When in 941, Prince Igor, Rurik’s son, attacked the Byzantine capital of Constantinople with a fleet of about 1,000 vessels, the Byzantine fleet retaliated by using‘Greek fire’ – a flammable liquid mixture that was projected through tubes or catapulted in jars into enemy ships.

'Greek fire,' a medieval depiction

Public domain‘Greek fire’ was a deadly menace for the slow-moving, bulky ships of the era. Russian warriors preferred to drown than burn, and jumped off their ships. Igor’s fleet was devastated. “It is as if the Greeks had a lightning bolt from heaven, and by launching it, they burned us; that is why we didn’t overcome them,” Russian chronicles say.

It is believed that oil was the key ingredient of ‘Greek fire,’ and it was mainly obtained by the Byzantine Empire in the lands that are now Russia – Crimea and the town of Tmutarakan (Taman) in what is now Krasnodar region. Oil in those areas could be obtained from the surface of the Azov sea, or collected from oil and tar sands. Oil was obtained and stored for selling to the merchants of the Mediterranean region – archaeologists have found a lot of clay amphoras on the northern shores of the Sea of Azov.

Ancient amphoras used for oil storage, Taman peninsula

Archive photoSo, qualities of oil were obviously known to Russians in the medieval period. Fedot Kotov, a Russian merchant who traveled to Persia in 1623-1624, wrote: “Oil lamps are lit all around the square,” describing the city of Isfahan. Also, Kotov described a cult ceremony, during which “a straw man is brought to a field outside the city, then they... pour the oil on the straw man and burn it.”

Oil appearing in a hole bored through the ice of the Baikal lake, Russia

V. P. Isaev/Irkutsk State UniversityOil – which was called ‘stone oil’ in Russia – was traditionally used in painting and in medicine. A Russian manual for icon painters of the 17th century says: “When composing any paint, use wax, varnish, and add oil for it to dry faster. And when varnishing an icon, and it becomes thick, take a little oil with your finger and smudge it.” Oil was used as a paint solvent, and when drying, left a distinctive shine, so it was essential for icon painting.

Medicinal uses of oil included applying it for skin diseases, rheumatic diseases – currently in 2021, the effectiveness of oil for these purposes is scientifically proven.

Oil as a flammable material was used for other than military purposes, but on very special occasions – for “unquenchable” torches, or fireworks – both for royal gala ceremonies and festive occasions. And for warfare, oil was used in the making of grenades, ‘fire spikes’ and ‘fire cannon balls’ that the Russian army used in the 16th-17th centuries.

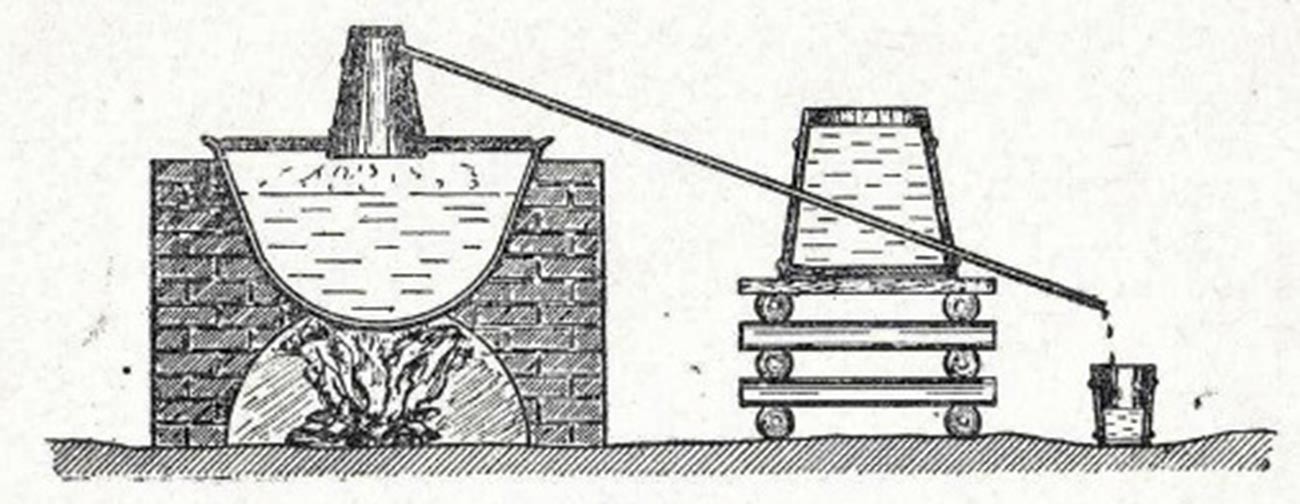

A scheme of an oil still

Archive photoIn 1650, records state that people living near Baikal lake collected oil from its surface – it oozed from the rocky shores of the rivers, went to the lake and the wind drove it to the shore, where it could be collected. This oil was occasionally transported to Moscow. In 1684, Leontiy Kislyanskiy, a state official in Irkutsk, Russian Far East, was sent to find oil deposits around the Baikal region. He reported about a hill that was really hot to touch, and that smelled of fresh oil. Kislyansky, who was a former painter and knew the many uses of oil, was planning to organize oil extraction, but was summoned to Moscow on other business – however, soon the state understood the necessity of oil production.

The Ukhta river, where oil deposits have been discovered

Borealis55While Tsar Peter was in his Great Embassy to Europe in 1697-1698, he met Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717), a Dutch statesman who was the mayor of Amsterdam. Witsen guided Peter in his journeys all over the Netherlands, they stayed friends and corresponded after. So Peter definitely knew that in his book ‘North and East Tartary,’ written after Witsen’s voyage to Russia with the Dutch Embassy in 1664-1665, Witsen described that somewhere on the river Ukhta, near the northern Russian town of Pechora, oil was being collected from the river’s surface.

In 1721, this place was discovered and samples of the Ukhta oil sent to St. Petersburg, but it wasn’t until 1745, when Fyodor Pryadunov, a Russian merchant and businessman, decided to open the first oil refinery plant there, and presented the oil he found to the Berg Collegium in Moscow, a state institution controlling mineral resources in Russia. Berg Collegium granted permission to start oil extraction and production.

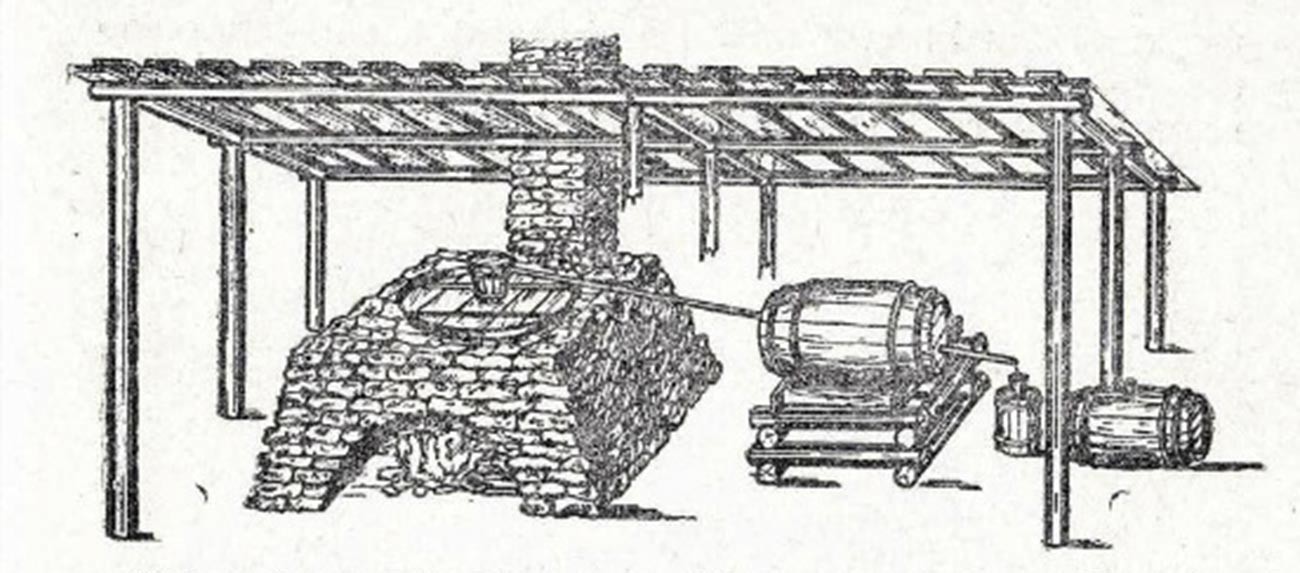

Fyodor Pryadunov's oil distillery

Archive photoThe first Russian oil well was just a log house situated on the river bed, close to the underground oil spring, collecting oil from water with the help of an inverted cone. The oil was also still collected from the surface. By 1748, Pryadunov had collected about 650 litres of oil and brought it to the Berg Collegium to be distilled. The results were impressive, but the problem was that nobody really needed distilled oil in Russia back then. In fact, Pryadunov distilled kerosene from oil, but kerosene lamps weren’t invented yet. So Pryadunov had nowhere to sell his oil.

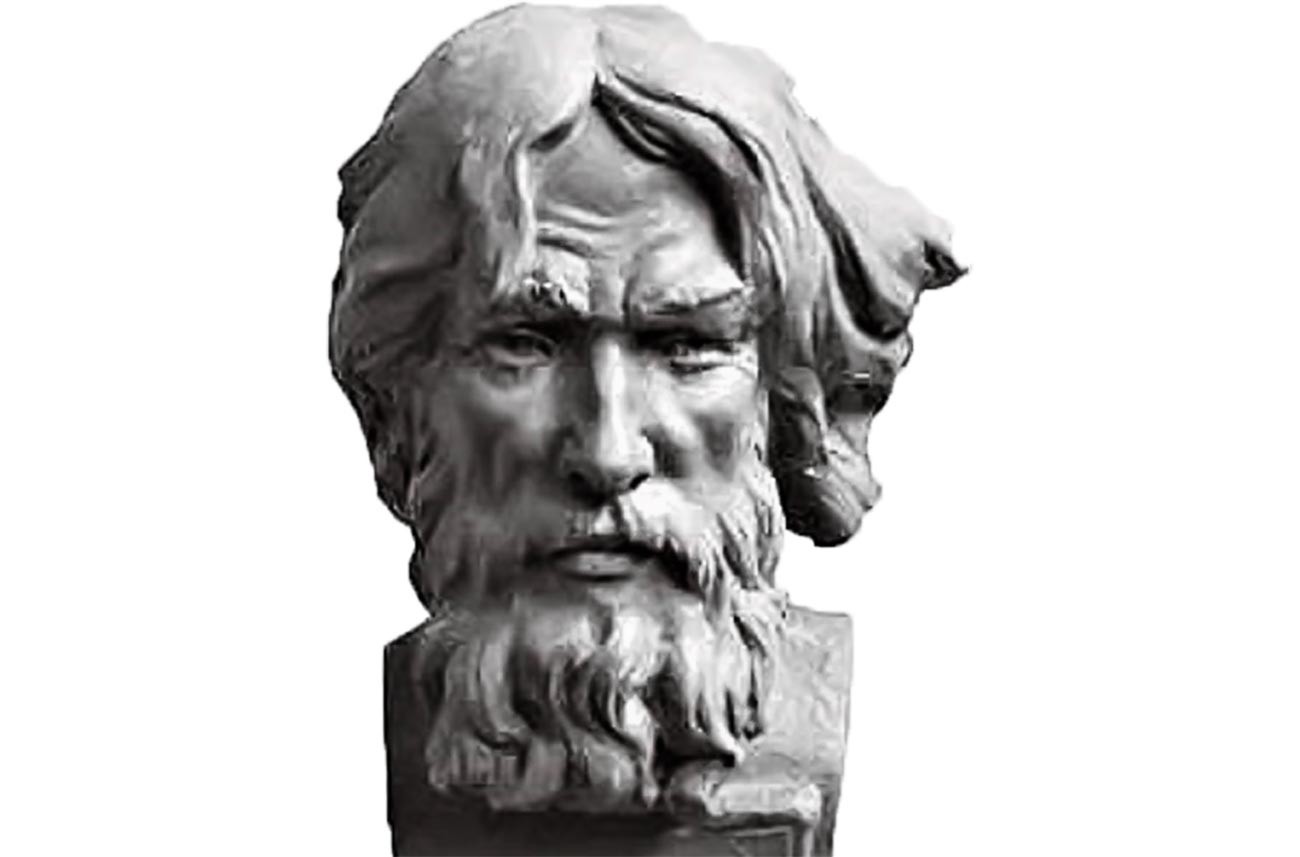

A reconstructed portrait of Fyodor Pryadunov

Public domainDesperate, Pryadunov sent oil samples to Hamburg for chemical testing and received in return a document signed by two German chemists that said the oil could probably be used for medicinal purposes - to aid patients “in cold and sputum, for dislocated joints, in fevers, in chills, for joint relaxation etc.” Pryadunov started selling his oil in Moscow as a new kind of medicine – illegally, without permission from the authorities. For this, he was arrested – and even after release, he was fined heavily and died in debt. His oil plant was destroyed by a river flood, and oil production largely didn’t resume in Russia until the 19th century, when vast oil deposits were put into production in the Caucasus, and the kerosene lamp was invented, but that’s another story.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox