The only description of Sophia’s physical appearance was left by her contemporary, a French diplomat Foy de la Neuville. According to him, “she is terribly fat, has a head the size of a pot, facial hair, lupus on her legs and is at least 40 years old.” In fact, in 1689, when de la Neuville saw her, she was just 32. However, “her intelligence and virtues do not bear the imprint of the ugliness of her body, for as much as her waist is short, wide and rough, so her mind is thin, shrewd and skillful,” de la Neuville wrote.

Indeed, Tsarevna (Princess) Sophia (1657-1704), daughter of Tsar Alexis (1629-1676) left a meaningful legacy in Russian history. In the 17th century, when women, even the nobler ones, were totally banned from political and social life, she was at the head of the state for seven years. Much later, Catherine the Great of Russia would write: “To do Sophia justice, she ruled the state with as much prudence and intelligence as could be desired from the time and the country where she reigned in the names of her two brothers...”

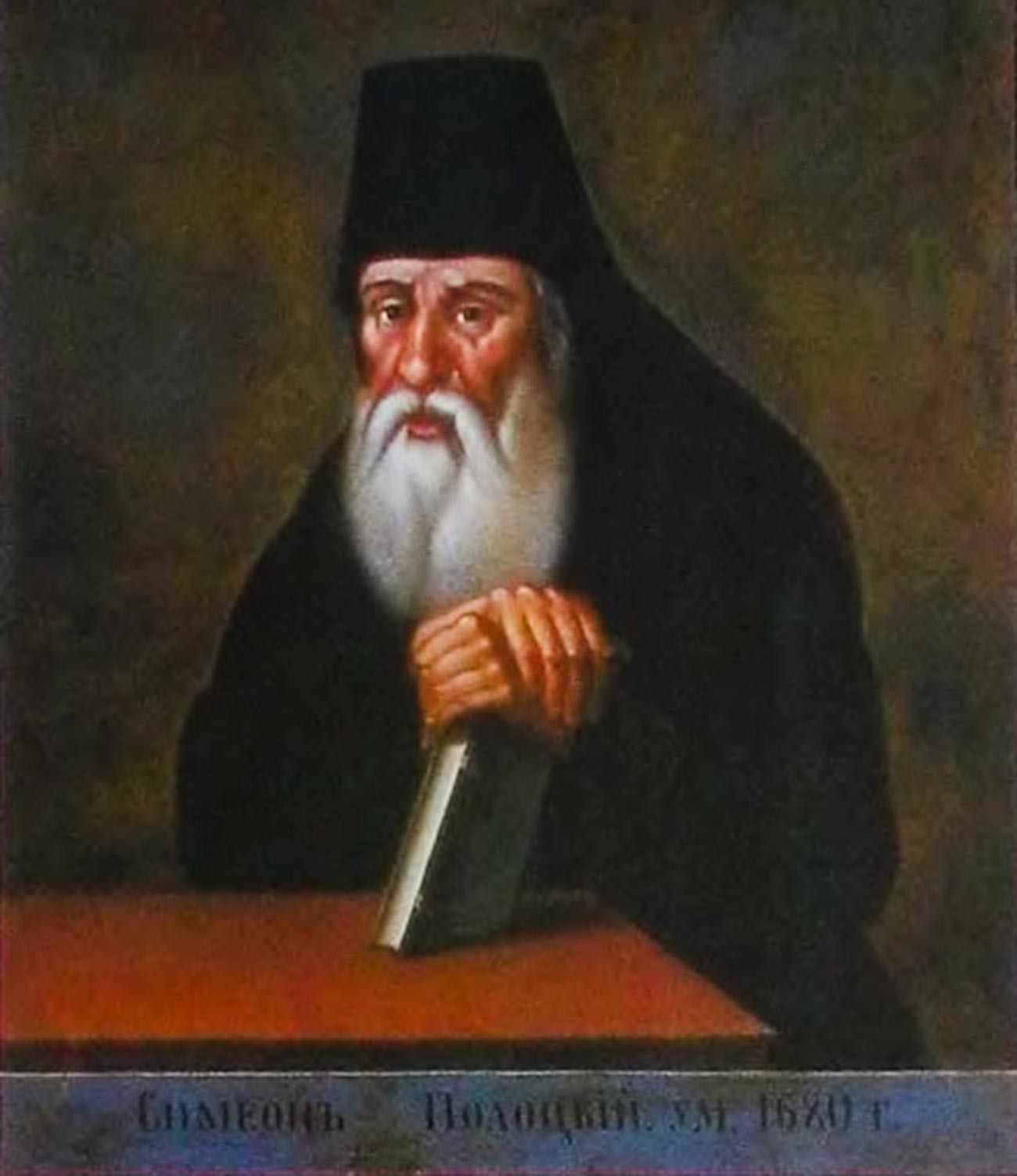

Simeon Polotsky (1629-1680)

Public domainEducation wasn’t necessary in the 17th century, even for a tsar’s daughter. However, Sophia demonstrated interest in literacy from an early age. That’s why, as well as her brother Alexey Alexeevitch (1654-1670), she was taught by Simeon Polotsky, a Polish scholar and poet. Befitting for any educated person of her era, Sophia knew Latin and Polish and had a big library – mostly of religious books. Some of these books are still preserved in the Novodevichy Convent in Moscow!

Brought up in the family of the pious Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich, Sophia spent her life “in front of the church altar and icons, and the circle of her reading consisted of the Psalter, the Gospel and hagiographic literature,” Lindsey Hughes, a British historian, writes.

Anyway, in the Russian political system, there was no place for a tsar’s daughter anywhere near the reins of state power. So Sophia couldn’t even think of getting to the throne until a dynastic crisis created favorable conditions for this.

In 1676, Tsar Alexey died. He was succeeded by his son Feodor Alexeevich (1661-1682), who had very weak health. When Feodor died at just 21, a clash of the ruling clans followed.

Ivan (1666-1696), Alexey’s son from his first marriage to Maria Miloslavskaya, was the next in succession to the throne. However, the Naryshkins, relatives of Alexey’s second wife, Tsarina Natalya Naryshkina (mother of Peter I) worked their politics to make Peter, the younger brother, the next Tsar (read more about this unique part of Russian history here).

"Tsarina Natalya shows Ivan to the streltsy," by Nikolay Dmitriev-Orenburgsky

N. D. Dmitriev-OrenburgskySoon, the Miloslavskys, led by Sophia, had their revenge. “Sophia couldn’t stand the idea of her mother-in-law, whom she hated, [indirectly] becoming the ruler,” Russian historian Sergei Soloviev explains. So in May 1682, the Miloslavskys ignited an uprising of streltsy, the royal guard, by telling them Ivan was killed by the Naryshkins. Bloodshed followed: Ivan and Afanasiy, tsarina’s brothers, their advisor Artamon Matveev and many other Boyars (noblemen) loyal to the Naryshkins were all murdered and Ivan eventually became tsar along with Peter, with Sophia becoming the Regent of Russia.

Double throne for Peter and Ivan

Moscow Kremlin MuseumsPeter and his mother Natalya Naryshkina left the Kremlin to live in a palace in Preobrazhenskoe near Moscow, where Peter started his first military exercises. Meanwhile, Sophia lived in the Kremlin with her foremost aide and counselor, Prince Vasiliy Golitsyn (1643-1714), a seasoned military commander and court official, who was 39 at the moment of Sophia becoming the regent. So, alongside a formal tandem of the Tsars Ivan and Peter, there was also an actual ruling tandem of Sophia and Prince Golitsyn.

There are numerous rumors and stories of Sophia’s intimate relationship with Vasiliy Golitsyn, which, if true, again marks her unusual behaviour for the era – an extramarital affair for a tsar’s daughter was seemingly unthinkable at the time (moreover, Golitsyn was married and had children). There are probably no sources that would undeniably prove Sophia and Vasiliy were lovers. But we have Sophia’s letter to Golitsyn, that, among other things, says: “I can’t believe, oh light of my eyes, that you are coming back, but I’ll believe it then when I see you, oh light of my eyes, in my arms.”

Tsars Ivan and Peter and the ruler Sofia, 1682-1689

Vasiliy VereschaginIt’s hard to determine whether Sophia personally took real action in government matters. Until 1686, her name didn’t even appear alongside Tsars Ivan and Peter in official documents. Still, under Golitsyn, who was the head of Moscow Tsardom’s foreign affairs since 1682, Russia led a successful foreign policy.

Under the conditions of the Treaty of Perpetual Peace (1686), that ended the war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that lasted from 1654, Russia regained control over the lands of the Left-bank Ukraine, Kiev, Smolensk etc. Also, the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) was immensely important – it began diplomatic relations with China and opened official trade between countries.

"Tsarevna Sophia in 1698," by Ilya Repin

Ilya RepinSophia, apparently, led a lush life behind the throne. In 1688, she ordered from Hamburg “two hats with ostrich feathers, two round mirrors in a tortoiseshell frame, tortoiseshell boxes, fans, ribbons...” It was during this period when her portrait inside a two-headed eagle, Sophia holding sceptre and orb, was created.

Befitting her pious image, Sophia was firmly against the Old Believers and, in 1685, issued the ‘12 Articles’ – a law that put death penalties (including burning alive) on Old Believers who wouldn’t denounce their faith. However, the law stimulated more self-immolations among the Old Believers. Russian historian Lev Gumilev called ‘12 Articles’ “one of the most ruthless laws in the Russian penal practice”.

However, Sophia herself had to return to religious practices, as eventually, she was confined to a monastery – a popular practice of removing royal women from social and political life in the 17th century. By the time Peter had turned 17 in 1689, he was already married to Evdokiya Lopukhina and, thus, fully capable of ruling. Ivan V was married, too. There was no more need in Sophia as a regent – but she didn’t want to give up the reins of the state, with streltsy supporting and protecting her in the Kremlin.

Novodevichy Convent in Moscow

W. Bulach (CC BY-SA 4.0)The situation cracked when Peter issued a death penalty for those streltsy who wouldn’t obey his orders. As Peter was the rightful heir to the throne, Sophia lost the royal guards’ support. Her sidekick Vasiliy Golitsyn removed himself from political life, having left for his sub-Moscow estate, and eventually, Peter ordered Sophia to live in Novodevichy Convent in Moscow.

But Sophia didn’t yet live there as a nun – she stayed in several cells with her suite, under supervision of the guards. In 1698, after another streltsy uprising that she seemed to have supported, she was ordered to take a monastic veil under the name Susanna. She died 6 years later, in 1704, and is interred in the Smolensk Cathedral of the Novodevichy Convent.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox