As of 2020, there were over 350,000people living in Russia who still held a Soviet passport as their main personal identification document. Mostly, they were pensioners or homeless people, who didn’t want to or couldn’t renew their passports. Formally, those passports are still active – no law in the Russian Federation has banned them. Soviet passports were not only documents, but symbols of Soviet citizenship. How did they appear?

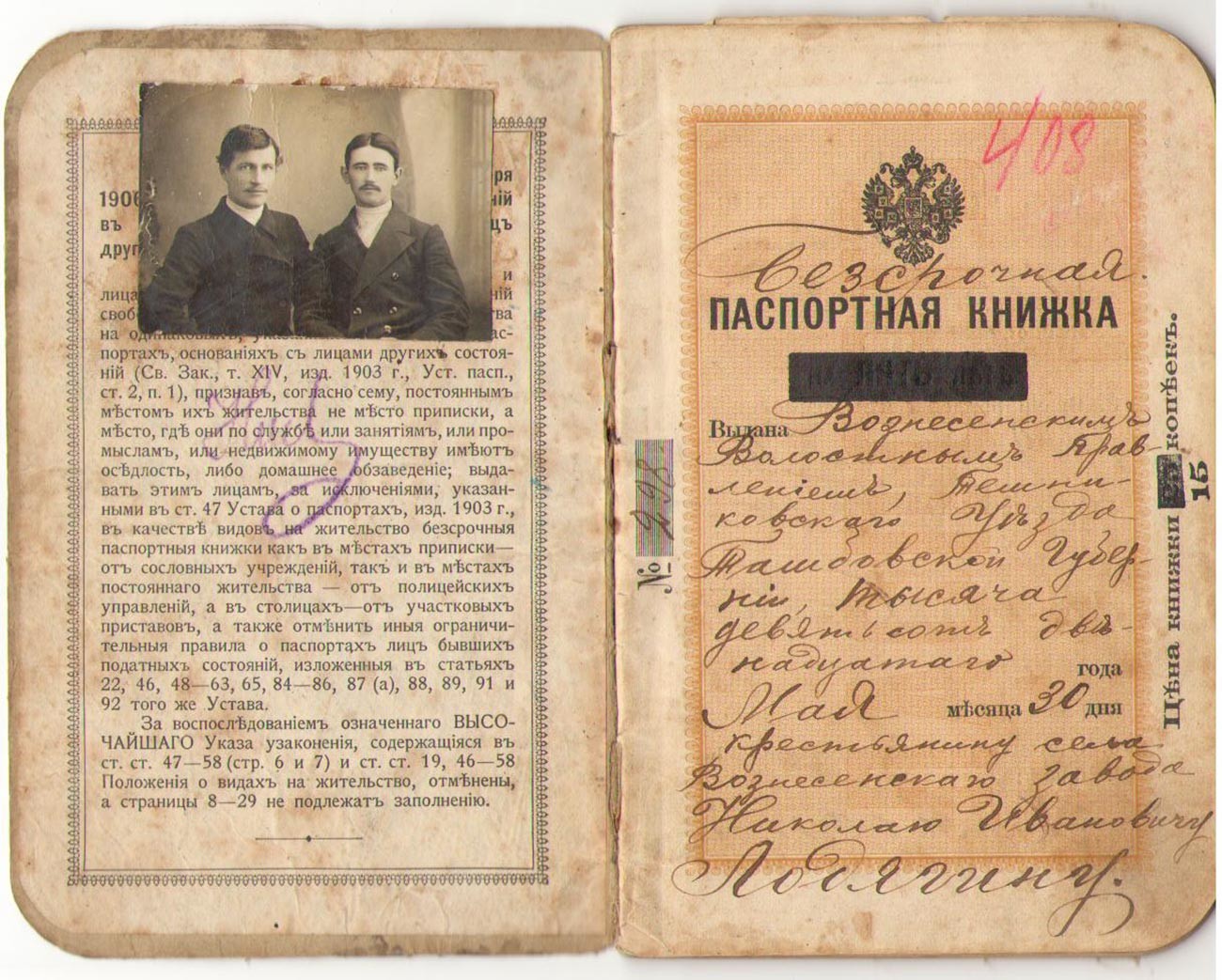

A passport of the Russian Empire

Archive photoThe first passports appeared in Russia in the 16th-17th centuries as documents for foreign envoys and merchants. Peter the Great introduced internal passports to control the vast internal migration ignited by his reforms.

The state wanted to know where its tax subjects were, so peasants, merchants and townspeople needed passports to move across Russia. Those peasants who left their place of residence to work in other parts of the country, would have had passports that described their appearance. Nobles could travel without passports, but had to acquire a podorozhnaya – a special document for the use of a state-owned horse and cart while traveling. Podorozhnayas also helped the government control the movements of its subjects.

A podorozhnaya, travel document

Archive photoBy the end of the 19th century, all Russian people had residence permits recorded at local police precincts. They were not allowed to leave their place of residence for more than six months at a time. The Bolsheviks used this in their anti-Tsarist propaganda. In 1903, Lenin wrote: “The Social Democrats demand complete freedom of movement and trade for the people – to destroy the passports… The Russian muzhik is still so enslaved by officials that he cannot freely move to the city, nor can he freely go to new lands. Isn't this serfdom? Isn't this an oppression of the people?”

With the Revolution of 1917, the old passport system was banned – the documents issued by the Russian Empire were declared null and void by 1923. However, a state could not function without a system of records about its citizens. Anthropologist Albe Bayburin stated in a lecture that the absence of passports “led to disastrous confusions with distributing food stamps, not to mention military accounting and statistics of the working-age population.”

The 1920s were an age of industrialization and collectivization. Huge numbers of people were relocated and impoverished. There were food shortages and bad housing conditions, and people flocked to big cities to find a place to live and work. In these conditions, the Bolsheviks had to re-introduce the passport system. Its main function was actually to separate ‘good’ citizens, that were profitable for the state, from ‘bad’ citizens – former Tsarist officials, cops and soldiers, and most of all, the former nobility.

There were a great number of categories of people who were not allowed to have Soviet passports. Unemployed people, former kulaks (wealthy peasants), priests and members of the clergy, all former Tsarist officials, policemen, judicial officers – they weren’t allowed to have passports. So these vast numbers of people had to conceal their background or find some way to get a passport to live in the cities.

In the countryside, former peasants, now workers of kolkhozes (collective farms) didn’t have passports until the 1970s-1980s. Why? In 1949, the Bureau of the Council of Ministers discussed a project to issue passports to all people over 16 – but somehow, the reform was put on hold. For the kolkhoz workers (former peasants), absence of a passport meant inability to move and find work away from their place of residence. Meanwhile, in the 1920s, about 80% of the Soviet population were living in the countryside (however, not all of them were kolkhoz workers). Migrating to the cities, the former rural people got their passports and residence permits, but by 1974, still about 20% of the population were 'passport-less.'

The passport of Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Executive Committee of the Communist Party of USSR

Archive photoThe Soviet passport had very good publicity with Vladimir Maykovsky’s poem “My Soviet Passport,” written in 1929: “I pull out of my wide trouser-pockets duplicate of a priceless cargo. You now: read this and envy, I'm a citizen of the Soviet Socialist Union!” All Soviet schoolchildren were obliged to learn this by heart, even in the 1990s, after the end of the USSR, and so the red-skinned passport with a hammer and sickle on it was perceived as a sacred document of a Soviet citizen.

The passports were introduced on December 27th, 1932: “All citizens of the USSR at the age of 16 years, permanently residing in cities, working settlements, working on transport, in state farms and on building sites, are required to have passports,” the resolution of the Soviet government said. The Soviet passport was an all-definitive document: it had ‘nationality’ column, it contained registration stamps (in the USSR, known as propiska), the marital status of its owner, his social status (worker, collective farmer, individual peasant, employee, student, writer, artist, sculptor, artisan, pensioner, dependent, without certain occupations – these were the ‘categories’), place of employment or study.

Elena Gagarina, daughter of Yuri Gagarin, receives the passport of a Soviet citizen.

Alexander Konkov/TASSCriminal records were also ‘stamped’ in passports, and it was almost impossible to find a decent job for a person whom the Soviet authorities classified as a “criminal element”. So, Soviet passports were documents ideal for the oppression of their carriers – the Soviet state, just as the Russian Empire, wanted total control and supervision of its subjects.

The instructions for Soviet militia dating back to 1935 defined the main tasks of the militia in maintaining the passport regime in the USSR as follows: preventing residence without a passport and without a residence permit (propiska); preventing employment or service without passports. From 1937, passports had photos – exact copies of these photos were stored in files in institutions called ‘passport tables’ that controlled the issuing of the passports.

Finally on August 28th, 1974, the decision to issue new Soviet passports was made, and also, to give passports to all Soviet citizens 16 years old or older, without exceptions – this time, finally, the Soviet peasants got their passports. In 1976-1981, all passports were replaced with new ones. The new law also forbade placing any marks or stamps in passports – however, the stamps about criminal restrictions were still made by the local authorities and police.

The last Soviet passports were in use until 1997, when the new Russian passport was created. But, there was no particular law that banned the usage of Soviet passports – so formally, they’re still valid as a document.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox