The first and only U.S. military intervention in Russia began on May 27, 1918, when the cruiser USS Olympia arrived in Murmansk, which was already under British control. Several months later, 5,500 soldiers of the U.S. Army disembarked in another Russian port, Arkhangelsk (which translates as “Archangel”). At about the same time, another 8,000 U.S. servicemen arrived in the Russian Far East.

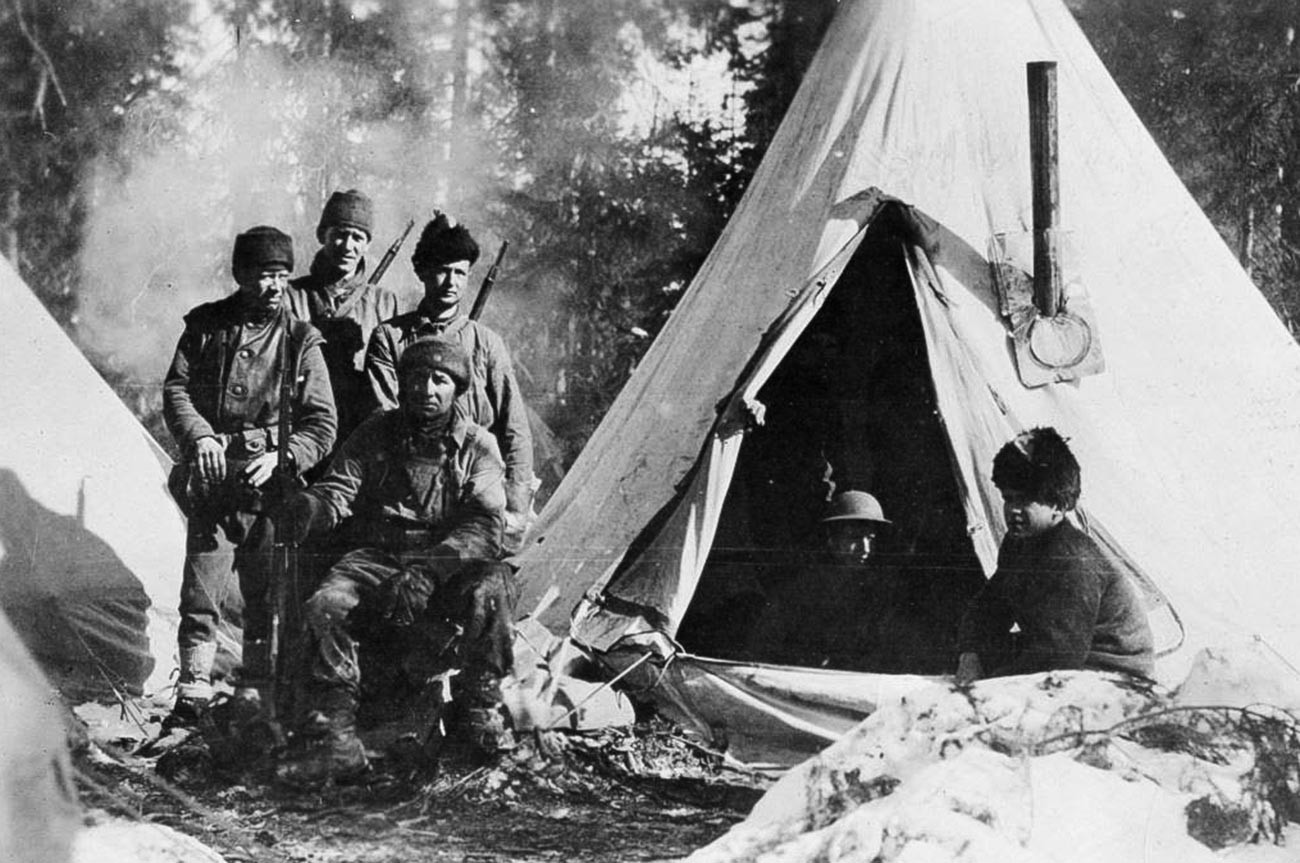

American troops in Arkhangelsk, 1919.

Archive photoOriginally, the large-scale intervention by the United States and Entente powers in the Civil War in Russia was not prompted by their hatred of Bolshevism. Far from it. The main reason was the conclusion of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918, between the Soviet government and the Germans, which ushered in Russia’s withdrawal from the war and the effective collapse of the Eastern Front. The German Empire could now direct all its remaining might on France, spelling big problems for the Allies. The Bolsheviks were not viewed by the Entente as a real force capable of holding on to power for long. They were regarded as German puppets and stooges of the Kaiser acting in his interests.

German and Soviet soldiers in 1918.

Archive photoAt the official level, it was declared that the main mission of the U.S. soldiers would be to protect American military supplies which had been sent to Russia before the Revolution and had not yet reached the Bolsheviks. Washington feared that the latter would hand them over to the Germans. Also, the Americans were to assist the so-called Czechoslovak Corps (Legion) leave Russian territory. The corps had been formed in October 1917 by the Russian military command and was composed of Czech and Slovak prisoners of war who had volunteered to fight against Germany and Austro-Hungary. Legally, it was under French command. The legionaries were to be evacuated to the Western Front via the Far Eastern ports. However, in the spring of 1918, when the Bolsheviks tried to disarm them, they revolted and took control of large areas of Siberia.

Units of the Czechoslovak Corps in Irkutsk.

Archive photoThe U.S. officially stated that it did not contemplate “any interference of any kind with the political sovereignty of Russia, any intervention in her internal affairs, or any impairment of her territorial integrity either now or hereafter”. In practice, its military contingents were supposed to help the White movement to win the Civil War after the latter declared its intention to continue the war with the Germans. However, neither the U.S. nor any of the other interventionist powers planned to lose their own men on foreign soil and were intent on shedding as little blood as possible. “The Allied troops, however, had no instructions about taking part in operations and arrived with a completely vague set of objectives,” Ivan Sukin, the foreign minister in the government of Alexander Kolchak, the leader of the White movement in the east of the country, wrote in annoyance.

The U.S. troops in Khabarovsk.

Archive photoThe American Expeditionary Force in Siberia (8,000 soldiers) under Maj. Gen. William S. Graves was entrusted with protecting sections of the Trans-Siberian Railway and the coal mines of Suchan (Partizansk). Formally, it was subordinated to the French general Maurice Janin, who was in overall command of the allied interventionist forces in the Far East. The Americans weren’t at all interested in the Czech legionaries, as publicly stated, but in their own allies in the intervention, the Japanese. Having sent over 70,000 of its own soldiers to the Russian coastal region as a member of the Entente, Japan was playing its own game, pretty much openly seeking to annex it. This could not but arouse the apprehensions of its Pacific rival, which used the Siberia force as a deterrent to Tokyo’s expansionism. Relations of neutrality verging on hostility developed between the Americans and the Japanese forces, as well as the White Cossack atamans subordinated to the latter, often leading to conflicts. Thus, Graves openly called Ataman Ivan Kalmykov a “murderer, robber and cutthroat” and the “worst scoundrel I ever saw or ever heard of”.

Hospital Car operated by the American Expeditionary Forces at Khabarovsk, 1919.

Archive photoThe nature of relations between the American troops and the local Red partisan detachments ranged from a desire to avoid each other, on the one hand, to brutal confrontation, on the other. The most serious clash between them occurred in the village of Romanovka on June 24, 1919, when the interventionists incurred 19 dead and 27 wounded in a battle with the detachment of Grigory Shevchenko. In response, an anti-partisan operation was mounted in which the Bolsheviks were pushed deep into the taiga.

American soldiers distribute food to the prisoners.

Archive photoIt became customary in the Soviet Union to believe that the American intervention force had actively participated in mass executions of local civilians. The Baikalsky Rabochy newspaper wrote in its issue of June 10, 1952, that 1,600 Soviet citizens had been shot by White Guards and Americans in the Tarskaya ravine in the taiga on July 1, 1919. “The corpses of those who had attempted to flee lay next to the grave itself for several days. A doctor from the American Red Cross prevented the bodies of the slain from being buried for three days,” the newspaper wrote, quoting the words of an eyewitness to the slaughter by the name of Bolshukhin. Today, however, the allegations of the involvement of American troops in acts of mass terror are seen as questionable, even though individual cases of war crimes against civilians did occur.

A Bolshevik shot by an American guard.

Archive photoThe principal role in the U.S. intervention in northern Russia, known as the ‘Polar Bear expedition’, was played by the 339th Regiment under Col. George Stewart. It was composed of men from the northern American state of Michigan. It was felt that, accustomed as they were to cold weather at home, they would rapidly acclimatize to the harsh climatic conditions of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. Overall, command of the American troops (5,500 men) was exercised by the British, whose forces in the region were several times larger.

The U.S. captain with a trophy Bolshevik saber.

Archive photoIn northern Russia, unlike the Far East, the Americans found themselves fighting the Bolsheviks on quite a large scale. While Graves’ “Siberians” were stationed deep in the rear of the Kolchak army’s positions, the ‘Polar Bears’ were involved in direct clashes, not just with partisan detachments, but also regular Red Army units. In the course of a 6th Army advance near Shenkursk in January 1919, up to 500 American soldiers found themselves surrounded. Losing 25 men, as well as artillery, equipment and ammunition, they only managed to break out with the help of White officers who knew the locality well.

American military engineers in Russia.

Archive photoThe signing of the armistice in November 1918 and then the peace with Germany in June 1919 placed a question mark over the usefulness of the American troop presence in Russia. “What is the policy of our nation toward Russia?” asked Senator Hiram Johnson in a speech on December 12, 1918. “I do not know our policy and I know no other man who knows our policy.” The army command were in no hurry to order an evacuation, however. A group of soldiers of the 339th Regiment who in March 1919 had submitted a petition asking to go home were threatened with court martial proceedings.

American soldiers in Russia, 1919.

Archive photoAfter the White movement was smashed in the north and east of Russia at the end of 1919, the presence of American troops there lost all purpose. The last soldiers left Russian territory in April 1920. During the entire period of the intervention, the Siberia Corps and the ‘Polar Bears’ lost 523 men, either killed in battle or dead through illness, frostbite or accident. Lt. John Cudahy of the 339th Regiment wrote in his book, ‘Archangel’: “When the last battalion set sail from Archangel, not a soldier knew, no, not even vaguely, why he had fought or why he was going now and why his comrades were left behind - so many of them beneath wooden crosses.”

American soldiers' tombs.

Archive photoIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox