Imposing arches with marble columns, carved ceilings with stucco, stained glass windows and elegant leather chairs — welcome to the interior of one of the first Soviet bars inside St. Petersburg’s ‘Grand Hotel Europe’.

“The hotel had a small seating area and a mezzanine with a grand piano. It was a place for leisure and relaxation. We took the carved sideboard from the former hunting office of Nicholas II: the lower section was used as a bar counter, and the upper was for drinks,” recalls Alexander Kudryavtsev, one of the first bartenders in the USSR.

Bar in the capital's Intourist hotel. 1974

Yu.Levyant/SputnikSimilar bars at expensive hotels, such as the ‘Moskva’, the ‘Berlin’ and the ‘Metropol’, opened their doors in 1965 to cater for foreigners who wanted to see the “land of victorious socialism”.

“On the first day, a Swedish man entered — my first guest — and ordered a vodka-tini. In those days, in Europe, it was customary to shorten the names of cocktails. So instead of ‘vodka with martini’ they said ‘vodka-tini’,” explains Kudryavtsev. “I knew about martini, of course. The Swede saw I was a bit confused and is like: ‘You know, I used to love dry martini, but now I switched to vodka’.” And I immediately realized that he wanted me to mix vodka and martini. It earned me my first tip — my first dollar, which I hung on the wall.”

Summer restaurant "Roof" in the Grand hotel "Europe", 1985

Dmitriev/SputnikBars came to be called ‘valyutnie’ (“currencies”), because customers would pay in hard currency (ie. foreign currency, usually U.S. Dollars). According to Kudryavtsev, visitors from abroad were often observed in bars by KGB officers, who ordinary bartenders had to “cooperate” with.

“A foreigner would be sitting near me — and if I saw that he was about to leave, I had to wink at an officer in civilian clothes, who’d be standing by the entrance to the bar,” Kudryavtsev says, sharing his experience.

Ingredients for alcoholic cocktails of the restaurant "Metropol": Stolichnaya vodka produced by the Moscow factory "Kristall", mineral water "Narzan", canned pineapple, lemon and tomato juice. 1983

M. Anfinger/SputnikOrdinary people were not allowed to visit such places and even diplomats were advised to stay away — the entrances were strictly guarded by police. However, Soviet prostitutes would somehow make it inside and, according to Kudryavtsev, foreigners often left with them. After their “work”, the girls were detained by police and questioned about their clients.

Often, hotel employees secretly bought imported things from foreigners, but only outside the bar. Thefts also happened in “currency” bars, as an employee of Intourist (one of the first Soviet travel firms founded in 1929) told Kommersant newspaper.

Bar of the Intourist hotel in Rostov-on-don. 1973

V. Kozlov/Sputnik“There was an incident with tourists, students from a military intelligence school in Germany, who came to study Russian. They were forever having their wallets and ID cards stolen or confiscated, <...> the first theft happened in a ‘currency’ bar in Kiev,” recalls an employee who wished to remain anonymous.

But the money was always returned to the tourists, in order to prove how efficient the Soviet police were, he adds.

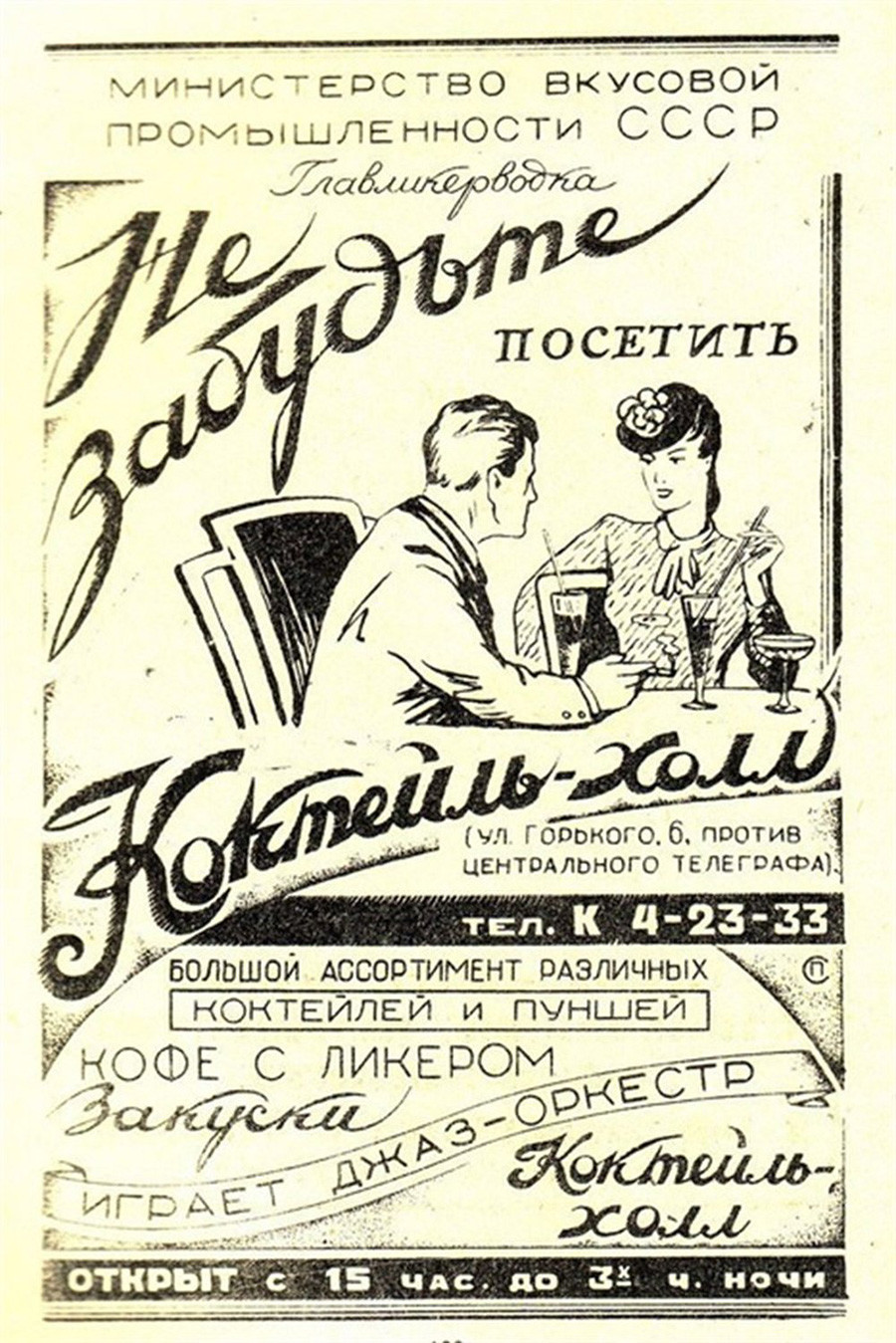

The main institution for the Soviet intelligentsia was probably ‘Cocktail Hall’, which opened back in the 1940s. The interior was sophistication itself, with a spiral staircase, columns and luxury chandeliers. The bar employed only women, who prepared punch, coffee with liqueur, cocktails and alcoholic drinks with fruits.

“You’d be sat in front of the counter at a high revolving table, sipping cherry punch through a straw — a mix of fruit water and light sweet wine, but much tastier than either. Your head might be spinning a little, but not intoxicated,” recalls Aleksandr Puzikov, editor-in-chief of the publishing house ‘Khudozhestvennaya Literatura’.

Cocktail Hall

Archive photoAmong the clientele were diplomats, writers, trendy types, officers on leave and even frontline soldiers, but everyone had to wear a tie; it was the obligatory dress code. To get inside, many donned garish ties and some even wrapped socks with elastic bands round their necks, writes Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Cocktail Hall was rumored to have been set up specially to keep an eye on spies and anti-Soviets.

The Restaurant "Prague". In the hall of Russian cuisine

S. Zhabin/Sputnik“In Stalin’s time, Cocktail Hall existed to track down anyone who was interested in the West and then eliminate them somewhere else. When the place started being raided, already after Stalin’s death, the principle was violated and everyone immediately stopped going,” says jazz artist Alexey Kozlov.

Hall of the restaurant "Aragvi". 1978

Galina Kmit/Sputnik“The ‘Praga’ restaurant in central Moscow was a real luxury, because it served genuine Czech beer, while those with stronger tastes could order vodka, cognac, champagne, port or just ordinary wine,” writes Evening Moscow, citing Moscow expert Ilya Kuznetsov.

Moscow, USSR. July 1, 1987. The Lira cafe located on Pushkin Square

Valentin Sobolev/TASSAlso popular was the 1930s restaurant ‘Aragvi’, famous for its Georgian wines and nasty rumors about a secret room, where Moscow beauties were brought to indulge high-ranking members of the Communist Party and then allegedly disappearing without a trace.

Cafe "Shokoladnitsa" on Oktyabrskaya square (now-Kaluzhskaya square) in Moscow. 1968

Vyacheslav Runov/SputnikPeople would also go to dance in the ‘Lira’ bar on Pushkin Square, which offered live music and several varieties of punch. And after that, they went to the ‘Shokoladnitsa’ cafe in Gorky Park, where women especially liked to knock back ‘Apricot’ liqueur and ‘72’ port.

Ordinary Soviets could enjoy a drink in a wine joint, many of which opened in St. Petersburg after the Great Patriotic War.

“There was a notorious place on the corner of Mayakovskaya and Nekrasov streets, full of invalids without legs. It wreaked of musty sheepskin and misfortune. It seemed that former officers and soldiers on crutches went there just to get smashed and have a fight,” recalls writer Valery Popov.

Beer "Ladya"

personal archiveAs the 1970s drew nearer, more beer bars began to open where anyone could drink, one of the main ones being ‘Yama’ (the common Soviet name for the ‘Ladya’ ale house in Moscow). There, in the words of fashion designer Egor Zaitsev, criminals, poets, musicians and simple students went to hang out. There were no chairs, everyone stood, yet that didn’t stop people lining up to get inside.

“It had a really carefree atmosphere. People drank beer, ate shrimps, talked about all sorts of things, especially music. There was a kind of romance to it all: people with tattoos, former athletes, inebriated artists. No bad stuff, nothing but folk wisdom and troubled lives expressed in tattoos remained in the memory,” recalls Zaitsev.

Men with beer mugs 1961-1969

Vsevolod Tarasevich/MUMM/MDFThe ‘Zhiguli’ beer bar was another popular haunt, where copious amounts of Soviet Zhigulevskoe beer was poured and served with boiled crayfish. It was the gold standard among Soviet — and later Russian — beer bars. In 2012, even Russian President Vladimir Putin was seen relaxing there.

“On top of that, there were ordinary beer stalls scattered throughout the USSR. As with many products, people lined up for beer and those who pushed in got called ‘mujaheddin’,” says Mark Gottlib, deputy editor-in-chief of newspaper ‘Novaya Sibir’.

“At every beer stand, you would see several individuals squatting and sipping beer from three-liter cans, types with faces normal people usually try not to look at. But to save time and nerves, it was easier to go up to them and utter the sacred phrase: ‘Guys, I’d like a beer.’ The cost of facilitating the purchase was one ruble [enough for 10 movie tickets or 5 loaves of bread — Ed.]. Like icebreakers, these guys cut a path to the kiosk window and, a few minutes later, your canister was full. Often the line refused to let them through, sometimes it ended in fisticuffs,” Gottlib recalls.

Beer hall date of Semka,1975

Valery UsmanovThe coveted beverage was poured into three-liter glass jars or even ten-liter cans, while some drank beer from ordinary plastic bags, having punctured a small hole in them.

Lastly, some bars had beer vending machines, popularly known as ‘autopoilki’ (“auto drinking bowls”). The principle was simple: “You bought a token, put it in the machine, turned the lever and waited until your mug was filled to the top with beer. However, some knew how to extract the amber nectar for free,” says Evgeny Pyatunin, a local historian from the city of Kirov (955 km from Moscow).

Beer vending machine

Archive photo“A hole was drilled in the token and a fishing line attached, everything was soaped. You could then slide the token in and out, and the beer flowed like a river — that is until the ‘barman’ came running out, disbanded the freeloaders and confiscated the makeshift contraption,” writes Pyatunin in his book Treatise on Beer.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox