Exchange students from the German Democratic Republic in Moscow, 1979.

Alexander Chumichev/TASSHigher education in the Soviet Union was free for everyone. However, prospective students had to pass entrance exams to enroll. Since higher education was so accessible, competition was very high. Enrolment commissions of the best universities in the USSR (often located in Moscow) crushed the hopes of many young people who had hoped to enroll in a university and “conquer” the city.

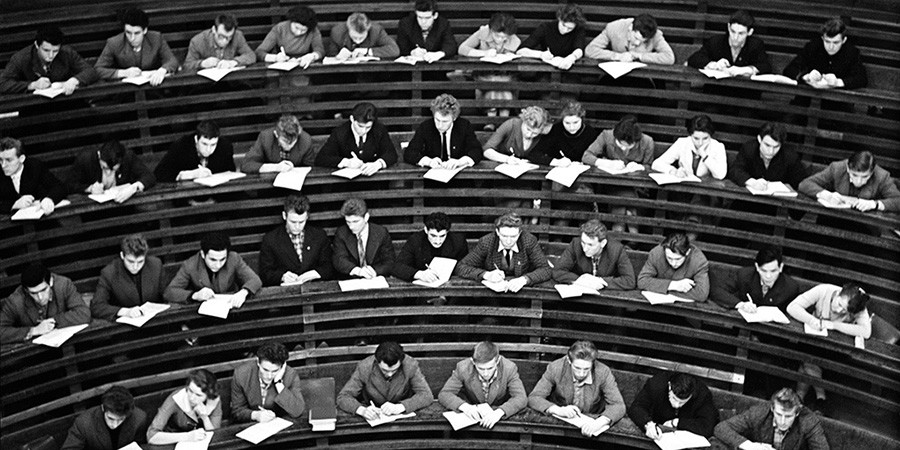

Students in an auditorium, 1967.

Yuri Abramochkin's archive/russiainphoto.ru

Students during freshmen day at the Moscow Institute of Electronics and Mathematics, 1976.

Pavel Sukharev's archive/russiainphoto.ruStudents received a monthly allowance that varied depending on their academic performance: the better an academic record, the bigger the allowance. The money was allocated from the budgets of the state-sponsored universities.

Although the sum varied from university to university and from one individual student to another, in general, it was enough to cover accommodation in a dormitory (that was extremely cheap), pay for food, transportation and a few available entertainments like cinema or sports.

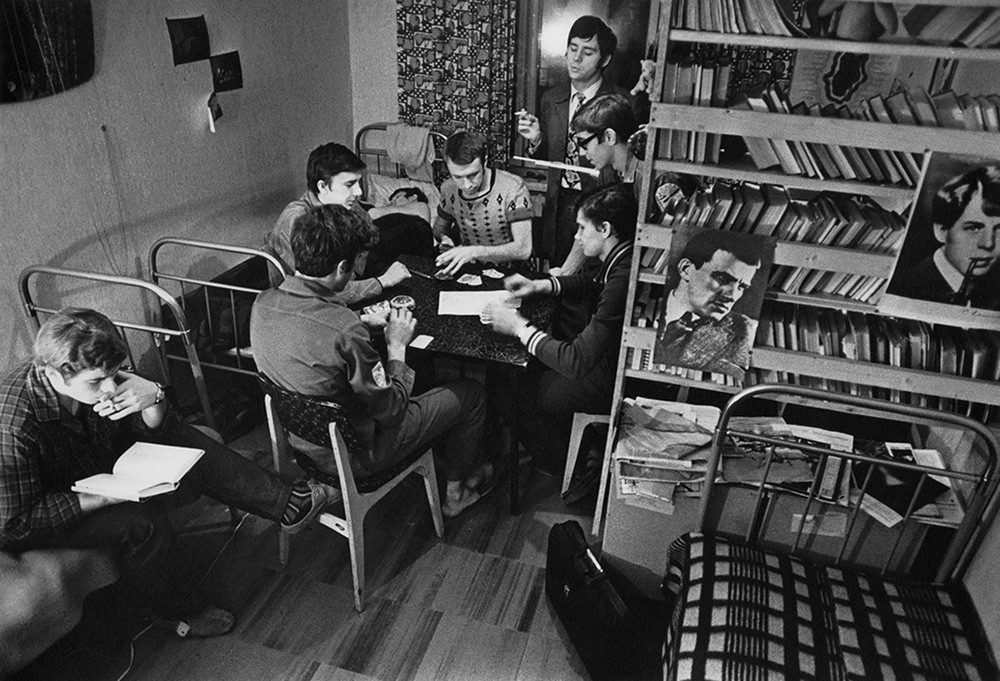

Students at the Moscow State University dormitory, 1963–1964.

Vladimir Lagrange/МАММ/MDFNonetheless, many students picked odd jobs to earn more money. They worked as assistants at their universities’ departments, tutored fellow students for cash, traded in foreign-made cigarettes, jeans and other scarce capitalist items, or worked as janitors.

Students conduct experiments in the laboratory at the Moscow Institute of Steel named after Joseph Stalin, 1942.

Ivan Shagin/МАММ/MDF“I liked wasting money so I worked as a lab assistant. I received 55 rubles a month for 2-3 hours of work per day. My monthly allowance was 50 rubles [paid by the university]. That is I had as much as 70 rubles left every month after deducting my daily expenses. Do you know what you could buy for 70 rubles? A week’s vacation in Crimea!” wrote journalist Yuri Alexeev about his student years in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Students relax in a club-cafe after day’s work. Moscow, 1978.

Pavel Sukharev's archive/russiainphoto.ruPerhaps the most appealing feature of higher education in the Soviet Union was that graduating students were guaranteed employment. The state took care of creating as many jobs as were needed for all graduating students every year. The practice that appears impractical in modern conditions was feasible then, due to the planned-economy in the USSR and rapid industrialization and urbanization that happened in the USSR in the 20th century.

Senior students in the laboratory of spectral analysis. Chelyabinsk, Russian SSR, 1954.

The State Museum of the South Ural HistoryA great chunk of majors that the Soviet universities offered were in natural science and engineering: the state prioritized hard skills over humanities, although many majors in humanities — in various art, theater, history schools — were also available.

Students in an art studio in 1935-1940.

Ivan Shagin/МАММ/MDF

Korean delegates at the Moscow Choreographic School of the Bolshoi theater of the USSR, 1949.

Semen Mishin-Morgenshtern/МАММ/MDF

First-year students in a sculpture workshop in Moscow, 1969.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/МАММ/MDFAt the peak of industrialization in the USSR, the state saw university students as a formidable labor force that could be used on a mass scale. In 1959, the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League (known as ‘Komsomol’) organized university students into newly formed ‘student construction brigades’. Members of the brigades traveled throughout the Soviet Union to work on construction sites during academic breaks. Although this extracurricular activity often involved hard manual labor and a good effort of engineering genius, many students saw it as an opportunity to travel and advance their career prospects.

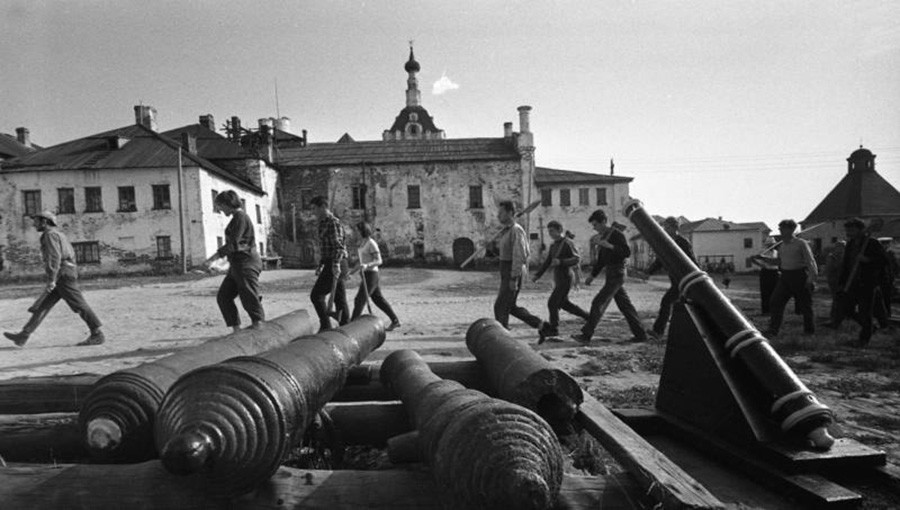

Members of a student construction brigade of the Moscow State University, 1967.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/МАММ/MDFMany students were also recruited to work on fields: pick up potatoes, grapes, or cotton, depending on the particular Soviet republic where they worked. This job was not paid and students were sometimes coerced into participating with threats of expulsion from the Komsomol: something that could have undermined their standings at universities and future careers. After a day of work, students would shelter in nearby dormitories, play musical instruments, read books, socialize and, sometimes, fall in love — something that made the days of hard labor a more enjoyable experience.

Students travel to work in the fields in Kazakh SSR, 1952.

Arkady Shaikhet/МАММ/MDF

Students in the fields in Kazakh SSR, 1952.

Arkady Shaikhet/МАММ/MDF

Students work on a cornfield in Tambov Region, 1957.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/МАММ/MDFDuring an academic year, students entertained themselves with student activities that were similar from one academic establishment to another. Students played musical instruments and vocalized, arranged theater performances and staged comedy shows known as ‘KVN’ — “Club of the Funny and Inventive”. Creative student groups by and large filled the void in underdeveloped Soviet home-made show business. Many of the notable student performers built formidable careers on Russian TV after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Students perform on stage in Moscow, 1955.

Sokolniki Park

Students play music by a campfire. Altai, 1957–1963.

Sigismund Kropiwnicki/МАММ/MDFSports was a popular past-time among students, too. These are students of the Institute of Physical Culture at the Dynamo stadium in Moscow in 1936.

A coach of the women's volleyball team with his students in the city of Kurgan, Russia, 1952.

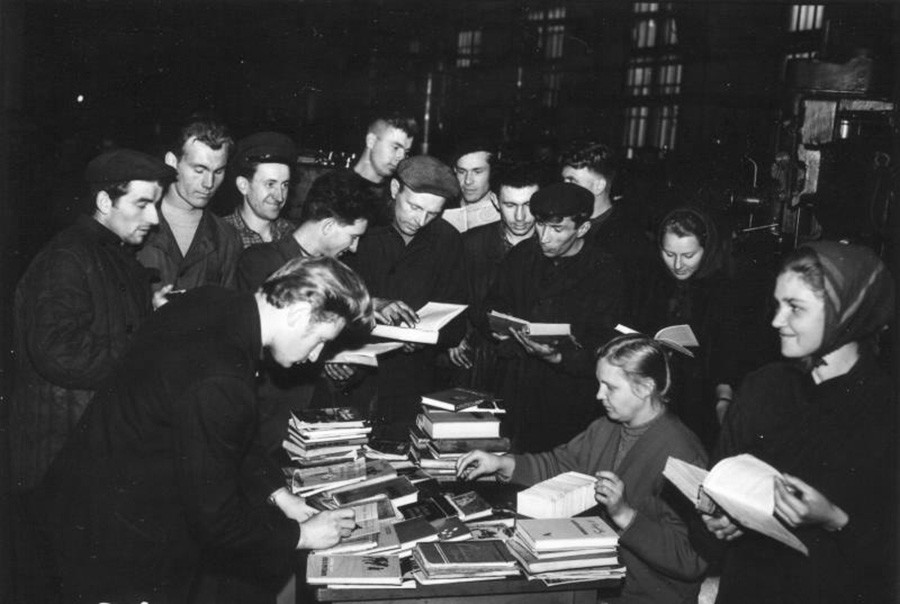

Yeltsin CenterRadio and books were also a popular form of entertainment for Soviet students. Book clubs provided a space where students socialized and chased rare books and radio was a source of information and music. Yet, both of these media also provided a space for students to get politically involved: some students tried to listen to Western radio channels like the Voice of America and secretly debated political matters in book clubs.

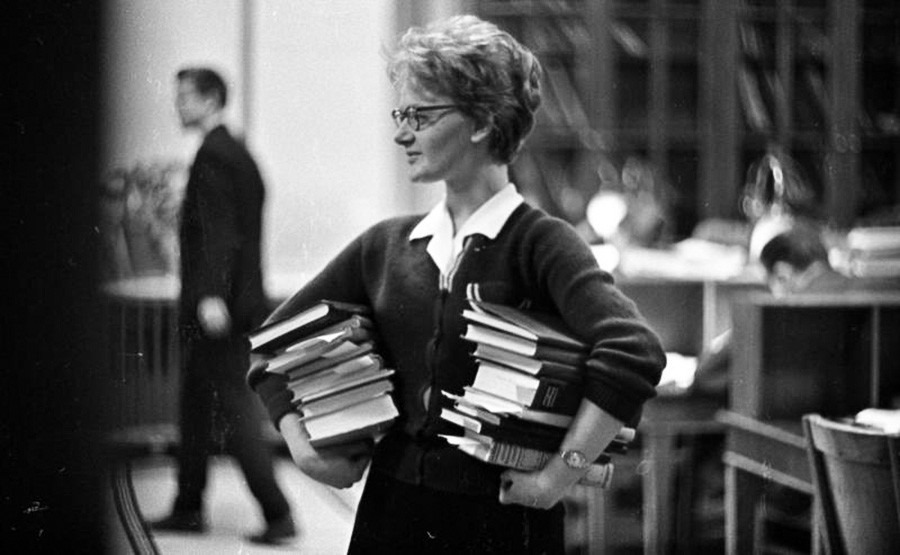

Students carry books, Yerevan, Armenian SSR, 1959.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/МАММ/MDF

Book distribution, 1960–1965.

МАММ/MDF

A student with books, 1963–1964.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/МАММ/MDF

The sixth World Festival of Youth and Students, held in Moscow in 1957.

Mikhail Trakhman/МАММ/MDF

A great many students from other countries visited the Soviet Union during the festival in the summer of 1957.

Sergei Vasin/МАММ/MDF

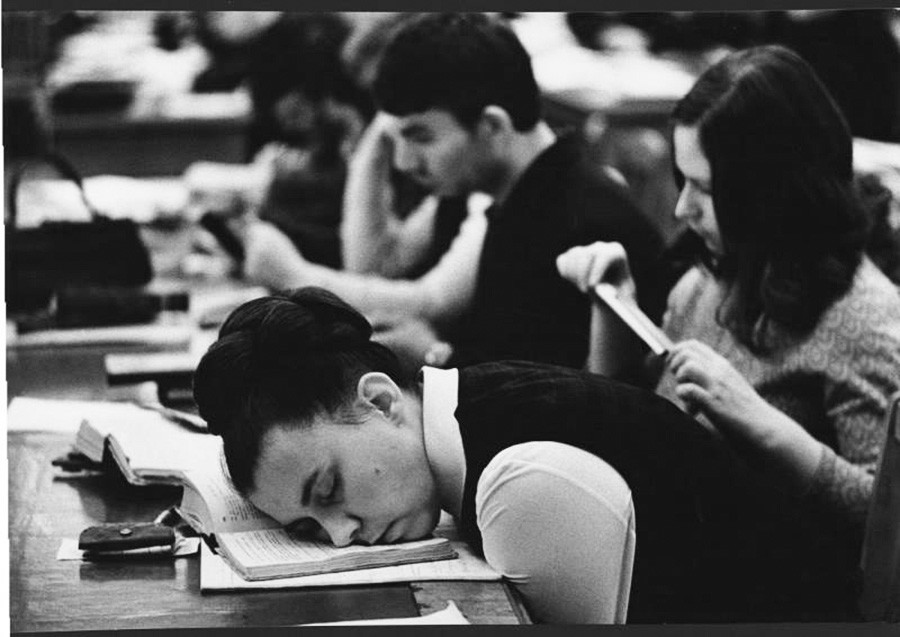

A student falls asleep during class, 1972.

Vsevolod Tarasevich/МАММ/MDFIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox