Berlin residents saw Russian soldiers entering their city for the first time in history on Oct. 9, 1760, during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). Back then, the city was the capital of the Kingdom of Prussia, which found itself opposing the combined forces of Austria and Russia.

Vienna and St. Petersburg were extremely concerned about the aggressive policies of the Prussian king, Frederick II, who had transformed the once small principality into one of the most bellicose states on the European continent. War was only a matter of when.

The Prussian capital could in fact have been taken earlier, in 1759. On Aug. 12 of that year, the allied forces defeated the army of King Frederick at the Battle of Kunersdorf. However, instead of marching on the undefended Berlin, they headed in the completely different direction of Cottbus. The amazed and relieved Prussian monarch proclaimed this incident as "the miracle of the House of Brandenburg."

The next year, however, nothing could save the city. In early October, the 20,000-strong corps of Russia’s General Zakhar Chernyshev and the 15,000-strong force of Austria’s General Franz Moritz von Lacy advanced on Berlin.

The first onslaught of the approaching Russian troops the Germans managed to repel, but soon the Austrians appeared in the southern outskirts. The Prussians retreated without a fight, and on October 9 the victorious allies entered the city.

Gottlieb von Totleben, a Russian general of Saxon origin, demanded from the city the considerable sum of 1.5 million thalers, in addition to seizing all the royal manufactories and arsenal as trophies. He did not, however, permit the city to be plundered, as the embittered anti-Prussian Austrians were seeking to do. “Thanks to the Russians, Berlin was spared the horrors that the Austrians were threatening to inflict on my capital,” Frederick II would later say.

The Russian-Austrian occupation of Berlin lasted only three days, however. Upon learning that 70,000 fresh troops under the Prussian king were advancing in their direction, the two allies speedily withdrew from the city on Oct. 12, 1760.

After Napoleon’s Grande Armée ran aground in Russia in 1812, Russian troops embarked on a continent-wide campaign to liberate Europe from the clutches of the “Corsican ogre.”

One of the first states on their way to Paris was the Kingdom of Prussia. Having lost almost half of its territories after a string of heavy defeats in 1806, the kingdom was effectively a French vassal. As such, Napoleon's force that invaded Russia counted tens of thousands of Prussian soldiers.

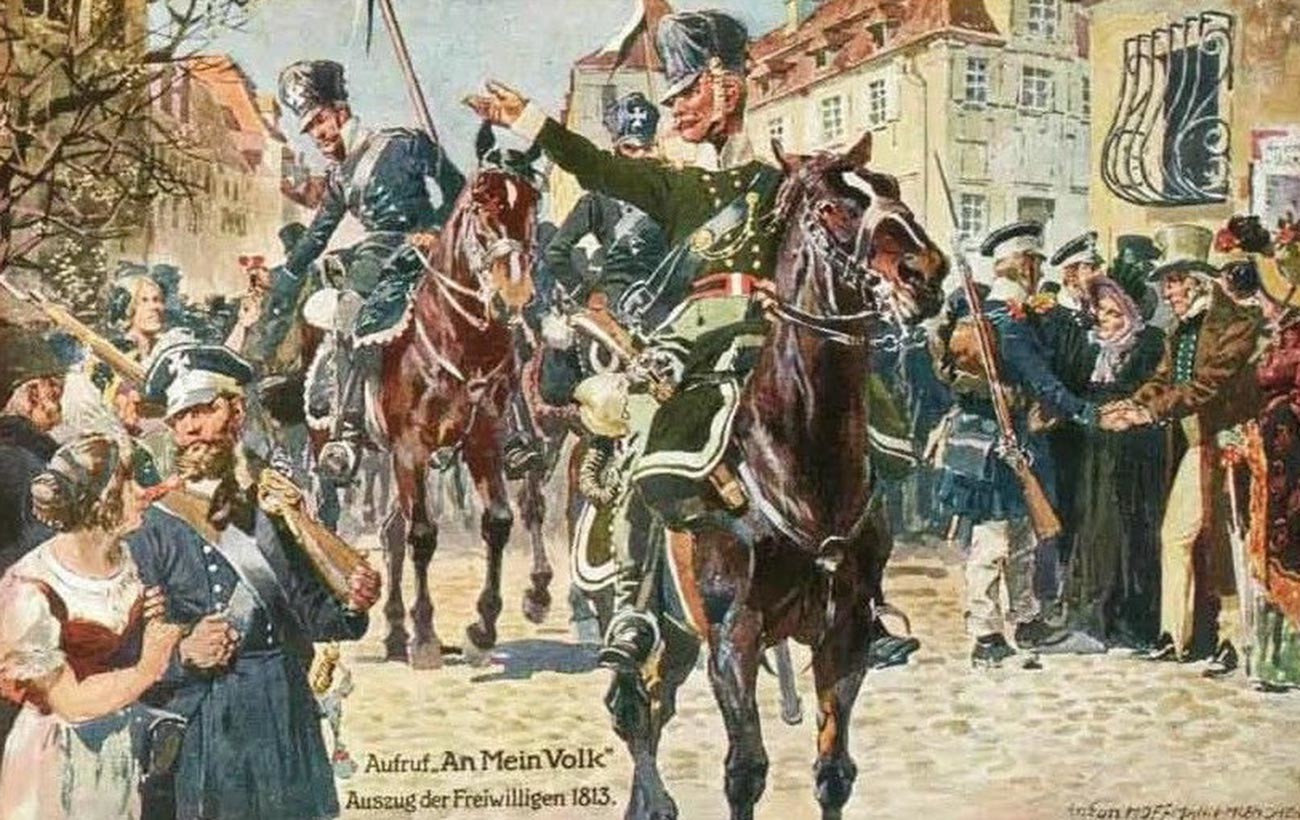

But when in January 1813 Russian troops showed up on the border of East Prussia, King Frederick Wilhelm III realized that the time had come to switch sides. His troops immediately joined the advancing Russian army, expelling the vestiges of the Grande Armée from Prussian soil.

During February of that year, most of the kingdom was liberated. But the enemy still held a number of large cities, including Berlin. The attack on the Prussian capital was led by the troops of Generals Nikolai Repnin-Volkonsky and Alexander Chernyshev. The latter, a relative of Zakhar Chernyshev, continued the family tradition of capturing this German city.

On Feb. 20, an advance party of several hundred Cossacks suddenly burst into Berlin. “It began with the Cossacks storming the Brandenburg Gate, scattering and overwhelming the guards. Then, with outrageous audacity, individually and in small groups, they tore from one end of the city to the other,” recalled a local eyewitness. However, they encountered strong resistance and had to retreat until the main force arrived.

Since the French sorely lacked cavalry, they could not prevent the flying Cossack detachments from attacking their rear and cutting off their communication lines. After the Russian troops had managed to throw a makeshift bridge over the River Oder, the commander of the garrison, Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, decided to leave Berlin.

Russian troops entered the city on March 4 practically breathing down the necks of the retreating enemy, and were warmly received by the locals. General Peter Wittgenstein reported that “a hundred thousand lips exclaimed incessantly: 'Long live Alexander, our deliverer!' The face of each and every one of them expressed the most vivid joy and affection. No artist’s brush could do justice to this delightful picture...”

On April 25, 1945, Soviet troops completed their encirclement of Berlin, and the next day began a decisive assault on the "lair of the beast." Around 400,000 Red Army soldiers took part in the fighting in the city streets, which were defended by up to 200,000 Wehrmacht, SS and Volkssturm militia troops.

The Germans did everything possible to turn their capital into an impregnable fortress. Each street became a line of defense, stuffed with barricades, dugouts, trenches and machine-gun nests. In addition, the enemy used the Berlin subway to conceal and quickly transfer troops. Soldiers also headed there to hide from artillery shelling and air strikes.

The closer the Soviets got to the city center, the fiercer the resistance became. “We ran into problems on entering the central districts where there were large houses with basements," recalled Junior Sergeant Pavel Vinnik: "From there, the Germans would strafe the entire street with gunfire. Not even a tank could enter!"

On April 30, the bloody battle for the Reichstag began. "In this vast building, the fighting became very localized," wrote Major General Vasily Shatilov in his memoirs: “Disjointed groups, struggling to navigate the labyrinth of corridors and halls, began to make their way to the second floor. The initiative shown by these groups and each individual soldier was decisive." Although the Soviet flag was hoisted over the Reichstag on May 1, the gunfire continued for another day.

After Hitler's suicide on April 30, General Hans Krebs, chief of staff of the German High Command, paid a visit to his Soviet counterpart proposing to conclude a truce. He was informed that the USSR would accept nothing less than unconditional surrender. After the new German leadership refused to take this step, the fighting resumed with renewed vigor.

The resistance of the defenders of the city did not last long, however, and on May 2 the Berlin garrison capitulated. The Battle of Berlin had been won at the cost of more than 75,000 Soviet soldiers' lives.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox