“Aunt Maria Vasilyevna persecuted me cruelly for my barbarous French, for trying to wear glasses, which I always had in my pocket, or to take snuff tobacco,” Russian historian Dmitry Sverbeev (1799-1874) once wrote. Indeed, wearing glasses was even considered rude at one point in Russian history.

Mikhail Feodorovich of Russia by anonymous (1772, Kremlin)

Shakko/WikipediaThe first known person in Russia to wear glasses was Tsar Mikhail Feodorovich, the first Romanov. In 1614, “crystal glasses were bought for the sovereign, with one side faceted, and with the other one smooth. And when looking through them, a lot of things are revealed,” Moscow court records state.

Glasses for correcting myopia were introduced in Europe in the 16th century and appeared in Russia about a century later. In 1636, Mikhail Feodorovich gave a pair of glasses to his confessor priest as a gift.

In 1671-1672 alone, “491 dozen” glasses (5,892 lenses) were shipped into Russia through Arkhangelsk, which means in Moscow and other big cities, glasses already had their customers. Tsar Alexey Mikhailovich had 6 pairs of glasses, Patriarch Nikon had 8. One of them is preserved in the Moscow Kremlin’s Patriarch’s Sacristy. It is kept in a silver pear-shaped case decorated with silvercast birds. The glasses are foldable.

Various glasses of the 16th-17th centuries, Europe

Wellcome Images (CC BY 4.0)Ophthalmologists were in demand in Russia: In 1669, Tsar’s officials tried to hire ophthalmologist Johann Ericsson from Sweden, but the offered pay didn’t meet the doctor’s demands.

By the second half of the 17th century, Russian craftsmen engaged in visual professions – scribes, icon painters, wood carvers, goldsmiths, silversmiths, watchmakers, as well as embroiderers – also began to use glasses.

Catherine the Great's glasses

Shakko/WikipediaPeter the Great, in his quest for the development of Russian naval fleet, needed optical glass – first of all, for naval telescopes! He founded several glass-producing factories and invited a German optician Login Sheper, who taught the first optic specialists in Russia. But Russian production of optical glass didn’t really take off until the late 19th century. Most of the glasses Russians wore were European.

Catherine the Great started to experience problems with eyesight in 1770 and a 1219-ruble looking glass in a golden rim with diamonds was ordered for her. One of her glasses (this time, a usual pair, worn on the nose) is still intact.

A lorgnette that belonged to Paul I of Russia, with his portrait engraved on the lid.

Archive photoPaul I, Catherine’s son, inherited his mother’s myopia. He, as well as his wife Maria Feodorovna, used lorgnettes (a pair of spectacles with a handle) in their everyday lives. But Maria Feodorovna was also very strict in observing the court etiquette and she thought, historian Igor Zimin writes, “that glasses destroy the image of a traditional Russian sovereign”, so she refrained from using a lorgnette or glasses in public. “Not wishing to use the lorgnette, I couldn’t see the facial expressions, but I saw that many women had handkerchiefs in their hands,” Maria Feodorovna wrote about the funeral of her son, Emperor Alexander I, in 1826. Obviously, at the time, using glasses in public was considered a faux pas, especially for the Empress Dowager (given to the wife of a deceased emperor of Russia), which Maria Feodorovna became in 1801, when Emperor Paul was murdered).

Alexander I, son of Paul and Maria Feodorovna, had congenital myopia. He, too, had to use a lorgnette and he needed it so often that he had to carry it under the cuff of his parade uniform. Alexander always lost or broke his lorgnettes and monocles (one of the preserved Alexander’s monocles is broken), so he started adjusting his lorgnette to the button of his uniform’s sleeve.

Alexander I's broken monocle

Moscow Kremlin MuseumsEven being an Emperor, Alexander was shy of his poor eyesight and the use of lorgnette. Sophie de Choiseul-Gouffier, a lady-in-waiting of Alexander’s wife Elizaveta Alekseevna, remembered: “Before taking his leave, the Emperor got up and, without saying what he was looking for, began to carefully examine the floor in all corners of the living room. I put the lamp on the carpet and also began to search for the lost object: it turned out that the Emperor was looking for a small lorgnette, which he usually used, and which fell at my feet, under the table.”

Portrait of His Highness Prince Alexander Gorchakov

Hermitage MuseumNot even to a lady-in-waiting, in fact, a palace servant, could the Emperor reveal that he needed a lorgnette! Why? It was still considered “rude” to use glasses in public, as if one needed to observe something very intensely. A legend says Count Ivan Gudovich (1741-1820), Governor General of Moscow in 1809-1812, hated people in glasses. Even in other people’s houses, when he saw somebody in glasses eyeing him, he would send his servant to this person with a message: “There’s nothing for you to look at so closely here. Take off your glasses, please.” Also, Gudovich never accepted people in glasses in his home or work office. It kind of resembles the privacy concerns surrounding the infamous Google Glass – the augmented reality headset capable of recording everything its owner looked at discreetly?

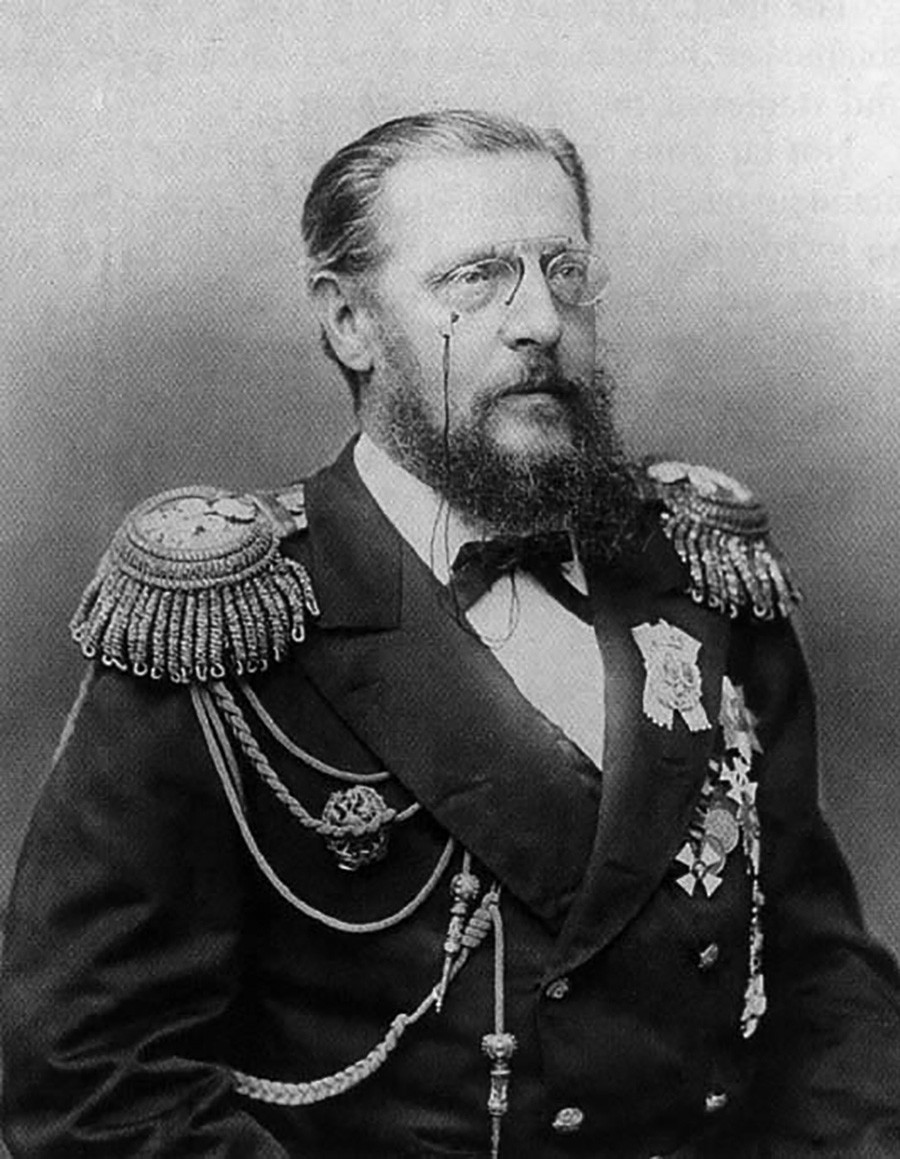

Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich

Public domainThe nonsense went further. Diplomat Alexander Gorchakov had to ask the Emperor for special permission to wear glasses while in court. In society, looking through glasses at a woman or at a senior officer was considered impertinent: glasses made it look like one was searching for visible flaws.

The artifacts of the epoch show that in the first half of the 19th century, people tried to hide their lorgnettes: there are fans and pocket watches with hidden looking glasses. On the contrary, the first Russian dandys used lorgnettes demonstratively. There was even a verb “to lorgnette”, which meant explicitly examining somebody through a lorgnette. In Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, when the protagonist goes to the theater, “his double lorgnette trains upon the lodges of strange ladies”, – thus, Pushkin underlines that Onegin is a true dandy and a womanizer. Since the 1840s, monocles were also in wide use in Russia.

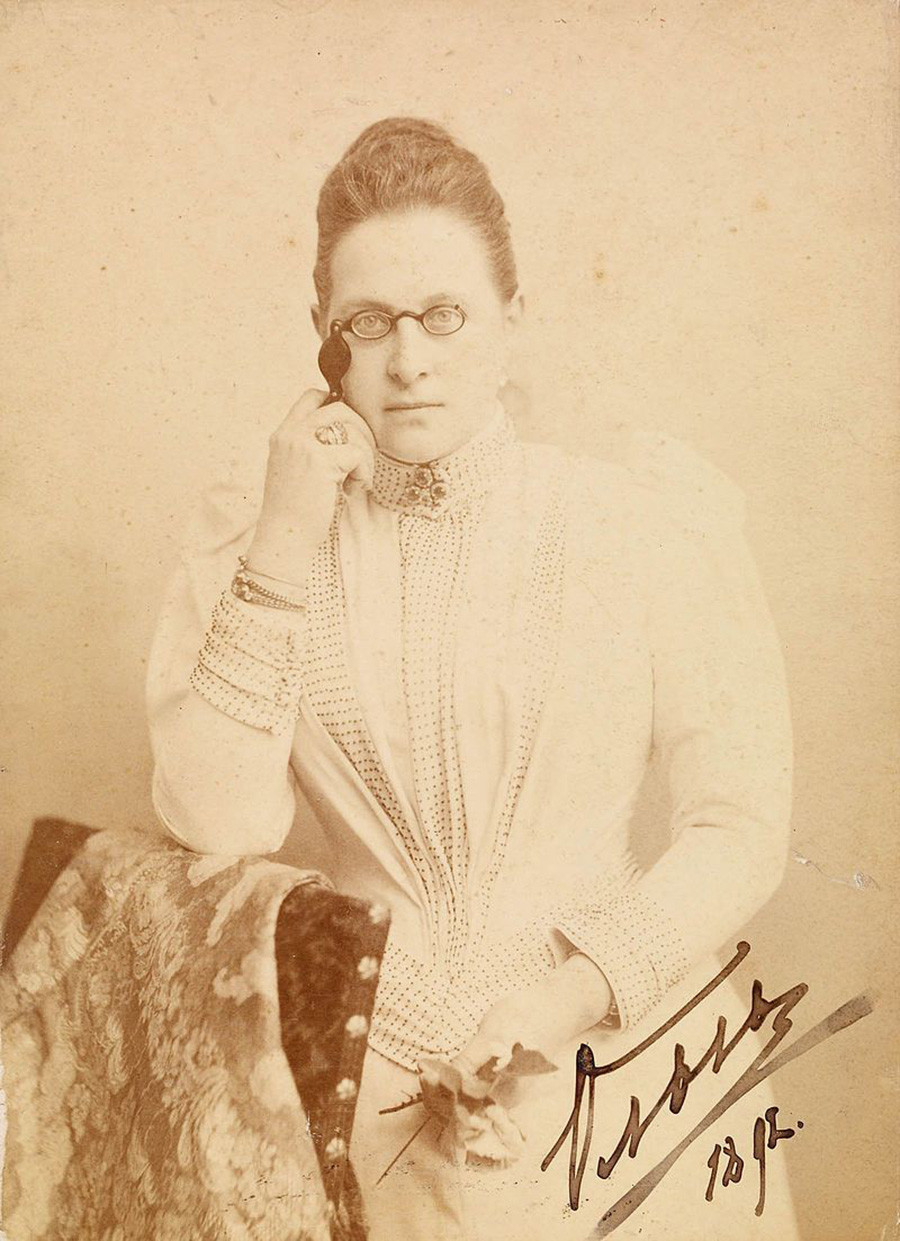

Grand Duke Nikolay Konstantinovich and his wife Nadezhda (nee Dreyer)

Public domainIn the second half of the 19th century, glasses finally became “acceptable”. Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich (1827-1892), Nicholas’s son and the head of the Naval Ministry, was the first Romanov who wasn’t afraid of being photographed in glasses. His unlucky son Nikolay Konstantinovich, the royal family’s outcast, wore glasses for most of his later life in exile. Many public persons and state officials, including Alexander Gorchakov, now, the Chancellor of Russia, wore glasses.

Grand Duchess Olga Konstantinovna using a lorgnette

Public domainHowever, some royal persons still considered glasses boorish – Alexandra Feodorovna, Nicholas II’s wife, had serious problems with eyesight, but she never was photographed or publicly seen in glasses or with a lorgnette. One of the rare photos of a Romanov using optics (a lorgnette) is the one of Olga Konstantinovna, grandmother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Olga Konstantinovna married George I of Greece (1845-1913) in 1867 and became a European royalty, so for her, a lorgnette wasn’t something to be ashamed of.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox