Russia’s best-known square had many chances of developing a - sometimes radically - new look. It is now clear that it was only an accidental combination of circumstances that prevented the Red Square from turning into a giant necropolis in the middle of a field or the grounds of a huge memorial.

The first plan for the reconstruction of Moscow, including the Red Square, was proposed by the Bolsheviks immediately after the Soviet government moved there from Petrograd (present-day St. Petersburg) in 1918. They even started reconstructing some old buildings and building some new ones, but the work started for real only in the 1930s, with the adoption of the General Plan of Moscow.

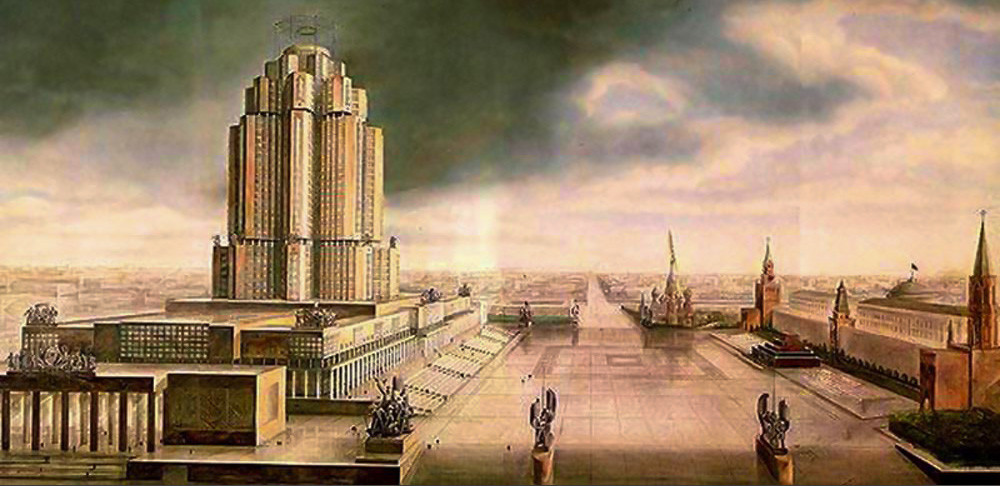

Narkomtiazhprom contest entry by Ivan Fomin Date 1934

Public domainProminent architects put forward their proposals for what Moscow as the capital of “victorious socialism” should look like. The most radical of them went as far as practically envisaging the creation of a completely new city on the site of the old one. In the end, a more moderate, but still quite large-scale, project was selected and, in 1935, the plan was adopted.

Moscow was to have more avenues than Paris, London or Berlin; a bigger administrative center than Washington DC; and the tallest skyscraper in the world. Under that plan, the historical center was to be demolished to free space for monumental buildings of national importance and the Red Square was to be expanded to double its present size.

GUM department store

Legion MediaA note to the General Plan read: “Moscow does not need the GUM department store. The Red Square, on which Lenin’s Mausoleum stands, is too cramped. It should be expanded at the expense of GUM.”

The list of casualties of that project would have included not only the famous GUM store, which had been standing in its spot since the 19th century, but also all the nearby buildings, including the Resurrection Gate. The square was to be renamed into ‘Mausoleum Avenue’ and consist of an empty space dominated by the House of Narkomtyazhprom, the building housing the People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry of the USSR. Under Stalin, it was one of the most influential departments, so the future project was dubbed “the Ministry of Ministries”. And its size should have left no-one in any doubt of its significance.

Another variant of House of Narkomtyazhprom

Public domainHowever, in the end, the gigantic skyscraper remained only on paper. Its implementation was prevented by the death in 1937 of the head of the People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry, a close ally of Stalin, Sergo Ordzhonikidze. According to the official theory, he died of a heart attack, while his wife and some contemporaries believed that he actually committed suicide.

One way or another, after Ordzhonikidze's death, the People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry began to lose its influence and was later broken into several independent ministries.

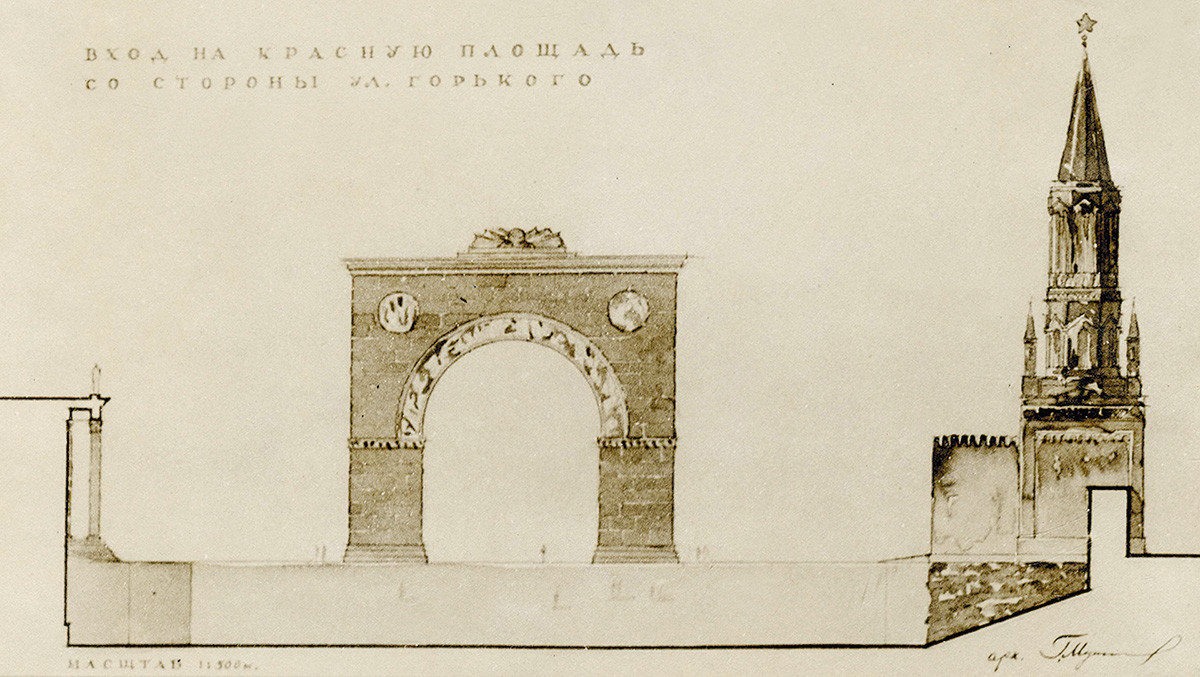

The second plan for revamping the Red Square emerged ten years later, in 1947. Circumstances had changed and the Soviet government was no longer thinking of gigantic ministry buildings. The Soviet Union had defeated Nazi Germany, which changed all plans. From now on, monumental architecture was to be used to celebrate one thing, the Victory.

As the most prominent location, the Red Square once again found itself the subject of ambitious plans for change and, once again, found to be too small. This time round the plan was to demolish GUM, all nearby low-rise buildings and the Historical Museum. In their place, there was to be a Victory Monument erected in the square with stands around it and a Victory Arch built at the site of the Historical Museum.

This is how the plan described it: “In order to create a grand entrance to the Red Square along the axis of movement of the demonstration columns, our project proposes to replace the building of the Historical Museum, whose bulky shape dominates the surroundings and hinders movement, with a Triumphal Arch of Victory, under which the victors will be marching to the square on Soviet holidays.”

Historical Museum

Legion MediaIn other words, the square was supposed to become a perfect venue for impressive parades on holidays, and nothing more.

These plans were, once again, upset by a death, this time, the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953.

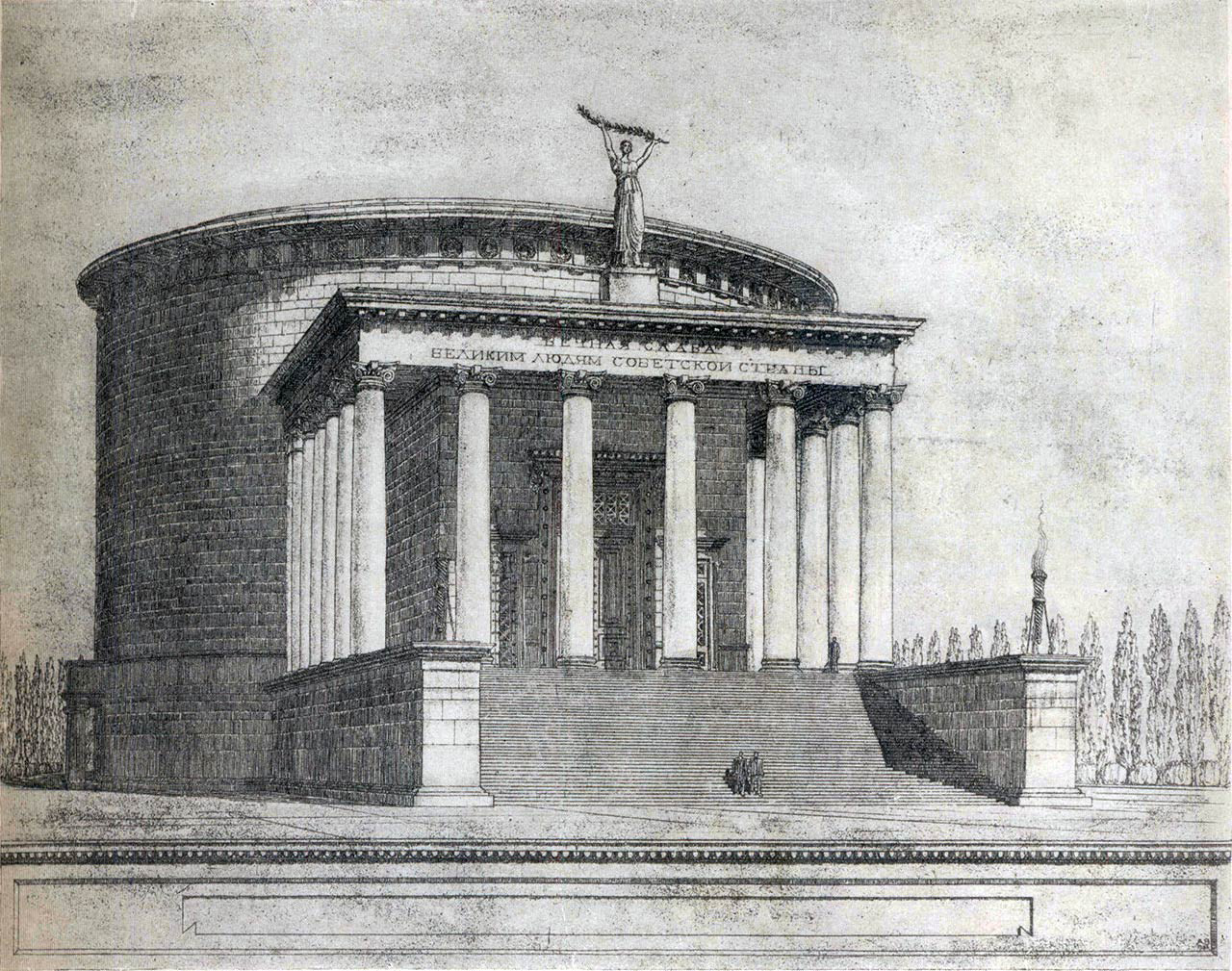

For seven years, the bodies of two Communist leaders - Lenin and Stalin - lay side by side in a very small mausoleum. Although, already on the next day after Stalin’s death, the party had issued a decree ordering the construction of a pantheon in Moscow.

Similar to Rome’s ‘Temple of All Gods’, the pantheon was to become a necropolis for Stalin, Lenin and all those “great people of the Soviet country” who were buried by the Kremlin wall.

Read more:How the Red Square almost became a NECROPOLIS for Soviet leaders (PICS)

To accommodate the necropolis, an area of 500,000 square meters (more than the size of the Vatican!) in the historical center was to be cleared of all buildings. The pantheon itself was supposed to stand next to the Kremlin, on the expanded Red Square, but there was one catch: the government stand on the pantheon would have been opposite from the existing mausoleum, so during parades columns of troops would have to march with their eyes to the right, which was against the established order. So, in the end, the square was left untouched.

The option of building the necropolis in another location too was abandoned. Nikita Khrushchev declared a war on Stalin’s personality cult and “architectural excesses” and put an end to this grand project.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox