Today, few people in Russia remember the name of this man. Whereas in Stalin’s time, the head of Soviet propaganda, Alexander Sergeyevich Shcherbakov, was one of the most influential people in the USSR. Furthermore, he had every chance of some day becoming the head of state. But it was not to be.

After the victory in the Russian Civil War, the Soviet leadership faced an acute personnel problem. There were many brilliant military commanders, but a dire shortage of civilian specialists. In those circumstances, Alexander Sergeyevich, a born leader and a good organizer, who had several university degrees, was worth his weight in gold.

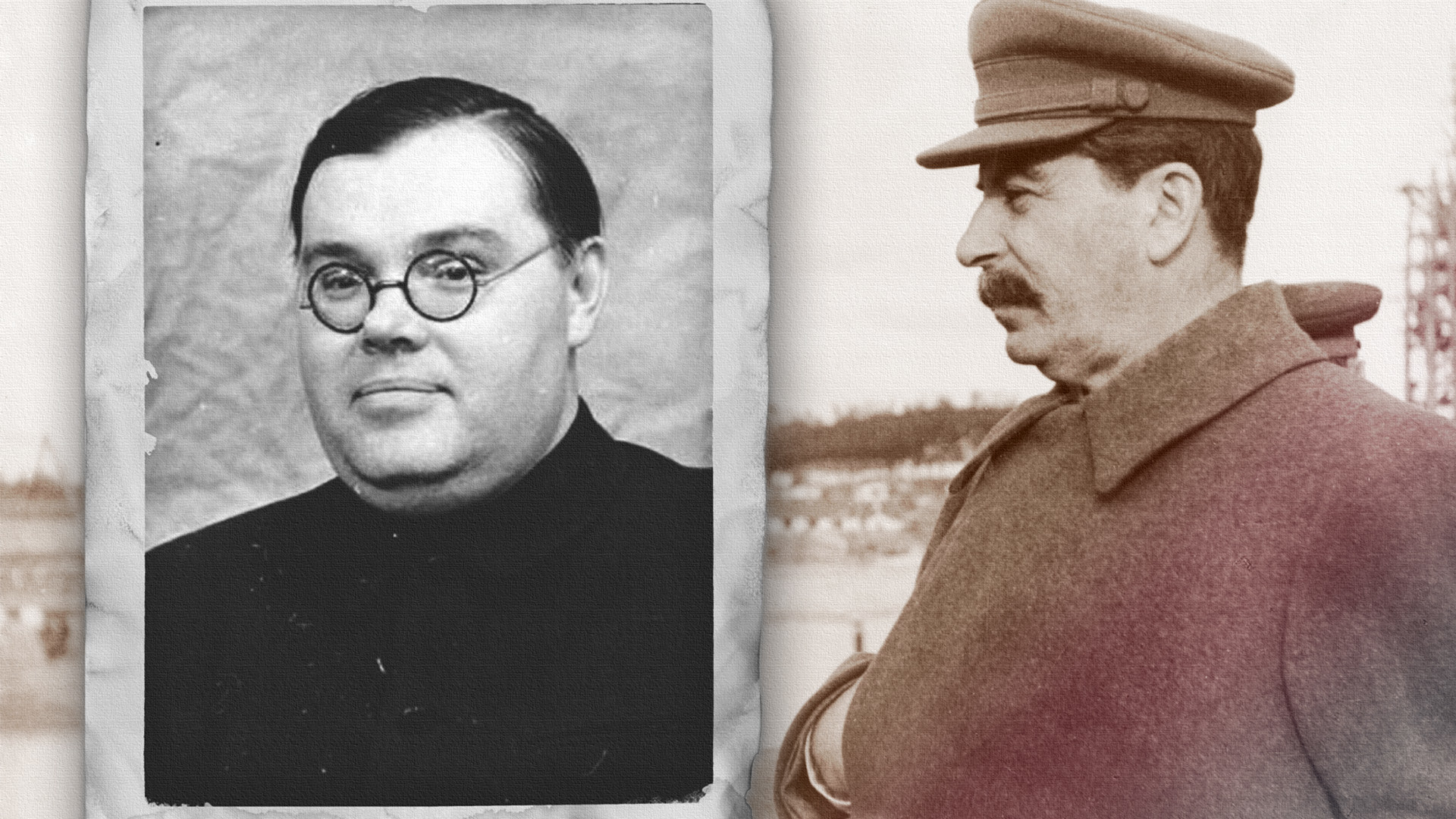

Alexander Shcherbakov (R).

Archive photoAlready at the age of 15, Shcherbakov set up and headed several youth revolutionary organizations and at the age of 33, he rose to the post of the executive secretary of the USSR Writers’ Union. It was he who ensured the publication of literary works depicting “the heroic struggle of the international proletariat, the pathos of the victory of socialism, reflecting the great wisdom and heroism of the Communist Party”. It often depended on Alexander Sergeyevich whose works would be published and whose would not.

Alexander Shcherbakov.

Archive photoEven after Shcherbakov left his post in the Writers’ Union in 1936, he continued to closely follow developments in Soviet literature. “In terms of his cultural level,” famous poet Korney Chukovsky wrote in his diary in 1962, “he was a senior janitor. When I wrote We Will Defeat Barmaley and artist Vasilyev denounced me, alleging that I had said that he should not be drawing Stalin next to Lenin, I was summoned to the Kremlin and Shcherbakov, stamping his feet, scolded me, shouting obscenities. It shocked me. I had no idea that under any political system any illiterate bastard had the right to shout at a gray-haired writer. At that time, both my sons were at the front, while Shch-v’s son (I knew that for certain) was tucked away somewhere on the home front.”

First row: Molotov, Stalin Voroshilov. Second row: Malenkov, Beria, Shcherbakov

Archive photoAfter working in the Writers’ Union, Shcherbakov held several senior positions in different parts of the country: in Leningrad (St. Petersburg), Stalino (Donetsk), Irkutsk. Finally, in 1938, Stalin brought him to Moscow, where Alexander Sergeyevich was put in charge of the Moscow branch of the Communist Party. “The Politburo (the governing body of the Communist Party of the USSR) is now full of old people,” the leader said at a plenum of the Central Committee. “Of people departing, whereas what is needed is to recruit some younger people, who could take things on and, if necessary, be ready to replace [the old guard].” Under Stalin’s patronage, Shcherbakov became a candidate for membership in the Politburo, thus almost reaching the very heights of power.

Alexander Shcherbakov among the Soviet leaders.

Archive photoTwo days after the Nazi invasion of the USSR, a Soviet Information Bureau was established, whose job was to ensure round-the-clock coverage of the hostilities for the benefit of the country’s population. It was headed by Alexander Shcherbakov. In 1942, he was also appointed head of the Main Political Directorate of the Red Army, responsible for the correct ideological education of soldiers and sailors.

Alexander Shcherbakov during the 1941 Parade.

Archive photoThe most memorable and difficult period in Alexander Sergeyevich’s career was in October 1941, when the German army was just kilometers from Moscow. Between October 15 and 17, the city was gripped by panic, residents were fleeing en masse and there were robberies and looting. Shcherbakov did a lot to bring the situation in the city back to normal. He made sure that directors of enterprises who had fled the city were brought before a tribunal and that party leaders who had succumbed to fear were expelled from the party. On Stalin’s instructions, Alexander Sergeyevich delivered a radio address seeking to calm the residents of the city: “We shall fight for Moscow tenaciously and fiercely, to the last drop of blood.”

Through Shcherbakov’s efforts, propaganda work in the Red Army rapidly gained momentum. He saw the task of the Main Political Directorate in “better informing the service personnel about the atrocities of the German fascist invaders, about their aim to exterminate the Soviet people and turn survivors into slaves. And using it to instill a burning and merciless hatred of the enemy.”

Alexander Sergeyevich increased the number of political workers in the Armed Forces, dispatching them to the most difficult sectors of the Soviet-German front. Propaganda work among Red Army soldiers from ethnic republics, many of whom did not speak any Russian, was stepped up. There were even newspapers in their native languages published for them.

Alexander Shcherbakov and Semyon Budyonny.

Archive photoDozens of front-line theaters and hundreds of travelling concert teams were set up to perform for soldiers at the front and many war propaganda movies were made (one of them, Moscow Strikes Back, even was awarded an Oscar in 1943). Long-range aviation was also used to drop leaflets over the occupied areas. The country’s foremost writers and even the Russian Orthodox Church were involved in the propaganda effort.

Opening of new Elektrozavodskaya metro station.

Archive photoThose who worked with Shcherbakov described him thus: “Possessing a great capacity for work and an outstanding memory, he could quickly analyze the situation and make a decision. He was a good listener and knew how to, with great tact, correct a comrade, if necessary, and suggest the correct decision.”

When preparing for major military operations, Stalin often sought advice from his protégé. “I.V. Stalin trusted A.S. Shcherbakov, - Marshal Alexander Vasilevsky wrote in his memoir My Life's Work. – He signed papers agreed with or endorsed by Alexander Sergeyevich without any delay."

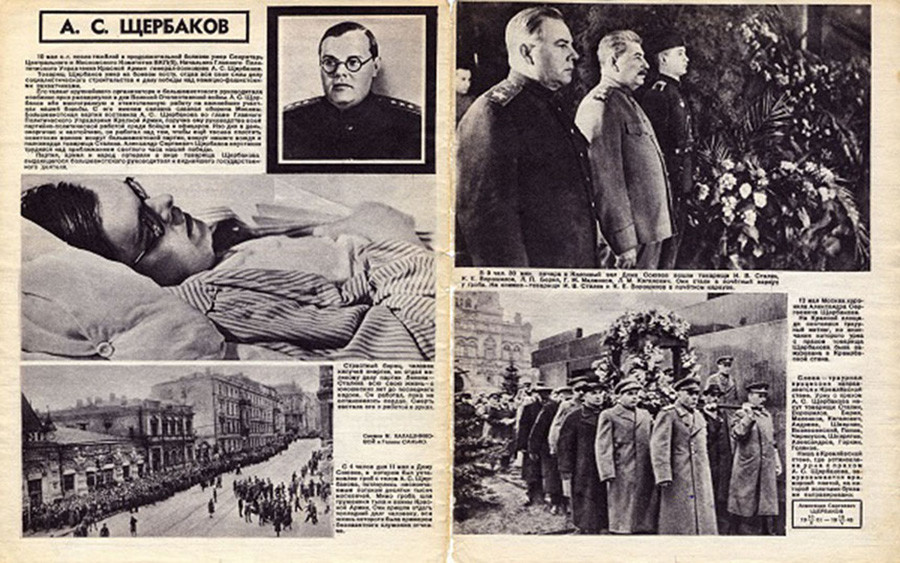

Alexander Shcherbakov obituary.

Archive photoYoung, ambitious, tough (sometimes cruel) and deeply loyal to Stalin, Alexander Shcherbakov had every chance of becoming a frontrunner for the highest post in the country after the Soviet leader’s death. However, poor health and alcohol addiction prevented him from living up to that moment. He died of a massive heart attack the day after Victory Day on May 10, 1945, at the age of just 43.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox