In 1223, when the Mongol-Tatar army first invaded the Southern Russian lands, Prince Daniil of Galich (1204-1264), who was just 18, took part in the infamous Battle of Kalka.

The Galician–Volhynian Chronicle says that Novgorod prince Mstislav commanded Daniil and his regiment to attack the Mongols first: “Daniil went forth… and he was shot [by an arrow] into his chest, but because of his youth and fierceness, he didn’t feel the wounds on his body. For he was 18 and he was strong.” Although the battle was lost, Daniil managed to survive and retreat. He only felt his wounds when he stopped by a forest stream to drink.

Thirty years later, Daniil would be crowned “King of Russia” a title bestowed on him by the Roman Catholic Church. It would mark the first and the last time in history that a Russian prince would hold such a title. Who was Daniil? And why did he accept this title?

Bust of Daniil of Galich in Lviv, Ukraine

Legion MediaIn the 13th century, Galich was the westernmost territory of Kievan Rus – it controlled important trading routes that led to Hungary and Poland. Although not as big as Kiev, Galich rivaled it in terms of supplies and standard of living.

Daniil was the son of Prince Roman of Galich, “a restless warrior, notable for his horrible cruelty,” historian Dmitry Volodikhin writes, and inherited his fierce nature. Daniil was brought up far from home, at the court of his ally, the Hungarian King Andrew II (1175-1235), because at home, hostile princes of other principalities invaded Galich. For political reasons, when he became an adult, Daniil was allowed only to rule the principality of Volhynia that bordered Galich principality from the north.

But he was famous for his prowess in battle – that’s why he was the first to enter the battle at the Kalka river. A decade later, in 1233, Daniil took Galich back under his control in a series of conflicts with his peer princes.

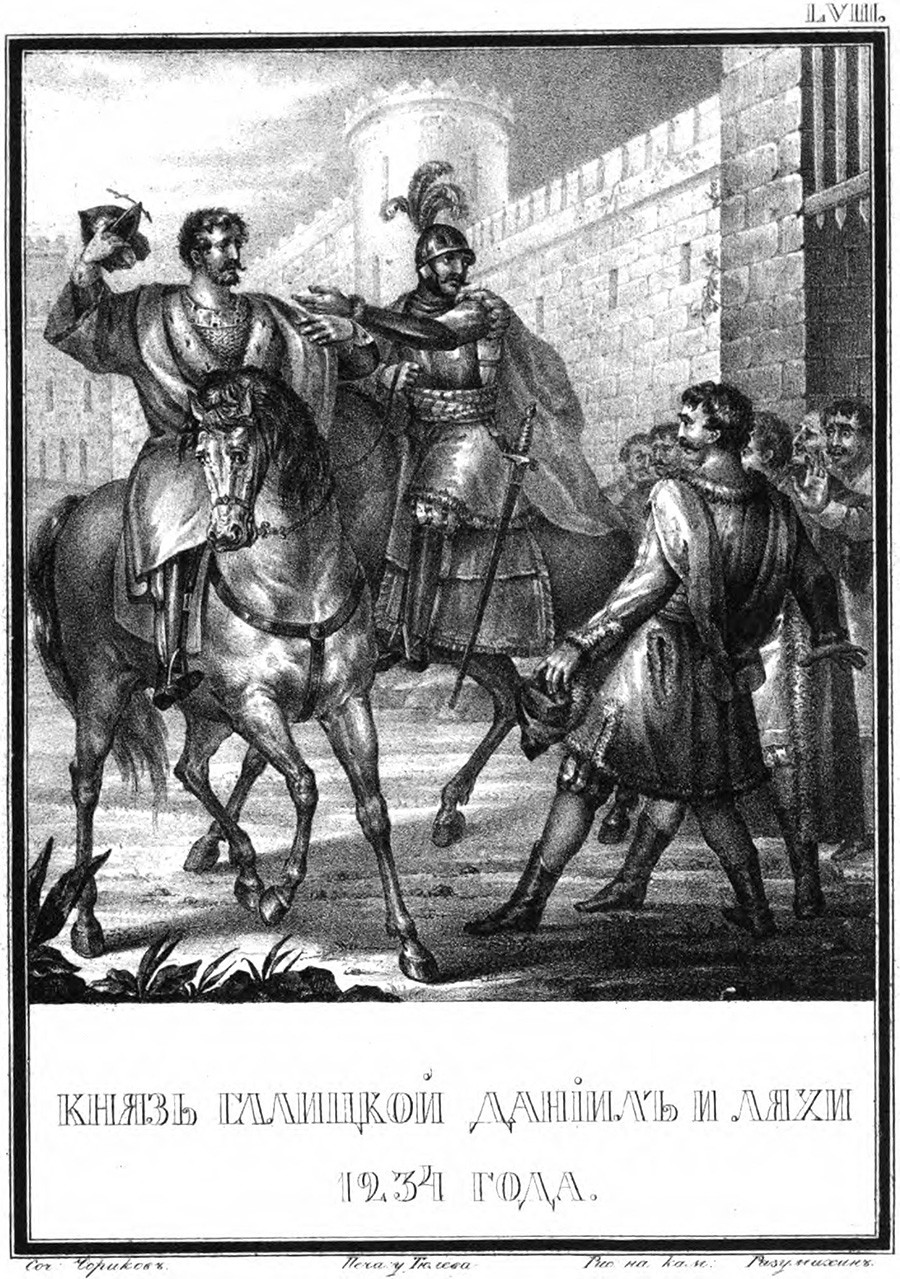

Daniil of Galich in 1234 (From Illustrated History of Russia by Nikolai Karamzin), 1836. Found in the collection of Russian State Library, Moscow

Getty ImagesDuring the 1220s-1230s, Daniil fought endlessly. As a war commander, he achieved well-deserved fame. In 1245, he united the Volhynian and Galich principalities under his control, and was one of the strongest Russian princes of the era. In choosing friends, Prince Daniil of Galich was guided by only one thing: his current political interests. He could get in a row with an ally and go to war on him, and the next day, support his former enemy, ask for his help, and a little later – break the alliance again.

By this time, however, the Mongol-Tatars had already subdued most Russian duchies. In 1239, they took neighboring Chernigov, in 1240 – Khan Batu personally led the Mongols on Kiev and took the ancient capital of the Russian lands, ravaged and plundered it.

A model of the ancient Galich. This is what the city could look like under Daniil's rule.

Roman ZacharijDaniil had to flee to Hungary – meanwhile, the Mongols took all the major cities of his land, including Galich – but then they left. By 1245, Daniil re-established control over his principalities and moved his residence from plundered Galich to the town of Chełm (now in Poland).

After a disastrous Mongol invasion, Daniil had to go to the Mongol-Tatar capital, Sarai, to swear his allegiance, which he did apparently with a heavy heart. However, Khan Batu himself treated Daniil with respect and even ordered wine to be served to Daniil – a rare gesture at a feast where everybody drank kumis (a fermented dairy product made from mare’s milk). But after returning from Sarai, Daniil still had plans to oppose the Mongol rule. “Recognising the Tatars’ was more evil than evil for him,” the Russian chronicle says of Daniil.

The monument to Daniil in Lviv, Ukraine

Legion MediaIt was on a trip to the Mongol capital where Daniil met Giovanni da Pian del Carpine (1185-1252), an Italian diplomat and archbishop, who first offered Daniil the idea of a church union. Subsequently, Pope Innocent IV (1195-1254) offered Daniil the title of “King of Rus’ (‘Rex Russiae’)” and agreed to provide military help against the Mongols in exchange for Catholicization of the Russian principalities and towns belonging to Daniil, which Daniil agreed to.

Pope Innocent IV (1195 - 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was the head of the Catholic Church from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Getty ImagesIn 1253, even before Daniil’s crowning, Innocent IV declared a crusade against the Mongols and summoned the Christian warriors of Bohemia, Moravia, Serbia, Pomerania, and Lithuania. However, even Daniil himself didn’t support the crusade then. Nevertheless, in 1254 he was crowned as the “King of Rus’” in the town of Drohiczyn. His royal residence was located in Chełm.

Unfortunately, Daniil didn’t really use his title at all. The promised help from Pope Innocent IV against the Mongols never materialised. Daniil, in turn, didn’t even declare the church union and the Catholicization of his lands. In 1254, Pope Innocent IV died, and the next Pope, Alexander IV (1185-1261) allowed the Grand Duke of Lithuania Mindaugas to wage war on Russian lands. After that, Daniil ceased all relations with the Diocese of Rome, retaining the title of “King of Rus’” for his own use.

A street in Chelm, Poland, Lublin Voivodeship.

Legion MediaAs for the Mongols, Daniil actually helped them against Lithuania. When in 1258, Mongol war commander Boroldai came to Rus’ with his army, Daniil sent his brother Vasil’ko with a substantial force along with Boroldai to plunder the Lithuanian lands. Again, it was only current interests that guided Daniil along his political path. He died in 1264 and was buried in his residence in Chelm. A Russian chronicle, mourning his death, calls him "the second [one] after Solomon."

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox