In the 1930s-40s, it was not safe to tell jokes about the leaders of the Communist Party or, God forbid, about Stalin himself. Such jokes were regarded as a crime under a provision of “Anti-Soviet propaganda and counterrevolutionary jokes” and could land the joker in a prison camp for between six and 10 years (!) and, in time of war, he or she could pay with their life.

For instance, a certain Sergei Popovich was imprisoned for 10 years for telling the following joke:

“An old lady sees a camel for the first time in her life and starts to cry. ‘Oh, poor horsey, what did Soviet power do to you…!’”

Those who listened to anti-Soviet jokes could also be punished, unless they reported it to the security authorities. Otherwise, they faced up to five years in a prison camp under the provision, “For failure to inform the authorities”.

In the USSR from the late 1930s, almost all martial arts were strictly prohibited (apart from sambo, wrestling and boxing) and their adherents were declared to be “spies”, usually Japanese ones. But, karate enthusiasts were particularly unlucky. In 1981, a special article regarding them even appeared in the Criminal Code - under it, those who coached karate were subject to five years behind bars! The reason was given as follows: “Karate is a form of hand-to-hand combat which has nothing in common with sport, which cultivates cruelty and violence, which inflicts severe injuries on its practitioners and which is permeated with an ideology that is alien to us.”

True, only one person was ever convicted under this provision - it was decided to make an example of 33-year-old Valery Gusev, a famous Soviet coach who, according to investigators, secretly coached students in urban woodlands for a fee. In actual fact, he taught kung fu, not karate, but the law-enforcers didn’t see much difference between the two. Later, in an interview with the Moskovsky Komsomolets daily newspaper, Gusev would say: “It was really a show trial - they had been specially looking for a well-known person <...>. Or it might all have happened to me because, shortly before my arrest, I had flatly refused an offer (albeit, unofficial) to work as a coach for the KGB. There might have been some ill-wishers in high places, or perhaps I had crossed someone’s path.”

The danger of being convicted for karate didn’t last long, however - with the advent of perestroika in 1989, the law was abolished.

In 1922, the Soviet state decriminalized homosexual relationships. The law imposed punishments only for rape, corruption of minors, procurement and enlistment into prostitution, regardless of gender. But, in 1933, People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs of the USSR Genrikh Yagoda, in a report to Stalin, linked homosexual proclivities to counterrevolution - gays had allegedly turned their clubs into centers for “corrupting young people” and were leading them astray (including in the political sense).

So, a year later, a new article was added to the Criminal Code prescribing imprisonment of up to five years for homosexual relations. Furthermore, only men were prosecuted under the provision, which didn’t apply to women. As far as is known from the archival research of Professor Vladimir Volodin, starting from the 1960s, about 1,000 men were convicted under this provision in the USSR every year and guilty verdicts reached their peak in 1985 (there are no openly available statistics on those convicted - Ed.).

At the height of the Third Five-Year Plan, in 1940, volumes of industrial production needed to be sharply boosted and the war that had started in Europe made it necessary to optimize military supplies. To give a spur to output, authorities brought in a seven-day working week, made it illegal for workers to leave the premises without a manager’s permission, to fail to turn up for work or to be late.

Quitting a job without permission could attract a custodial sentence of 2-4 months. Coming in 20 minutes late, returning late from a lunch break or not turning up for work at all could be punished by corrective work [at the place of employment] and, if repeated, by a custodial sentence. In less than three months after the new regulations came into force, almost one million people were sentenced in this way across the country.

Soviet propaganda described the USSR as a state of social equality and justice - consequently, the existence of beggars, the homeless or the unemployed was completely incompatible with this basic premise. Such people did, of course, exist, but they were simply removed from the streets. A decree “On measures to counter anti-social and parasitic elements” was promulgated in 1951, under which anyone homeless had to be sent for special resettlement in distant parts of the USSR for five years. It meant banishment, for all intents and purposes.

Ten years later, things became even stricter and criminal prosecutions for “sponging” (ie. not having an official job, also referred to as “social parasitism”) were brought in. It wasn’t just the homeless who fell victim to this campaign, but also anyone with unofficial income. For the absence of a roof over your head or of official employment, you could be thrown into jail at any moment - for up to two years. A term in prison was an occupational hazard for private taxi drivers, builders, musicians and so on. The well-known poet Joseph Brodsky was charged under the “social parasitism” provision, while Viktor Tsoi, a popular singer in the 1980s, found work as a boiler attendant just to be able to declare it as his “official job”.

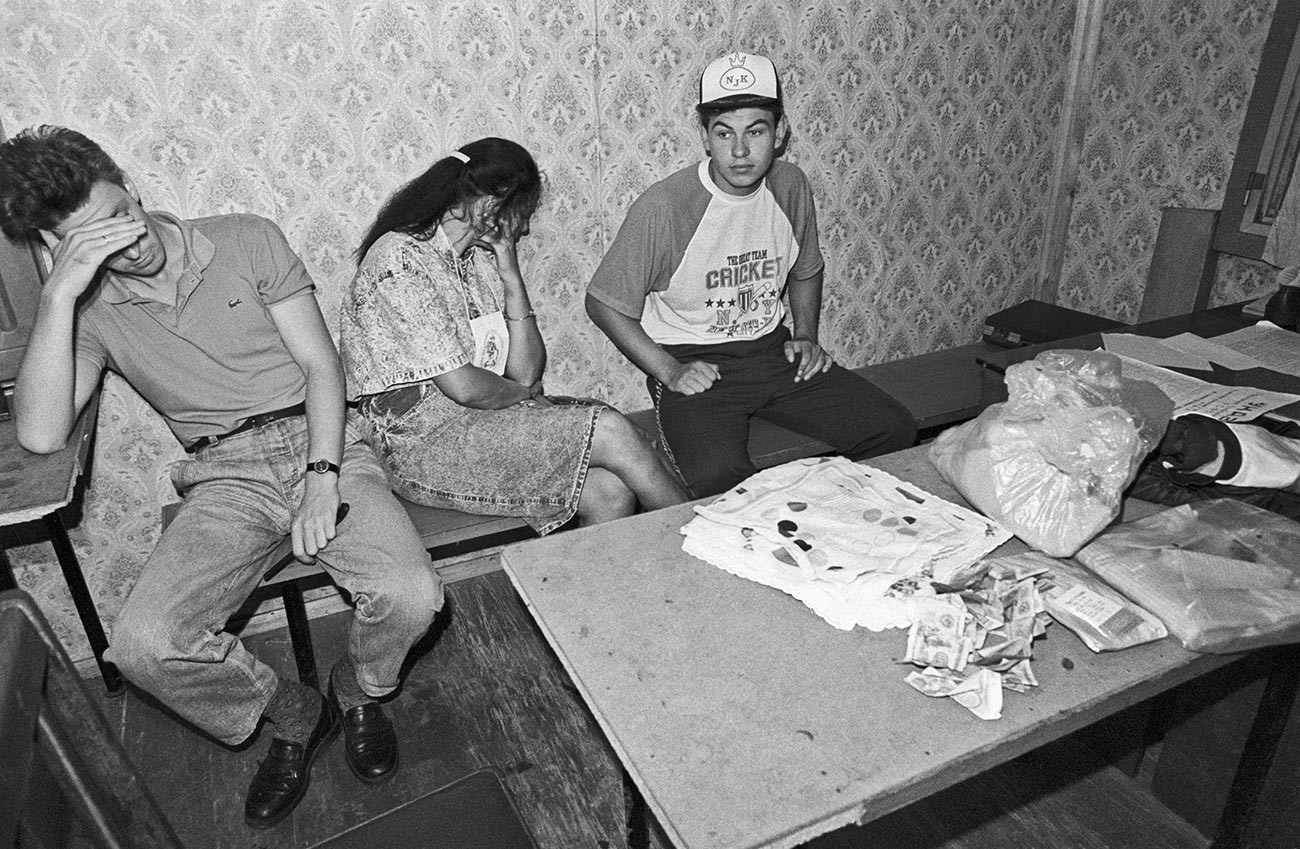

Black marketeering - the process of acquiring and reselling foreign goods - was also outlawed, even though, in the 1980s, it was a thriving business. If Soviet citizens wanted to obtain something foreign made - something “chic”, as it was known - there were only ever two ways of going about it: traveling abroad (something only rare individuals were allowed to do) or buying it from a black marketeer.

Black marketeers were mainly enterprising young people and also those who came into regular contact with foreigners through their line of work: guides, translators, taxi drivers, prostitutes plying their trade for hard currency in hotels for foreigners, etc. They might negotiate a couple of spare packs of Marlboro cigarettes or a pair of Levi’s jeans from foreigners, which they then sold on to their fellow citizens with a large mark-up. Despite the secrecy in which such deals were conducted and the clandestine meetings held behind garages, black marketeers were sometimes caught and sentenced to up to seven years. Penalties for this sort of activity were, however, also abolished in 1991.

Soviet citizens were “cut off” from foreign currency in 1927, when the Bolsheviks banned the private exchange market and imposed a state monopoly for foreign exchange (you can read about the reasons for this here). Ten years later, under Stalin, selling currency privately became a potentially lethal activity: A new criminal charge equating currency transactions with crimes against the state was brought in. And in 1961, Article 88 came in, prescribing penalties from three years imprisonment to the death penalty (by shooting) if the scale of the “offence” was particularly large.

The Stalinist ban and the “death by shooting article” for illegal possession of hard currency remained in place until 1994.

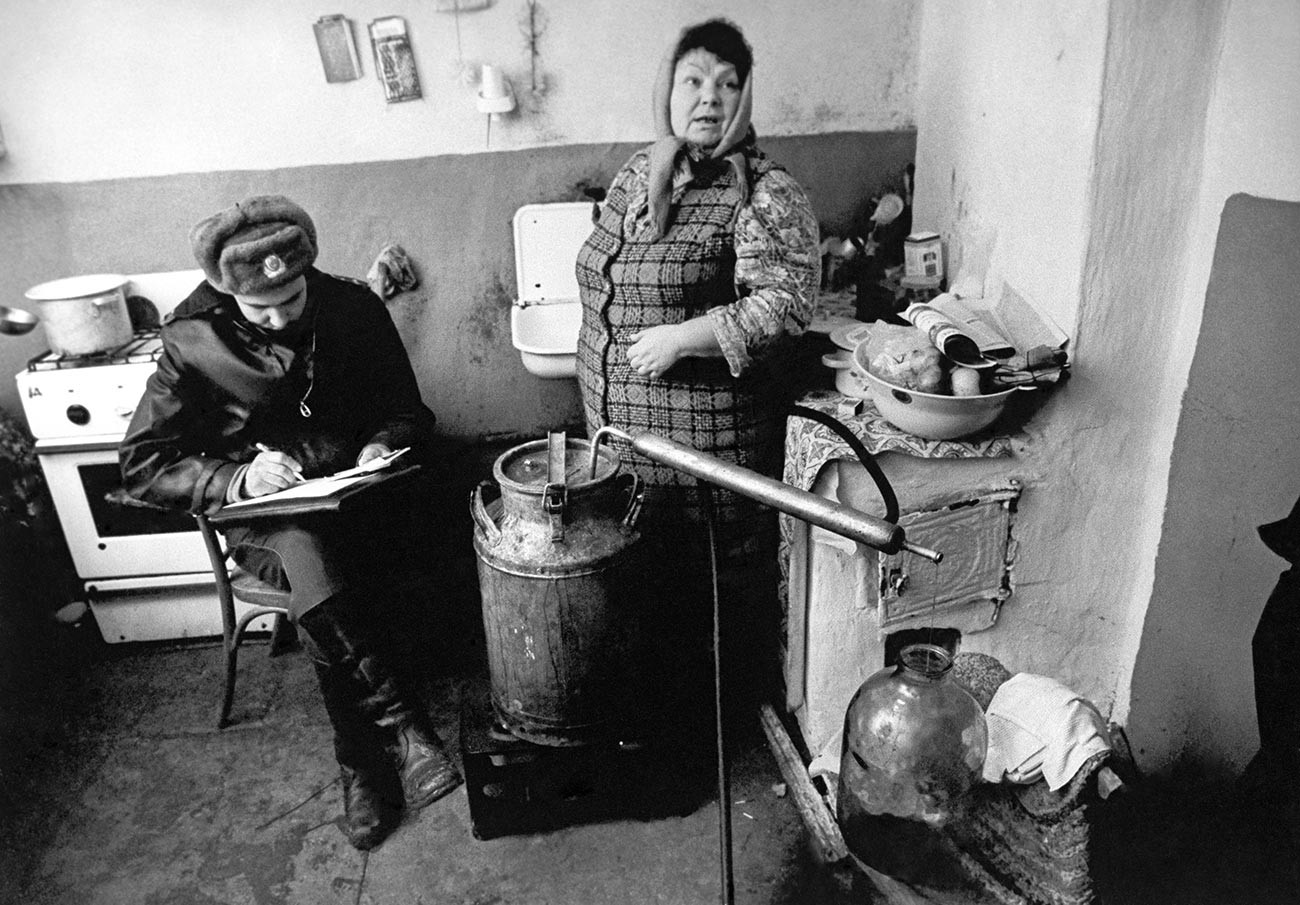

Many households in the Soviet Union knew how to make alcohol at home, even in small apartments in urban high-rises and not just in the countryside. But, the anti-drinking campaigns regularly mounted by the authorities always took a heavy toll on home distillers. For instance, 52,143 people were convicted of making or selling moonshine in 1958 alone. There were sentences of 6-7 years for anyone making money out of the sale of this kind of alcohol and 1-2 years in prison for those who made it for personal use. Just for being caught with a still for making alcohol at home people faced six months of corrective labor or a hefty fine.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, home distilling ceased to be a criminal offence and, since 2002, it hasn’t even been an administrative one.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox