Before Neil Armstrong stepped on the Moon in 1969, the Earth’s satellite remained a mystery to humankind. Even more so, its “dark side”. dubbed “dark” because it is permanently hidden from view from Earth, the far side of the Moon was yet another object of desire to pioneers of space programs in the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Back in 1957, when the Soviets launched the first artificial Earth satellite — Sputnik 1 — into space, this event marked a very important milestone for space exploration. Nonetheless, people around the world found it hard to believe that humankind could advance even further and observe the far side of the Moon any time soon.

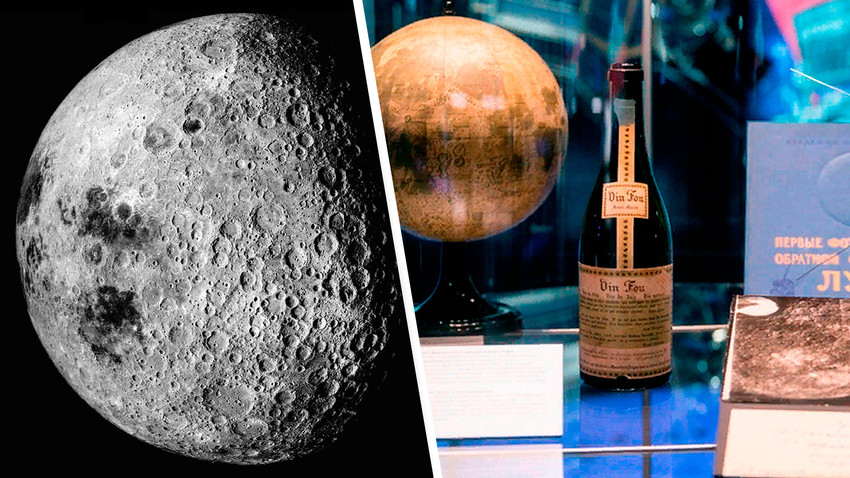

The prospect appeared so distant, yet so captivating, that one French winemaker, Henri Maire, publicly announced he would grant 1,000 bottles of champagne from his own reserves to anyone who would be able to see the far side of the Moon.

Ironically, Soviet scientists were already working on this.

The mission to photograph the far side of the Moon was led by Sergei Korolev, the father of Soviet cosmonautics and the mastermind of most of the groundbreaking Soviet achievements in space exploration.

Sergei Korolev, the father of Soviet cosmonautics and the mastermind of most of the groundbreaking Soviet achievements in space exploration.

Public domainThe plan was relatively easy: to launch a cylindrical canister — a space probe — into space towards the Moon and let the gravity do the rest. The space probe was equipped with cameras, a photographic film processing system, batteries, a radio transmitter, a gyroscope to maintain orientation and angular velocity and a few fans for temperature control.

The device had no rocket motors to use for course corrections, as scientists relied on Moon’s gravity instead to help them conduct the so-called ‘gravity assist maneuver’: according to the plan, the space probe was supposed to travel to the Moon and once caught by the Moon’s gravity, pass behind the Earth’s satellite from south to north and sling back to Earth.

The space probe going to the far side of the Moon was dubbed ‘Luna-3’. Surprisingly, the most challenging part was not calculating the orbit of the Moon or the satellite, but to manage equipment and staff on the ground.

The signal from Luna-3 was received by a radio antenna mounted on top of a mountain peak in Crimea. To Korolev’s despair, local staff reported communication problems: Luna-3 did not receive some of the commands from Earth. The chief ordered his team to follow him to Crimea to urgently mitigate the situation.

Once the all-powerful Korolev arrived in Crimea he took matters into his own hands and implemented unprecedented measures: At his orders, the ships of the Black Sea fleet were to cease all communications, while a dedicated boat was set to cruise the Black Sea looking for and suppressing possible sources of radio interference and the traffic police were to block the roads near the observatory.

These measures helped improve the signal, but a new problem arose. To his surprise, Korolev learned that the observatory might not have enough magnetic film to record images of the lunar landscape.

A cinematic recreation of the moment when the Soviet scientists photographed the dark side of the Moon.

D. Gasyuk/Sputnik“Sergei Pavlovich [Korolev] was furious. I understood him. After all, if we had been warned, we could have brought this scarce film with us from Moscow,” wrote academician Boris Chertok who assisted Korolev during the launch.

Ironically, the film was so scarce, because it was extracted from downed American reconnaissance balloons that had spied over the USSR. This film was of unprecedented quality unmatched by the Soviet industry.

Infuriated, Korolev ordered the additional films to be delivered to the observatory from Moscow by plane and then by helicopter.

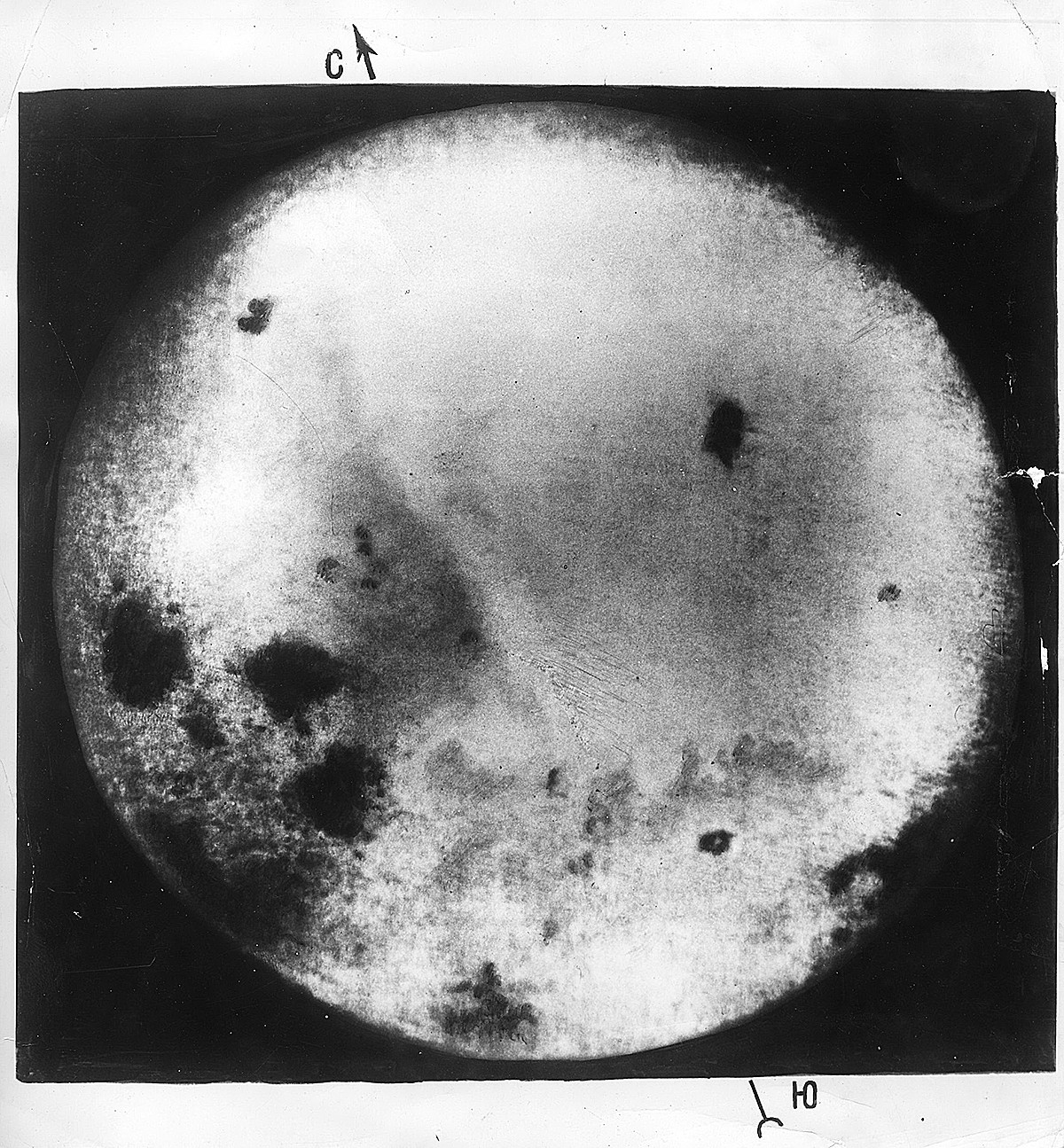

Early morning on October 7, 1959, the team of Soviet scientists waited with bated breath as Luna 3 approached the Moon. Suddenly, the first image began appearing on paper.

A mockup of the Soviet automatic interplanetary station Luna-3.

Alexander Mokletsov/SputnikThe designer responsible for receiving the data looked at the paper and, to the shock of others, tore the first-ever made photo of the far side of the Moon to pieces. The image quality was not good and he was ready to gamble the next photos would be better.

One of the first photographs of the far side of the Moon the Luna-3 took.

SputnikTo everyone’s relief, the following photos were indeed of much better quality. Korolev took the first photograph of the far side of the Moon of decent quality and inscribed a line: “The first photo of the reverse side of the moon that shouldn’t have turned out.” He signed it and dedicated the photo to the director of the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory Andrei B. Severny.

Soviet postal stamp dedicated to photographing the dark side of the moon.

Public domainYet again, the Soviet science triumphed. The Soviets proceeded to name newly discovered geographical objects on the Moon while the photographs of the dark side of the Moon were published on the front page of the Soviet newspaper Pravda and the news resonated around the world.

In another part of the world, French winemaker Henri Maire read about the Soviet achievement and admitted he had lost his own bet. Mere sent 1,000 bottles of champagne by post to the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

The Academy’s president ordered the bottles to be delivered to the team who worked on the Luna 3 project. “We had the honor of receiving several dozen bottles of champagne from the warehouse of the Academy of Sciences. You will get a couple of bottles, the rest will be distributed among the apparatus and other non-participants,” Korolev told his staff.

Years later, when Korolev’s daughter Natalia Koroleva, caught wind of this anecdote, she made it her mission to locate at least one bottle of the champagne. It turned out, Korolev’s former secretary had one bottle preserved though emptied.

Today, a miniature replica of Luna 3 and the bottle can be observed at the Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox