The Battle of Galicia was decisive in the confrontation between Russia and Austria-Hungary in the initial phase of WWI. About 2 million soldiers and 3,500 artillery pieces on both sides fought it out along a 400km-long front.

The battle consisted of a series of separate engagements in which the Russians managed not only to halt the enemy advance, but to launch a major counteroffensive, resulting in the seizure of almost all of the historical region of Galicia and part of Austrian Poland. Having lost around 350,000 soldiers killed or captured — one third of its forces on the Eastern Front, Austria-Hungary suffered a blow that effectively incapacitated it until the end of the war. In virtually all subsequent major military operations against Russia, Vienna would have to rely on Berlin for assistance.

The rout of Austria-Hungary seriously undermined the significance of the German victory in East Prussia. Moreover, it improved the position of Serbia, which had been under intense pressure from Austro-Hungarian troops.

“The Russian successes in Galicia inflicted serious damage on the Austro-Hungarian armies, which proved fatal for the entire state organism of the dual monarchy,” wrote WWI participant and military theorist Alexander Svechin. “The Austrian troops, having initially gone into battle with gusto, were a spent force for the remainder of the war.”

Russian trenches in the forests of Sarikamish.

Public DomainIn late 1914, the 3rd Army of the Ottoman Empire fought hard to capture the Kars region (then part of the Russian Empire, today Turkey). A 90,000-strong force under Enver Pasha faced 60,000 troops from the Russian Caucasus Army and Armenian volunteer squads.

On December 29, the Turks completely surrounded the city of Sarikamish, the linchpin for both sides. Despite the enemy’s superiority, the Russian garrison put up fierce resistance, even managing to recapture the lost railway station and barracks, pushing the Turks out of the city.

Having failed to take Sarikamish, the 3rd Army suffered further heavy losses due to frostbite and lack of food — up to several thousand soldiers died a day. Soon the Russian troops launched a counteroffensive. This is how Major General Nikolai Korsun of the Russian Imperial Army, also a military historian, described the flanking maneuver by Colonel Dovgirt’s detachment into the rear of the Turkish troops: “Dovgirt’s column had to cover 15 km in a strong blizzard and very deep snow — deeper than the height of the average person, sometimes at a speed of only 2-3 km a day… when the column was already considered to have perished, it emerged from a gorge into the rear of the Turkish position.”

Russian poster depicting the Russian victory at the battle of Sarikamish.

Public DomainAs a result, the 3rd Army was utterly annihilated, with up to 80% of men killed, frozen, wounded or captured, against Russian losses of 26,000.

The success of Operation Sarikamish prevented a Turkish breakthrough to the Russian Caucasus. In addition, it greatly aided the British in Mesopotamia (Iraq) and the defense of the Suez Canal.

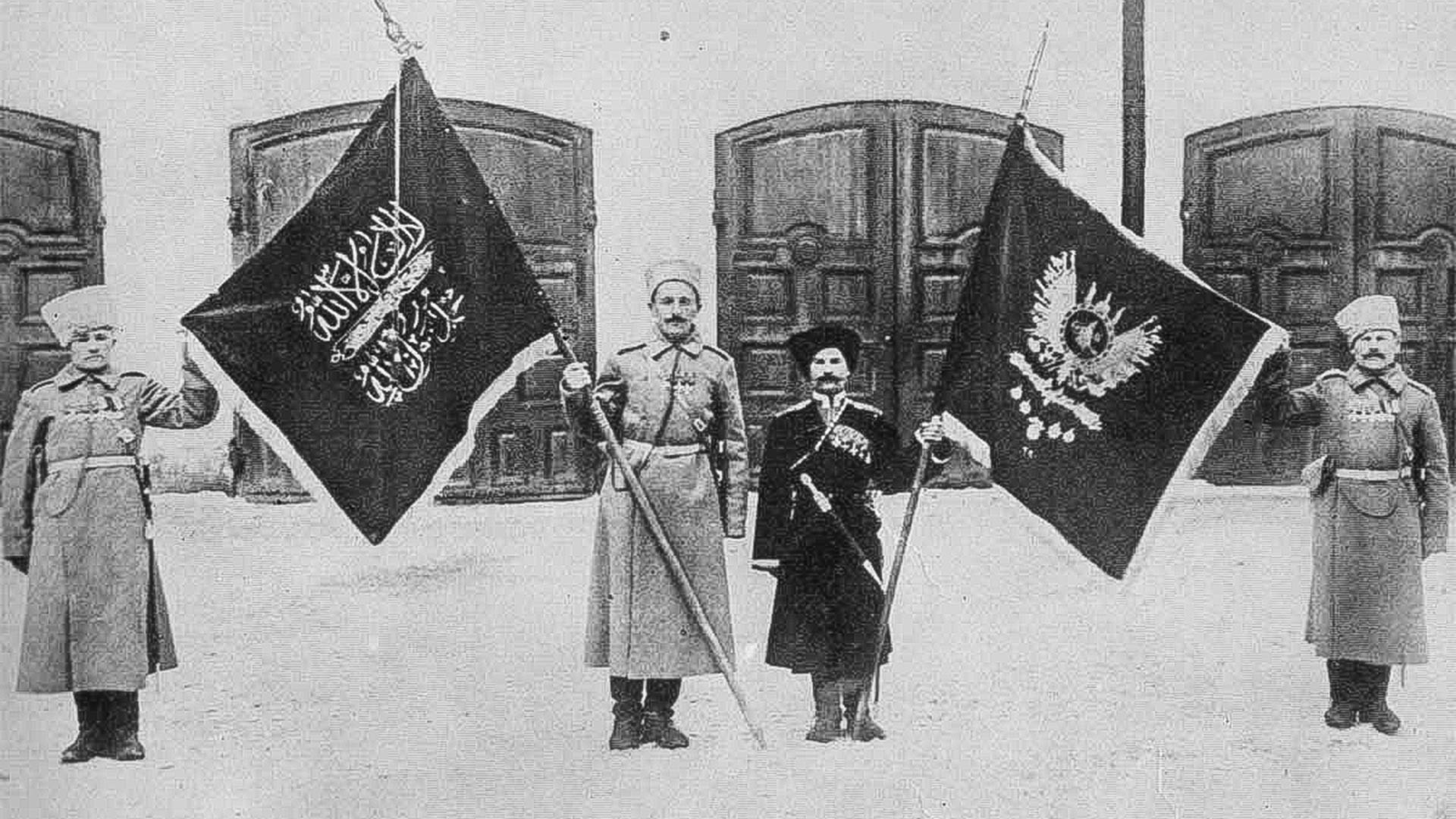

Russians with the trophy Turkish banners.

Public DomainAfter the Gallipoli fiasco in late 1915, the Allies began to evacuate their troops from the peninsula. For the Russian Caucasus Army, that meant the Turks could now concentrate all their forces on them.

Without waiting for the enemy to reploy its reserves from the Dardanelles to the Caucasus, the Russian troops went on the offensive. A 75,000-strong army under General Nikolai Yudenich faced 60,000 Turkish soldiers from the now familiar 3rd Army, reorganized and replenished after the defeat at Sarikamish.

The Turkish artillery gun, captured by Russians in Erzurum.

Public DomainThe Turks, believing that the Russians were preparing to celebrate Christmas and New Year, were caught completely off guard. Despite heavy snow and ferocious blizzards in the rugged mountain terrain, Yudenich’s soldiers overthrew the enemy, seizing the strategically important fortress of Erzurum.

The 3rd Army’s losses totaled more than 35,000, against several thousand suffered by Russia. The success of the Erzurum Offensive gave Russia the operational space to advance further into Anatolia.

General Brusilov.

Public DomainIn the spring and summer of 1916, the Russian military was preparing for a large-scale offensive in Europe. General Alexei Evert’s Western Front army group, which had a near double numerical advantage over the enemy, was due to deliver the main blow, with Alexei Brusilov’s Southwestern Front as an auxiliary force.

Brusilov’s troops were the first to advance, and their unexpected success made the offensive in this direction the priority. Although the Southwestern Front was slightly outnumbered by the enemy (534,000 against 448,000), it faced not the seemingly invincible Germans, but the far inferior and still demoralized forces of Austria-Hungary.

Deciding against a concentrated strike, Brusilov dispersed his forces in several directions. The tactic at first alarmed Nicholas II, now Russia’s commander-in-chief, but it soon became clear that the deeply echeloned enemy lines had been breached in several places at once. The Russian troops advanced 120 km deep, taking control of Volyn (part of Galicia) and Bukovina.

Ottoman troops in Galicia.

Public DomainAustria-Hungary was on the verge of defeat. Turkish divisions were even transferred from the Balkans to aid it. But in August the Russian offensive began to fizzle out. With the arrival of fresh German forces, it was halted entirely, giving way to sanguinary trench combat. In the final analysis, the Brusilov Offensive cost Russia up to half a million people, and the Central Powers lost more than a million killed, wounded or taken prisoner.

Despite the success of the operation (notwithstanding the casualty figures), Russia failed to break through the Carpathians and knock Austria-Hungary out of the war. The passivity of the other fronts, the indecisiveness of the General Headquarters, as well as the lack of coordination with Russia’s Western allies also played a negative role. As Chief of the General Staff of the German Army Erich von Falkenhayn wrote: “In Galicia, the most threatening moment of the Russian offensive had already been absorbed by the time the first shot was fired on the Somme.”

Nevertheless, the Brusilov Offensive significantly undermined the forces of Germany and even more so Austria-Hungary; it also saved Italy, which was on the verge of defeat, and eased the position of the French at Verdun. Inspired by Russia's successes, Romania entered the war on the side of the Entente. This, as it turned out, brought nothing but problems for the Allies, but that is a separate story.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox