of the letter described something unheard of in the USSR: an undercover brothel frequented by multiple high-ranking officials, who lured young female students there to have sex with them. The woman claimed her daughter was one of the victims and asked the Soviet leader to close the lewd establishment and punish its founders and patrons.

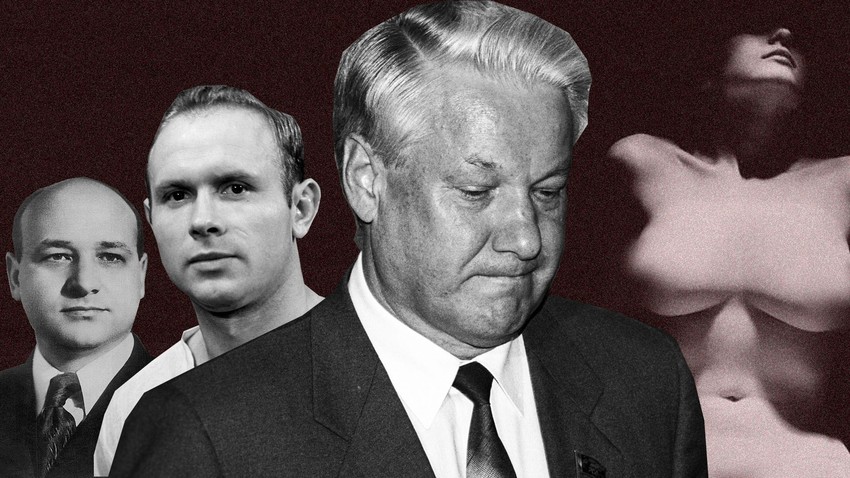

The author of the letter said that among other powerful individuals, her daughter had named George Alexandrov, Minister of Culture of the USSR and Alexander Yegolin, a Soviet literary critic and a party official.

George Alexandrov, Minister of Culture of the USSR.

МАММ/MDF/russiainphoto.ruKhrushchev must have found the letter quite timely, as the potential culprits were also Khrushchev’s political foes. The Soviet leader demanded an immediate investigation.

The investigation revealed that the allegations were legitimate and that Alexandrov, Khrushchev’s political foe, was not the only powerful figure involved. Names of other political figures, powerful ideologues and propagandists, famous academicians, and even that of an ex-Education Minister under Stalin Sergei Kaftanov, were revealed in the context of the sex scandal.

All of them were frequent guests at a house of relatively unknown dramatist Konstantin Krovoshein, who recruited young women from the various theater and choreographic schools for his sex parties.

When accused, Minister of Culture Alexandrov confessed and begged the party leaders for mercy and a chance to redeem himself. Nobody was imprisoned, except Krovoshein, the brothel’s nominal founder. Instead, Alexandrov lost his ministerial office and was transferred to the Belorussian SSR, where he worked as a department head at the Institute of Philosophy at the local Academy of Sciences.

The biggest sex scandal in the history of the Soviet Union became known as the ‘Gladiator’s case’, because, according to one version, one of the accused men defended himself by saying he was only guilty of stroking (which is “gladit” in Russian). From then on, those involved in the case were referred to as ‘gladiators’.

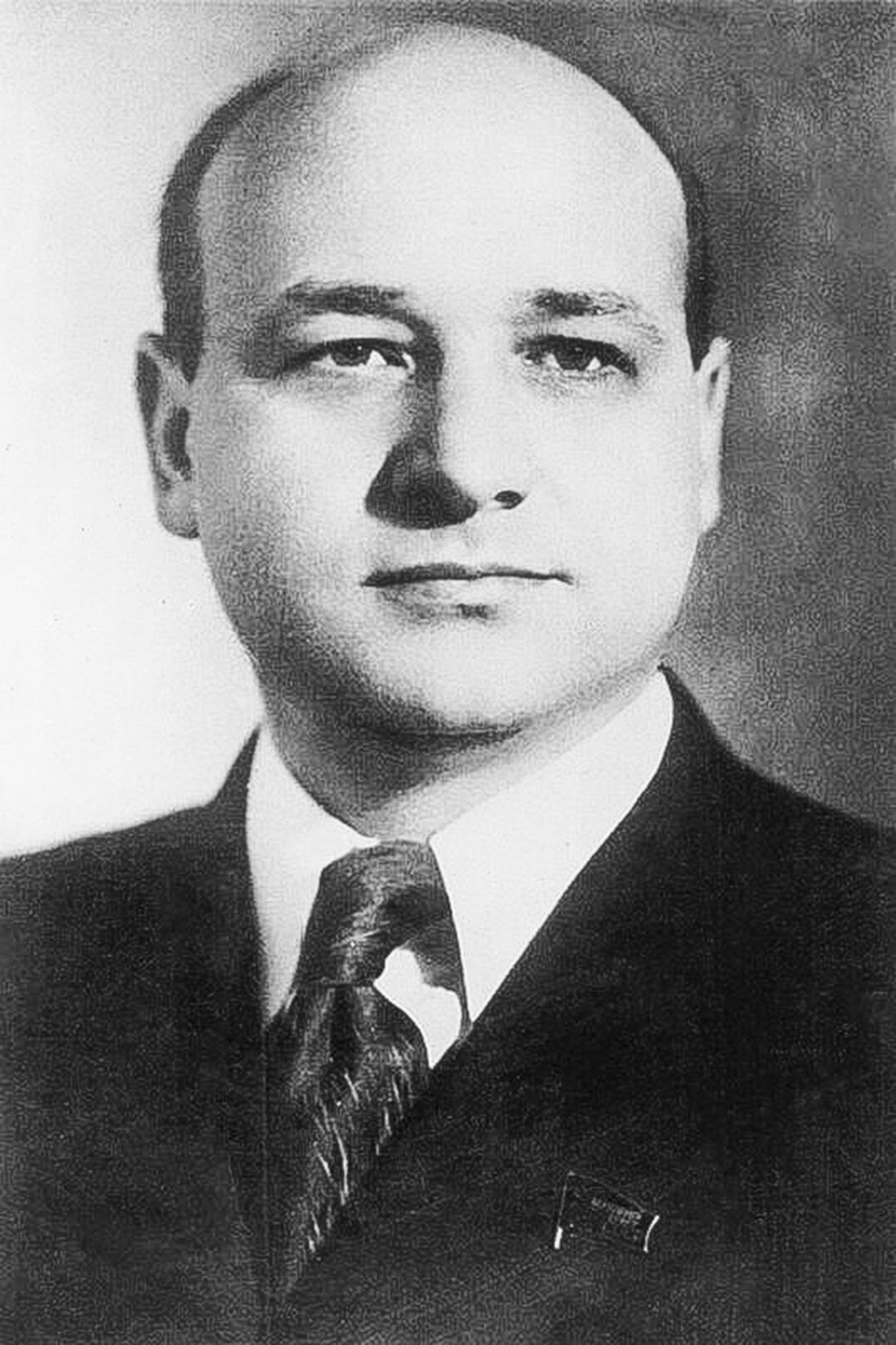

Eduard Streltsov was a Soviet football player and a forward for Torpedo Moscow FC. Debuting internationally at the age of only 18, Streltsov was a highly skilled player, who went on to score the fourth-highest number of goals for the national team.

Shortly before the 1958 World Cup, the bright career of the young football star was derailed, when Streltsov was accused of raping a woman at a party.

According to the prosecution, Streltsov and his friends were having a party at a dacha and got acquainted with young women, who joined their party. Allegedly, Streltsov had sex with one of them, a woman named Marina Lebedeva.

Lebedeva’s mother called the police the next day when her daughter had returned home. Streltsov was arrested and accused of raping the woman.

Although the evidence against Streltsov was inconclusive, the athlete confessed, as he was allegedly promised he would be able to keep playing football if he had admitted his guilt. Despite the promise, the court has sentenced the rising star to 12 years in prison.

The sentence sparked all sorts of rumors, such as it being a ploy of a competing football club or a personal vendetta of the young woman’s mother, who could have wanted Streltsov to marry her daughter. In any case, the Brazilian team won the World Cup in 1958 in Sweden and Pepé became the best young player in the championship. Being in prison, Streltsov didn’t have a shot at the title.

Streltsov was released on parole five years later and returned to his native football club, Torpedo Moscow. Surprisingly, he was also restored to the Soviet national team and was named the Soviet football player of the year in 1968.

After he died in 1990, Lebedeva was reportedly seen at Streltsov’s grave in 1997, where she laid flowers the day after the annual ceremony on the anniversary of his death.

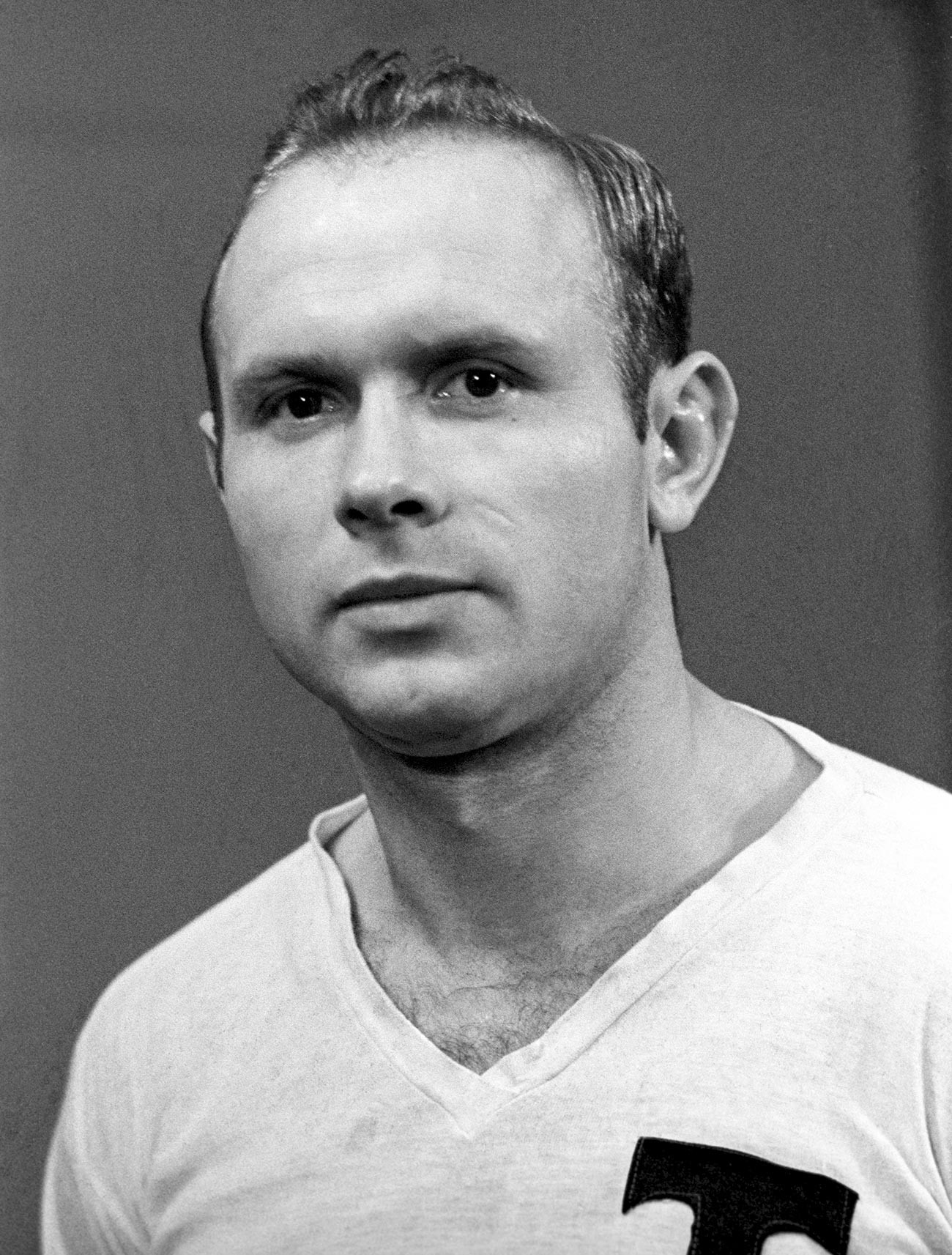

Boris Yeltsin give an interview to journalists.

Boris Kaulin/Gosudarstvennyy Istoricheskiy Muzey Yuzhnogo Urala /russiainphoto.ruIn September 1989, the political career of Russia’s future first president was gaining momentum: Yeltsin had won elections of people’s deputies in the Moscow electoral district and was heading the Committee of the Supreme Soviet on construction and architecture.

Only a month later, Yeltsin became involved in a juicy scandal that was widely discussed in the Soviet press.

The scandal began when Yeltsin came to a police station located in an area of government dachas, his clothes soaked and covered in mud. He explained to the policemen that he had been abducted by men in a car, who then threw him into the Moscow River from a bridge. Surprisingly, Yeltsin also asked the policemen to keep the story between them.

Despite the promise, the police officers reported the incident and the Soviet leadership caught wind of a political scandal that could have been used to discredit Yeltsin and derail his political career.

Mikhail Gorbachev demanded an investigation of the abduction, probably hoping the abduction had never happened and that the investigation would reveal Yeltsin’s dark secret, perhaps a mistress.

Mikhail Gorbachev demanded an investigation of the abduction.

Sergei Guneev/SputnikIndeed, the investigation had shown that Yeltsin’s story did not hold up: Had he been thrown off the said bridge into the river at the place he had pointed, he would have sustained severe injuries as the bridge was too high and the river too shallow. Yeltsin’s driver also refused to corroborate Yeltsin’s story. On top of that, a bouquet was recovered at the scene.

Although there was nothing criminal in Yeltsin’s behavior that night, his political opponents used the scandal to discredit the politician. In turn, Yeltsin dismissed the accusations and rumors: “A special meeting in the KGB was held to give instructions to spread rumors that Yeltsin was somewhere drinking, was going out with women. They crossed all the lines when anger eclipsed their reason and reasonable actions. Their bitterness has no limits, it has already turned into clear harassment aimed to compromise, discredit the Deputy who has long been, so to speak, like a bone in their throat, which sticks out, you know, like a nail.”

Genuine or not, the incident was not enough to topple Yeltsin’s political career and the then-deputy assumed the highest office of newly independent Russia only a few years later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox