There was no “maternity leave” for peasant women in Russian villages up until 1917 (and even then it was the first such decree in the world). During pregnancy they continued to work. “She does all the housework in the house, and in the field – digs and hoes, threshes, plants or digs potatoes, right up to the birth time,” wrote Olga Semenova (Tyan-Shanskaya), a 19th century Russian ethnographer. “Some women give birth while kneading dough. Some give birth in the field, others in a jolting cart (feeling the approach of childbirth, some women are in a hurry to get home).”

"A new acquaintance," 1885, by Kirill Lemokh (1841-1910)

Kirill LemokhRussians of the past married young. In the 16th-17th centuries, the age of marriage for boys was about 15, for girls – about 13. By the 19th century, peasants married at 18-20. And sadly, early pregnancies for these couples often ended in stillbirths – the girl’s young body couldn’t properly carry a child at such a young age. Later in life, the situation eased, but child mortality was very high in pre-medical times. A woman could give birth to 10-15 children, but not all of them would survive to adulthood. Which meant that Russian women gave birth very often.

The first person to call on when a woman went into labor was the birth assistant. Even in traditional Russia, before medical help appeared, in every village there was more than one woman who knew how to assist during childbirth. They were called povitukhas (midwives).

A peasant girl at a cradle

Sergey Lobovikov/МАММ/MDF/russiainphoto.ruPovitukhas were usually mature women with kids who were no longer able to bear children. And of course, knew how to deliver babies. This craft was hereditary in Russian villages – most povitukhas learned from their mothers. Povitukhas, the ones who helped children enter this world, were considered something like “good” witches. They knew a lot of ancient pagan magic like spells and herbs and used them in their ‘practice.’

Povitukhas believed their ‘patron saint’ was Salome, a woman who was present during the birth of Christ – however, the Gospel doesn’t mention this, so Salome was a ‘folk saint’ in Russia. At the beginning of labor, the povitukhas usually read the spell: "Mother Solomonia, take the Golden keys, open the bone birth to the servant of God" and sprinkled the woman in labor with water from a stream or river.

"Parental Joy," year unknown, by Kirill Lemokh (1841-1910)

Kirill LemokhRussian women didn’t give birth inside their homes. The izba was considered a spiritually clean place, and childbirth is a messy process that usually took place in a barn (if the season was warm enough) or a bath-house. Traditionally, Russian women gave birth standing up, holding the ends of a bed sheet draped over a ceiling beam. Olga Semenova wrote that “sometimes a woman has to hang on a beam for so long that her hands hurt for two weeks after giving birth.”

READ MORE: The wonders of the Russian izba

Povitukhas used some obsolete methods to help give birth – however, contemporary midwifery says these methods are rational. If the labor was going slow, a povitukha asked the woman to get up and go around the table three times, or to stand with legs apart wide enough for the woman’s husband to be able to crawl under the woman three times. Apparently, these methods helped induce a faster birth.

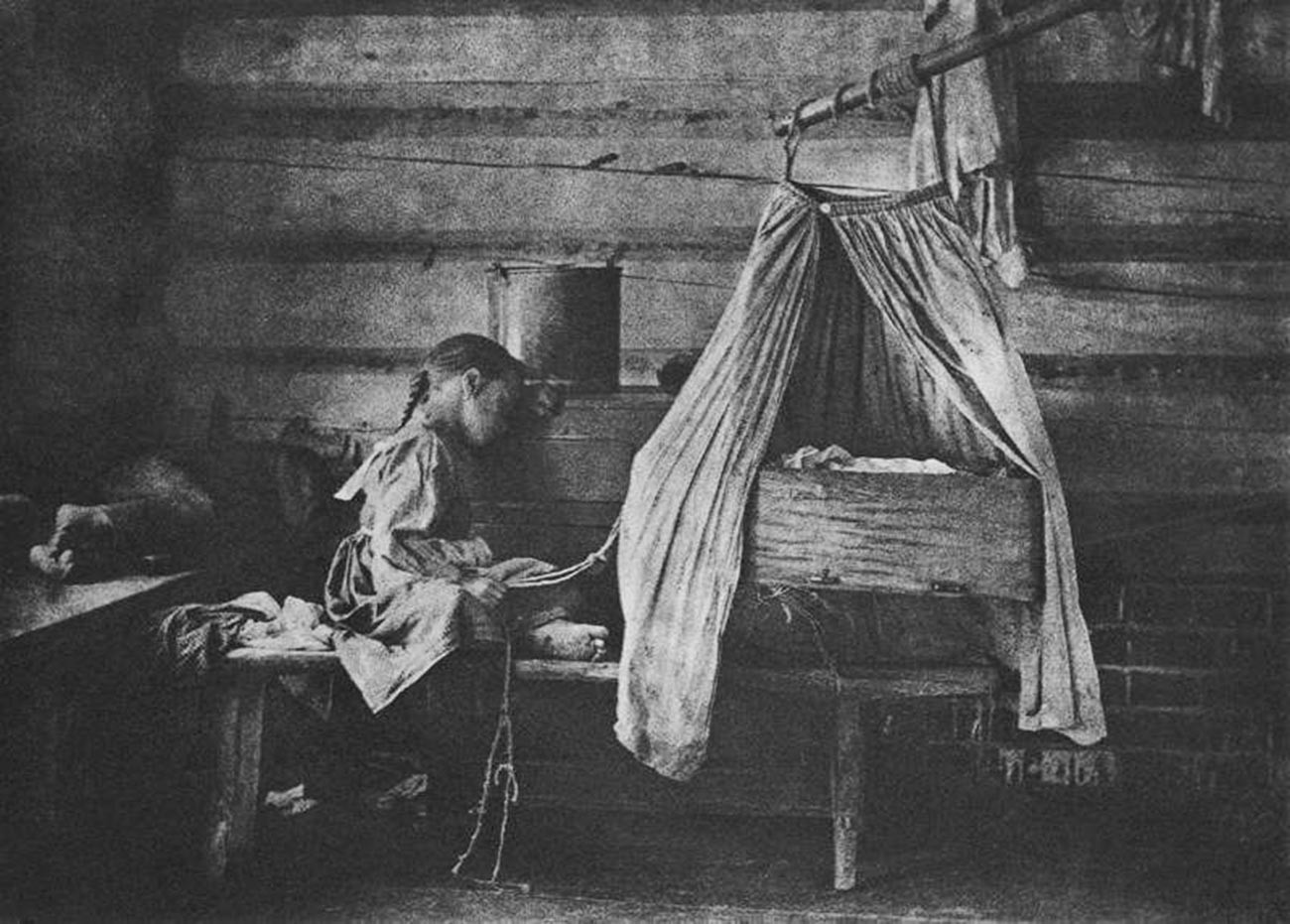

A Russian peasant woman rocking the cradle

Murom History and Art Museum/russiainphoto.ruIf labor lasted more than 24 hours, it was considered alarming (and contemporary professional midwifery is totally in agreement with this). A prayer service was ordered in the village church and the povitukha would start to use more severe methods to help the baby come out – massaging the bosom, bathing the woman in hot water etc.

Along with the church service, povitukhas could use some folk magic, ordering the relatives of the woman to open all the locks and all the doors in the house, open everything that was closed, untie all the laces on shoes, straps, belts, braids – and everybody complied. It was a strict tradition to fully obey a povitukha’s orders during the process of childbirth.

"The Baptism," 1896, by Pyotr Korovin (1857-1919)

Pyotr KorovinWhen a baby was born, it was the povitukha who cut the umbilical cord and bathed the baby for the first time. Povitukhas stayed in the mother's home for days after birth, assisting the mother and the baby. A povitukha was able to "straighten" the baby – to form an "appropriate" body and head by using simple movements. Povitukhas also healed the uterine prolapse that often occurs after childbirth.

After a period of several days, the povitukha was sent away – usually this happened after the baby’s baptism. The povitukha was paid a feel – in the form of presents. Two loaves of bread, a handkerchief, and 50 kopeks (a small sum that could buy a kerosene lamp, or a tin bucket) were the usual pay for the povitukha’s job.

READ MORE: The difference between baptism in the Russian Orthodox Church and Catholic Church

"Var'ka," 1893, by Kirill Lemokh (1841-1910)

Kirill LemokhIt was believed that once delivered, the povitukha became related to the baby for life. In Russian villages, the day after Christmas was the povitukha’s celebration day – everybody went to the homes of ‘their’ povitukhas with simple presents – they brought pancakes, pies, towels, pieces of cloth.

Only in 1757, with the help of Pavlos Condoidis (1710-1760), a Russian doctor of Greek origin, were the first professional midwifery schools opened first in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and then in many other Russian cities and towns. By the end of the 19th century, midwife was an official position in Russian towns – and professional midwives were formally subordinate to the local police administration.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox