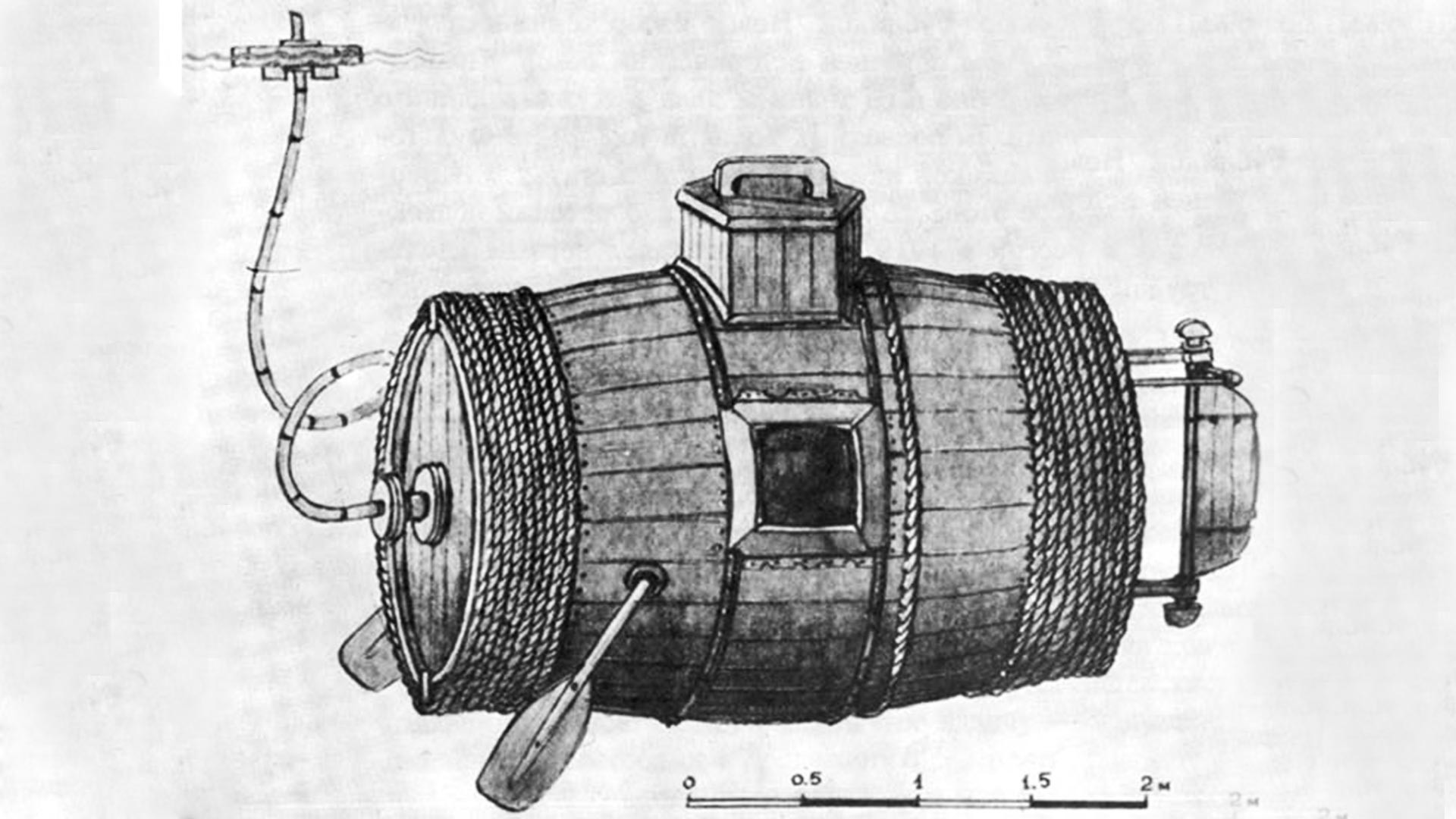

The layout of the “stealth vessel” in Sestroretsk, St. Petersburg.

Serguei Fadeev (CC BY-SA 3.0)In the early 20th century, submarines became an integral part of the armed forces of all the Great Powers. Russia, however, could have created a submarine fleet 200 years earlier. Why didn’t it?

The idea to build a "stealth vessel" capable of sailing underwater and “knocking a warship out from below” belonged to Yefim Nikonov, a simple carpenter who worked in a shipyard in the 18th century. He had no engineering background and was illiterate. But that did not stop him from being a master shipbuilder.

Nikonov sent numerous technical specifications (written down by others) to Peter the Great for a submarine that would “lie quietly under the waves then destroy warships, at least ten or twenty, with a projectile.” If it failed, he said, he was ready to answer with his head.

Peter the Great.

Nikolay DobrovolskyIn 1719, the tsar finally paid attention to the project and invited Nikonov to discuss the idea in person. Although the concept was by no means new (Dutch engineer Cornelius Drebbel had tested the world’s first submarine in the Thames in London back in 1620), Peter became transfixed by it. He appointed Yefim as his “master of stealth vessels” and gave him a workshop in St Petersburg and the right to choose his assistants.

Thirteen months later, a small prototype was tested in the Neva. Halfway across the river, the vessel submerged, then surfaced on the other side. The second dive did not go so smoothly, and the vessel failed to rise. The tsar, looking on, personally took part in the operation to raise the ship using ropes. Despite the failure, he ordered the construction of a full-fledged model.

Nikonov’s “stealth vessel” was completed in 1724. When entering it in the books, the clerk miswrote one letter, writing “Morel” instead of “Model”. The name stuck.

The first Russian submarine was shaped like a large wooden barrel six meters long, two meters high. It was fastened together with iron hoops and wrapped in leather.

Ten tin plates perforated with tiny holes were built into the body. Through them, outboard water flowed into leather bags, causing the vessel to submerge. On surfacing, the water was discharged overboard using a copper piston pump. The five-crewed submarine was powered by oars.

Morel’s main weapon was to be flamethrowers ("fiery copper pipes"). In addition, a diver would climb out and, using special tools, damage the hull of the enemy ship. Nikonov even designed a "diving suit" for this new profession.

In the spring of 1724, the "stealth vessel" was again tested in the Neva, once more in the presence of Peter the Great and naval officers. It successfully sank to a depth of 3-4 meters, but then scraped the ground with its keel.

The hermetically sealed Morel was ripped open, and the crew had to be urgently rescued. But despite this second failure, Peter refused to condemn either the vessel or its inventor, ordering that he "not be blamed for this discomfiture."

Monument to the “stealth vessel” tests in Sestroretsk, St. Petersburg.

Bogdanov-62 (CC BY-SA 4.0)However, the tsar’s death soon afterwards put paid to the ambitious project. The now patronless Nikonov had far less money, manpower and materials to play with.

The last “stealth vessel” tests took place in 1727. After another unsuccessful attempt, Nikonov was demoted from the rank of master shipbuilder to simple “admiralty worker” and sent from the capital to remote Astrakhan. As a result, Russia had to wait nearly two more centuries before acquiring its first submarine fleet.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox