The candidates had to undergo rigorous tests and strenuous training. 20 would-be cosmonauts were performing feats of physical training. The challenge was to test the limits of the Soviet pilots, including mental preparation and cardiovascular conditioning.

The potential candidates were found among fighter pilots who had typically experienced a G-force similar to that what was expected during a space flight. The main qualifying criterion was the cosmonauts’ physical condition.

Father of the Soviet space program Sergei Korolev (the aerospace designer who helped launch the first man into space) believed that an ideal aspirant should be around 30 years of age; 5 feet 7 inches tall (1.70 m) and weighing 70 kg (154 pounds).

After lengthy tests, the list of twenty candidates was eventually narrowed down to five.

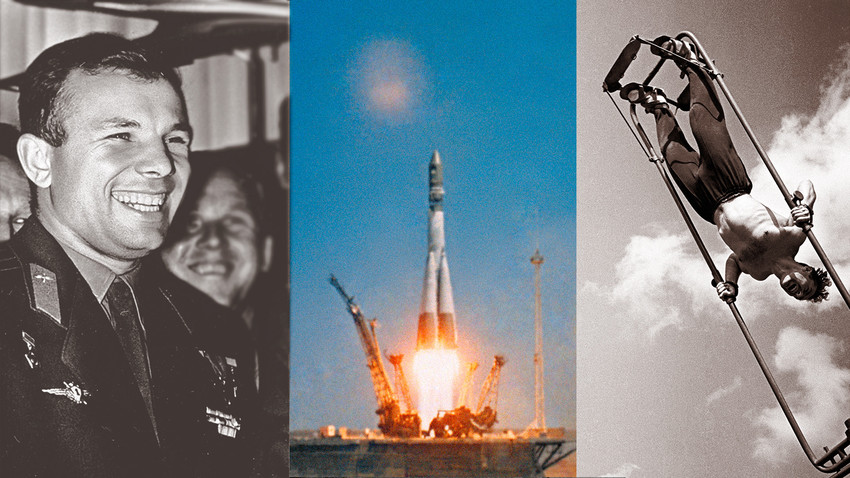

Gherman Titov at the astronaut training facility in Star City near Moscow in 1960.

Alexander Sergeev/SputnikTitov was Gagarin’s closest rival. “He was trained as well as I was and was probably capable of even more. Maybe they didn’t send him on the first flight, because they were saving him for the second, more difficult flight,” Gagarin later recalled in his book, ‘The Road to Space’.

The two heroes, Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov, in 1961.

Snegirev/SputnikShortly after Gagarin’s pioneering flight, Titov was blasted into space from the Baikonur cosmodrome in the Kazakh SSR. The 25-year-old entered the history books as the second man in orbit and the first who managed to stay in space for more than 24 hours.

READ MORE: 10 little known facts about Gagarin's iconic space flight

Gagarin’s flight lasted “only” 108 minutes and those behind the Soviet space program expected the next voyage to last longer. Despite doctors fearing the worst, Sergei Korolev insisted that only a 24-hour flight could give scientists some new insights into the space environment and human beings.

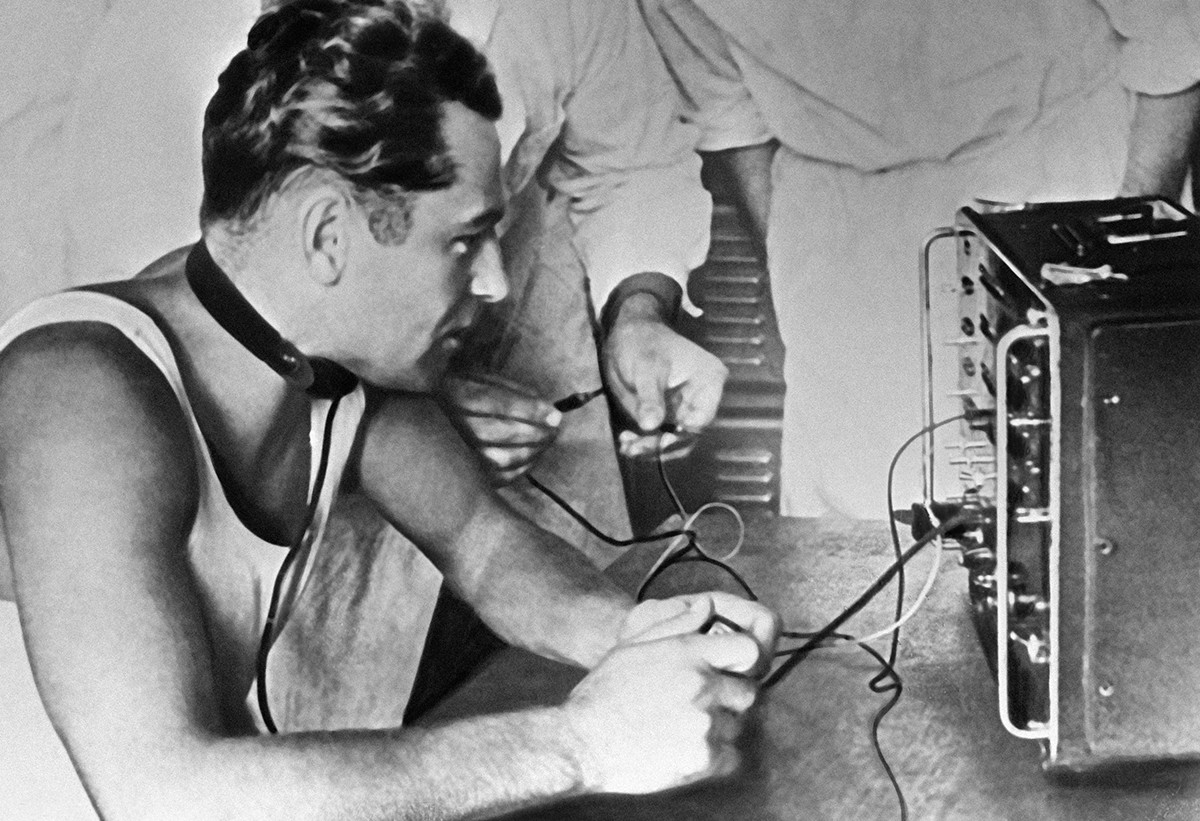

Gherman Titov receiving training in 1961.

SputnikTitov fulfilled that in August 1961, riding his Vostok-2 capsule for 17 orbits and spending a total of 25 hours in space.

Bondarenko was selected to become a cosmonaut in 1960, valued for his athletic prowess and endearing personality. He worked very hard to prove his worth. Unfortunately, the youngest member of the cosmonaut corps proved to be the unluckiest of all, instead. An irreversible tragedy occurred on March 23, 1961, just several days before Yuri Gagarin’s scheduled flight.

Part of the cosmonauts’ routine training took place in a special isolation chamber, the so-called “Chamber of Silence”. It was akin to a monk’s cell, boasting basic toilet facilities, a narrow bed, a table and a seat similar to the one they would have in the Vostok capsule. The tiny cell, where the cosmonauts had to spend 10 days, was pressurized to imitate the environment in space, with an unusually high concentration of oxygen.

Valentin Bondarenko was selected to become a cosmonaut in 1960.

Altay State Memorial Museum of Gherman Titov.Bondarenko went through all the testing, and was on his way to leaving the chamber when the tragedy unfolded. Bondarenko received the last go-ahead to remove his biomedical sensors, however that’s when he made a fatal error. The cosmonaut wiped the adhesive off with rubbing alcohol on a cotton pad. On the spur of the moment, he threw it away, with the pad landing right on the hot plate’s coil. A fire broke out, spreading fast, due to the extremely high concentration of oxygen. “I’m so sorry,” the severely burnt Bondarenko whispered as he was rushed to the Botkin hospital in Moscow.

Doctors were unable to save his life. The 24-year-old died from shock eight hours later. The incident was kept secret for a long time. The name of the deceased cosmonaut wasn’t mentioned in the official chronicle, with his face removed from group photos featuring other members of the first crew.

In the early 1950s, Rafikov, born in Kyrgyzstan to a Tatar family, graduated as a pilot from the local military aviation school and served at an air defense unit.

His peers were sure that Mars Rafikov would be one of the first to go into space.

At the ripe age of 26, the man, aptly named Mars, suddenly had a run of luck and was selected for the first astronaut corps, along with Yuri Gagarin. Rafikov, who was being trained for the launch aboard the Vostok 1, went through intensive training and was doing just fine, it seemed. His peers were 100 percent sure that Mars would be one of the first to go into space.

Members of the first group of Soviet cosmonauts in 1961. Second row (left to right): Alexei Leonov, Andriyan Nikolayev, Mars Rafikov, Dmitry Zaikin, Boris Volynov, Gherman Titov, Grigory Nelyubov, Valery Bykovsky, Georgy Shonin.

SputnikHowever, things took a turn for the worse. According to Rafikov, his love life was to blame. He split with his wife and was planning his divorce when his bosses became worried about his family status. Rafikov was told to salvage his marriage for the sake of his image, but Mars wouldn’t listen.

In 1962, the aspiring cosmonaut was removed from the crew. The official reason was Rafikov’s absence without permission to leave his unit. Mars believed he was dismissed because of his refusal to comply with the wishes of the authorities.

After his discharge, Rafikov went back to being a pilot. In 1980, he acted as an air observer in Afghanistan and was awarded the USSR’s top Order of the Red Star.

Of the twenty men who became part of the first crew, eight fell by the wayside. Some couldn’t make it, due to health issues; others suffered from bouts of bad temper and impatience and were eventually discarded.

Grigory Nelyubov was poised to become the third Soviet cosmonaut in space.

Altay State Memorial Museum of Gherman Titov.Grigory Nelyubov was one of the first to join the historic crew. He was Gagarin's second backup and was poised to become the third Soviet cosmonaut in space. His flight was scheduled for the fall of 1961. However, at the last minute, it was decided to send several cosmonauts into space, instead of just one. This reroute probably cost him a step that eventually thwarted Nelyubov’s career.

In 1963, Nelyubov and two of his colleagues were detained in a Moscow cafe. Grigory was drunk and fairly rude when speaking to the law enforcement officers. Police reported the incident directly to Soviet aviator Nikolai Kamanin, who had recruited and trained the first generation of cosmonauts, Yuri Gagarin and Alexei Leonov among them. Nelyubov was asked to apologize but refused and was immediately expelled from the crew.

He made several attempts to come back, as Korolev still had faith in him. But, after his mentor’s death in 1966, that door slammed shut behind Nelyubov forever. Shortly after, in a tragic twist of fate, Nelyubov was fatally hit by a train.

Some people know the value of waiting better than others. They are usually either astronauts or cosmonauts. Boris Volynov is a perfect example of how good things come to those who wait. He is also the last surviving member of the original group of cosmonauts.

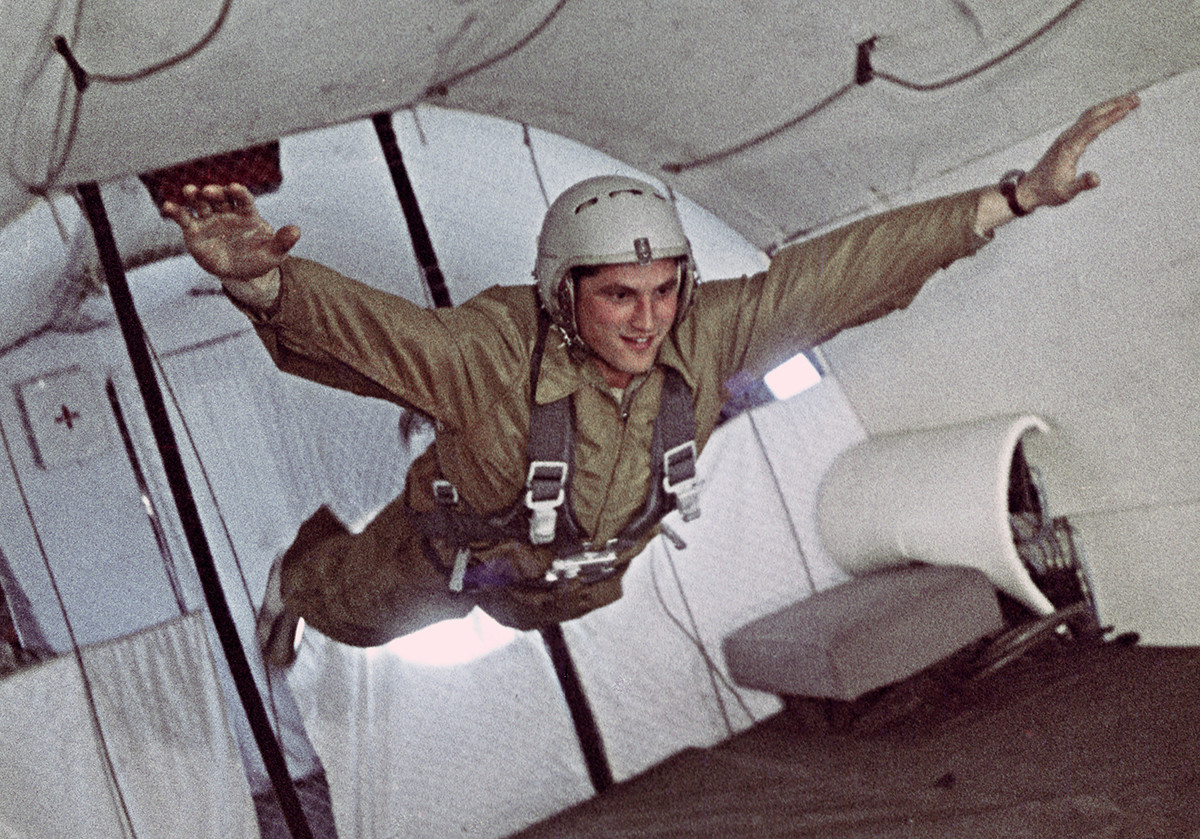

Boris Volynov enjoying the weightlessness of space during training in 1965.

SputnikREAD MORE: Why do they call astronauts ‘cosmonauts’ in Russia?

Volynov dreamed of becoming a pilot since he was a little boy. Like several others, Boris became a member of the first cosmonaut crew on the same day as Yuri Gagarin. He underwent training with the cosmonauts of Vostok 3 and Vostok 4 and was a backup crew member for Valery Bykovsky, who flew into space aboard the Vostok 5.

Test on the bicycle ergometer in 1968.

SputnikIt seemed like Volynov finally got things rolling in 1965, when he was appointed commanding officer of Voskhod 3. However, that mission was cancelled a year later in favor of the 22-day unmanned test flight of Kosmos 110, with two dogs on board, Veterok and Ugolyok.

READ MORE: Animals in space: What does it take to be tasked with exploring the Universe before humans?

His luck finally came along in 1969, when Volynov spent three days aboard the Soyuz 5, becoming the first Jewish cosmonaut. After seven years of waiting, his next flight took place in 1976. The Soyuz 21 mission lasted 49 days, 6 hours and 23 minutes.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox