The moment Prince Mikhail Golitsyn fell head over heels for an Italian girl on a trip to the Meditarannean, little did he know this passion-fueled affair would change his life forever - though not for the better.

The relationship was problematic for several reasons. Mikhail’s new wife, like most Italians, was Catholic. This meant she only agreed to marry him on the condition that he renounce his Russian Orthodox faith - the faith of the Romanovs - and pledge fealty to the Pope of Rome.

The fact that Mikhail renounced his faith in the name of love did not sit well with his empress, Anna Ivanovna. In the eyes of the czarina, a control freak with a hot temper, who also happened to fancy herself an expert matchmaker, abandoning the Russian Orthodox faith was unacceptable for a man of Golitsyn’s status.

As soon as it was in Anna’s power to do so, she would punish him for following his heart.

Portrait of Anna Ivanovna by an anonymous painter (1670s-1917)

HermitageAnna Ivanovna, born in 1693 to Czar Ivan V, had a complicated love life. Like most young girls, especially young girls of royalty, she was beyond excited when her family married her off to Frederick William, the Duke of Courland. At the tender age of seventeen, she wrote the Duke that “nothing could delight me more than to hear your declaration of love for me”.

Unfortunately for Anna, the Duke died on their way back to Latvia. Although historians continue to debate the exact cause of his death, they all agree that the Duke was a very heavy drinker and that he and Anna’s uncle, Peter the Great, may have had a few too many during the former’s wedding celebrations back in Petersburg. Both Anna and Duke were very young by modern standards, 17 and 18 years old, respectively.

Stranded in a strange country, the widowed Anna wrote her family hundreds of letters, begging them to find her a new suitor. Every single request was duly discarded by Peter. Presumably, because he disliked his niece’s temperament. Possibly, because he wanted to prevent her from producing heirs that could compete with his own. But most definitely because he wanted her to remain in control of Courland, which Russia would have to release in case Anna remarried.

After several years of trying and failing to find a new husband, Anna resolved to remain single. While she greatly enjoyed playing matchmaker for her subjects, she was also embittered and intensely jealous of anyone who had managed to find that which she had been denied: love.

All the same, Anna had the last laugh. When Peter the Great’s grandson, Peter II, died without ever fathering a single child, it was Anna who ascended the throne of Russia. The Supreme Privy Council, an executive body made up of wealthy families, crowned her czarina in the hopes that she would be easy to control.

But, as the story of Prince Mikhail illustrates, they were wrong.

After Anna cancelled Mikhail’s wedding, the Italian woman was either exiled or deported. Although Mikhail was devastated, the czarina did not take pity on him. Upon his return to Petersburg, she stripped him of his land and title and made him her new fool.

From here on out, Mikhail was to be referred to by his first name and his first name only. Even when mentioned in official government documents. He spent his days crouching in a basket next to Anna’s desk and pouring her cups of kvas. According to some sources, the basket he sat in was filled with eggs, which he would pretend to lay to entertain guests.

And that was only the beginning. Being the matchmaker she was, Anna quickly set out to find her princely fool a new bride. She considered several maids in her service as contenders and ended up picking the ugliest among them: a stooped, young woman of Kalmyk descent named Avdotya who, according to the historian Henri Troyat, “was so ugly that even the priests were afraid of her.”

Valery Jacobi, ‘The Court Jesters of Anna Ivanovna’ (1872)

Tretyakov GalleryTheir wedding ceremony was to be a celebration of saturnalian proportions. On February 6, 1740, the unhappy couple - dressed in clown’s attire - were blessed inside a church. Next, they were hoisted on top of an Asian elephant. Tailed by a caravan of ambassadors from every race of the Russian Empire, Mikhail and his Kalmyk bride marched to their new “palace”.

This palace was, as you might have guessed, made entirely of ice. It was a record-breakingly cold winter in Russia that year, and the mighty Neva River had completely frozen over. On Anna’s orders, military personnel spent days hauling blocks of ice from the riverbank. These were then used to build the castle.

The end result of this seemingly impossible construction project was lauded as both a demonstration of magic and the work of science. The palace was 60 feet wide and 30 feet high. Inside was a staircase, balustrade and vestibule. Colonnades were decorated with precision-carved statues. All made of ice.

Valery Jacobi, ‘Ice Palace’ (1878)

State Russian MuseumAs was everything inside the master bedroom, from the pillows and mattresses to the bedframe and even the curtains hanging by the windows. Mikhail and Avdotya had just a few seconds to take it all in before they were locked inside. Guards barricaded the door and the Czarina - when leaving - urged the fool to consummate his marriage before he froze to death.

Satisfied with the feast she had organized, Anna retreated to her own palace made of stone and wood. Did she feel any remorse as she lay in a warm bed next to a fire, whilst her fool and his bride were freezing outside? “If any hint of it flitted through her mind,” wrote Troyat in his book, Terrible Tsarinas, “it must have been driven out very quickly by the thought that this was very much in line with the liberties allowed to any sovereign.”

With little to no narrative tinkering involved, the story of the ice palace and the jealous queen who built it seems to unfold much like something from a fairy tale. Fortunately, like any fairy tale, it too has a happy ending.

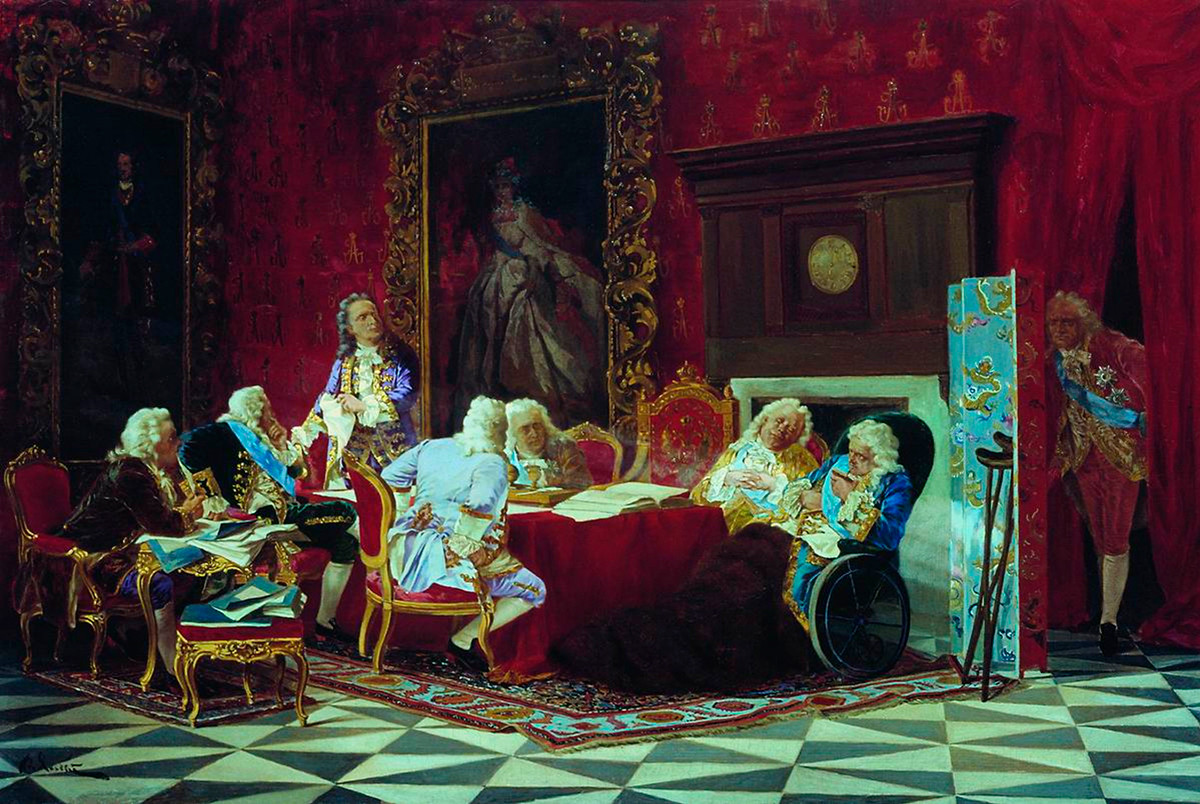

Valery Jacobi, ‘Cabinet Ministers of Anna Ivanovna’ (1889)

The Omsk Regional Museum of The Fine ArtsAs night settled over Petersburg, it did not take long for the imprisoned Mikhail to fall ill. His clown clothes might have prevented frostbite, but the couple had been forced to strip naked before they were locked in the bedroom. Without any protection from the elements, the feverish Mikhail began to drift in and out of consciousness.

Noticing her husband was in danger, Avdotya performed an incredibly noble act. She offered one of the guards the only thing she had on her at the time: a pearl necklace. Given to her by the czarina as a wedding gift, it was the most expensive item she had ever possessed - and she traded it for a fur coat.

The coat kept the couple warm throughout the night. As a result, they emerged the next morning with, in the words of Troyat, “nothing worse than a runny nose and some frostbite.” Mikhail and Avdotya were then freed from their servitude as jesters by Anna Leopoldovna, Anna’s successor. The couple remained married and Avdotya died in 1742 giving birth to their second child.

As for Anna herself, she died in 1740 from complications brought about by kidney stones. At the time of her passing, her ice palace had long melted. For many people, the mythical structure serves as a testament to the wrath of a larger-than-life historical figure. For historians, it’s a symbol of the queen’s limited power, defied by love.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox