Italian officers on the Eastern front.

Paxox(CC BY-SA 4.0)"When an Italian soldier knows what he is fighting for, he doesn't fight badly, as was the case in the time of Garibaldi. In this war, however, soldiers not only do not know what they are fighting for, but they did not want this war and do not want it. Therefore, they only think of returning home," a bersagliere (elite rifleman) of the Principe Amedeo Duca d'Aosta Division, dispatched by Italian leader Benito Mussolini to the Eastern Front in the summer of 1941, said about Italy's involvement in the military campaign against the USSR.

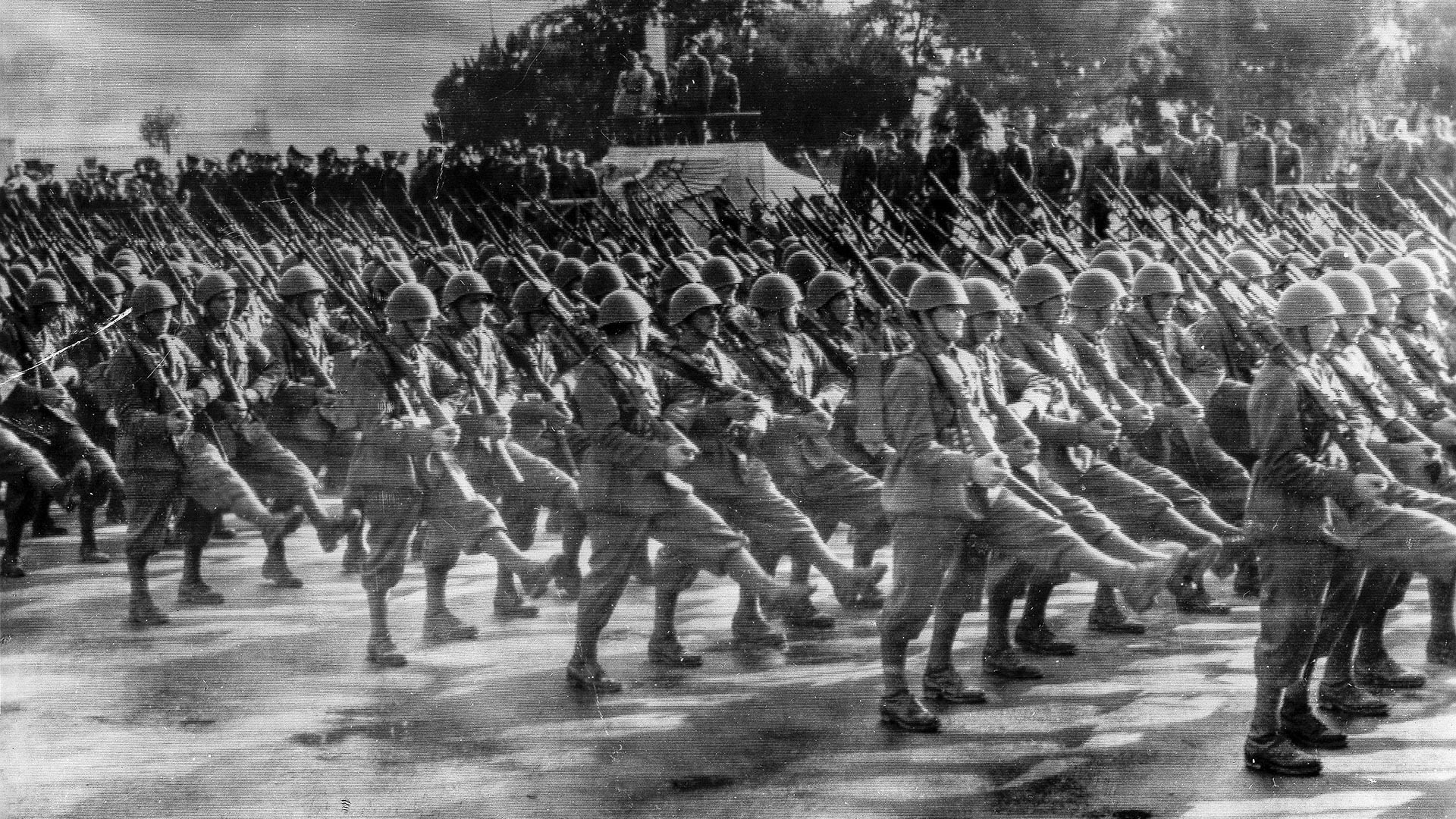

Parade of Italian troops in Rome.

Getty ImagesDespite Italy's declaring war on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 — the day Operation Barbarossa was launched [the German invasion of the Soviet Union] — there were no Italian soldiers in the invading army then. Initially, Adolf Hitler didn’t intend to involve his main ally in the "Crusade against Bolshevism" because he felt that Rome had enough on its plate already. It had substantial occupation forces in Albania, Greece and Yugoslavia, and the Italian possessions in East Africa had been all but lost. In North Africa, the Italians managed to stand their ground only thanks to support of the German forces led by General Erwin Rommel that had been sent there. Despite this, Benito Mussolini persuaded the leader of the Third Reich to give his troops a chance to show what they could do in the war against the Russians.

Benito Mussolini visits Italian troops on the Eastern front.

Legion MediaThe first Italian soldiers arrived on the Eastern Front in August 1941. The so-called Italian Expeditionary Corps in Russia (Corpo di Spedizione Italiano in Russia, or CSIR) numbered over 62,000 men, including 600 Italian "SS-men" — Blackshirts of the Voluntary Militia for National Security (Milizia Volontaria Per La Sicurezza Nationale) who were deeply loyal to the regime. Air support was provided by 51 Macchi C.200 Saetta fighter aircraft of the Italian Royal Air Force.

Bersagliere in Stalino (Donetsk).

Public DomainThe first weeks of the CSIR's operations in the Soviet Union demonstrated that Italy was completely unprepared for the war. The supply of provisions, combat clothing and ammunition was abysmally organized. The situation regarding road transport was even worse — Italian trucks couldn't last long on Russian roads. Soldiers of the Torino Division, forced to march over 1,300 km from the Romanian border eastwards, compared themselves to lowly foot-soldiers of the Middle Ages taken to war by their German masters who travelled comfortably on horseback.

Bersagliere in the USSR in 1942.

Public DomainThe armaments of the corps were a particular problem — their 47 mm anti-tank guns proved helpless against Soviet T-34 tanks. Their rounds only slightly dented — or just ricocheted off — the armor of enemy tanks. As far as the armored force was concerned, the Italians only had L3/33 and L3/35 tankettes, incapable of fighting Red Army tanks on equal terms. When the frosts hit, the fighter aircraft began to let the Italians down: The Macchi C.200s had been built with the Mediterranean theater in mind, not the Russian winter.

Benito Mussolini inspects the four guns he sent with the first division of soldiers to the Russian front.

Getty ImagesAll the above factors led to the commanders of Army Group South being constantly unhappy with the Italian corps under the group's command. Despite some successful local operations by the Italians (such as the "Christmas Battle" on the River Mius on Dec. 26, 1941), the Germans had a low opinion of the Italians as soldiers. "The Italian divisions are unfortunately so ineffectual that they can be employed for nothing more than passive flank cover in the rear of our positions," Franz Halder, chief of the Army General Staff, wrote in his war diary.

'Sforzesca' division in action.

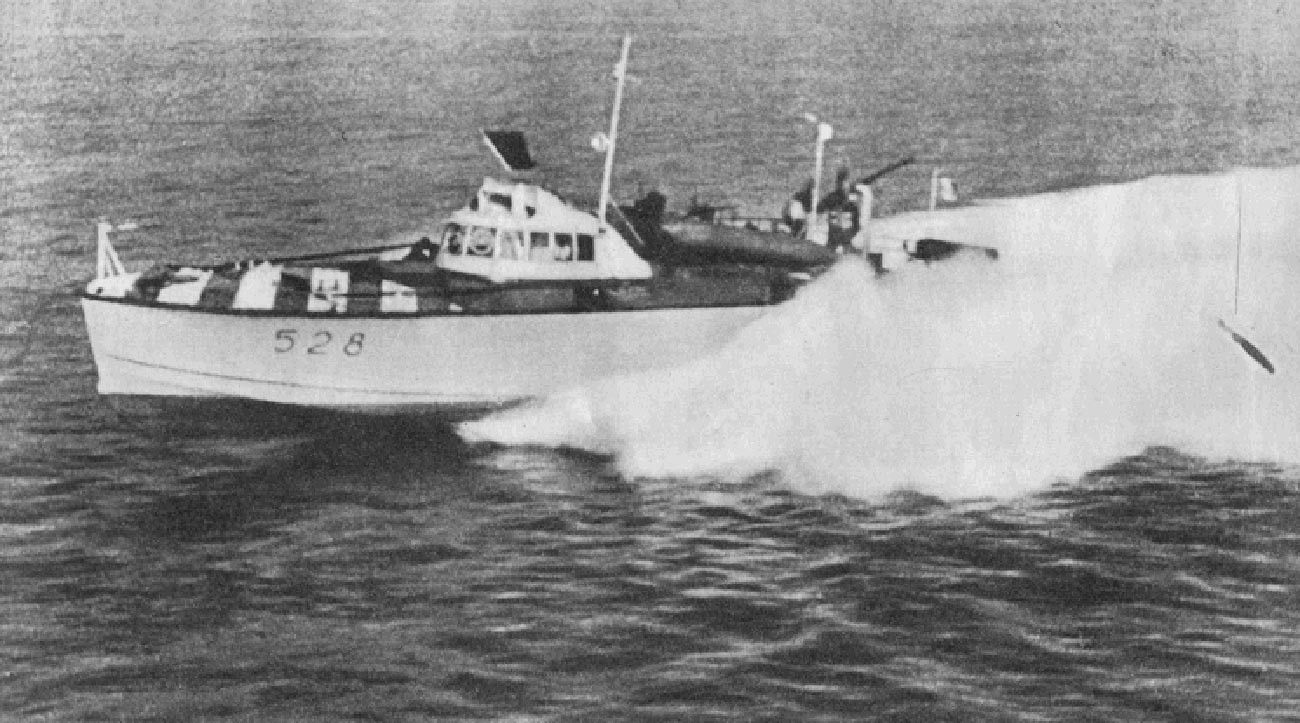

Public DomainThings were different with the Italian Royal Navy, which earned high praise from the Germans. One of the most effective special submarine units of World War II, the 10th Assault Craft Flotilla, was on active service in the Black Sea, where its torpedo-armed motorboats, midget submarines and sabotage parties successfully fought Soviet troops and naval forces in the Crimea. Several boats were even deployed to the Baltic, despite the distance from Italy.

MAS 528 torpedo boat on Ladoga lake.

Public DomainAs far as their interaction with the local population and Red Army prisoners of war, the Italians were much more humane than the Germans, Hungarians or Romanians. "Early on the morning of Oct. 21, 1941, Italian troops were already in the town," recalled Yekaterina Mateychuk (Gayduk), a resident of the Ukrainian town of Krasnoarmeysk. "And we, children, ran to see what fine uniforms they had: Berets with brightly-colored feathers, aiguillettes… There was nothing frightening about them, but the Italians departed very quickly and it was only when the Germans arrived in the town and began their atrocities that we could of course see the difference… Despite the fact that the Italians attempted to distance themselves from the brutal methods of their allies, the CSIR's path through Soviet territory was also marked by a number of war crimes: Murders of civilians, rapes, looting and destruction of infrastructure.

Italian soldier in Kharkiv.

BundesarchivBy the summer of 1942, the Expeditionary Corps had lost around 15,000 men — a quarter of its strength. Mussolini decided significantly to reinforce his military grouping in the USSR and in July the 8th Army, also known as the Italian Army in Russia (Armata Italiana in Russia, or ARMIR), was deployed on the basis of the Corps. It numbered 235,000 men, but the earlier problems with supplies and weapons had not gone away. A small group of 19 light L6/40 tanks at its disposal was incapable of becoming a strike force of any significance, so German armored formations were periodically brought in to reinforce ARMIR.

L6/40 tank.

Public DomainThe Italian troops' most prized asset on the Eastern Front were the several divisions of elite mountain infantry forming the so-called Alpine Corps. Accustomed to the cold and well armed, equipped and trained, they were regarded as the most reliable units in the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy. They repeatedly had to bail out ARMIR when it faced serious Soviet resistance.

Italian troops in the Soviet Union.

Getty ImagesThese hard times soon came for the Italians. After the Wermacht's 6th Army was encircled at Stalingrad in November 1942, Soviet troops struck at the Italian 8th Army on the Don. In the course of several offensive operations in December and January, the Italians were completely smashed. Sergei Otroshchenkov, a tank crewman of the 18th Tank Corps, recalled a successful surprise attack on withdrawing ARMIR units near the village of Petrovsky: "When the Italian forward units drew level with us, the order was sent along the (tank) columns: ‘Advance! Crush!’ We gave it to them from both flanks! I've never seen such carnage since. We literally smashed the Italian army into the ground… It was winter and our tanks were whitewashed for winter camouflage. And when we withdrew from battle, our tanks were red below the turrets. It was as if we had been swimming in blood. I examined my tank — in one place there was a hand stuck to the tracks, in another a fragment of a skull.”

The retreat of ARMIR.

Public DomainThe retreat of the defeated ARMIR from the Don westwards recalled the flight of Napoleon's Grande Armée from Russia in 1812. "Exhausted men fell in the snow never to get up again," recalled Eugenio Corti, an officer of the Pasubio Division. "Some were going mad and did not understand they were dying. The most tenacious of the men continued to drag themselves along the road for a long time, until the strength of these unfortunates finally ran out. The most frequent stories I heard were of mental confusion. I remember being taken aback by the story of someone who all of a sudden had burst out laughing, sat down in a snow drift, taken his boots off and set about burying his bare feet in the snow. After he had finished laughing, he loudly sang something very jolly. There were a great many similar cases.” Only the Alpine infantry covering their comrades' withdrawal periodically put up any organized resistance.

Dead Italian soldiers.

Getty ImagesDuring the fighting in Russia, the Italian 8th Army lost more than 114,000 men killed, captured or missing. Having achieved nothing, the bloodied and depleted troops were withdrawn home in the spring of 1943. The disaster of the Italian Army in Russia shocked Italian society and was one of the main reasons for the rapid fall of Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime soon afterwards.

Soviet troops with the captured standard of an Italian regiment.

Getty ImagesIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox