A Soviet family's housewarming.

Boris Kavashkin/SputnikProviding workers with a home of their own was one of the pillars of state policy in the Soviet Union. Before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, more than 80 percent of the country's population lived in villages. Just 10 years later, during a period of rapid industrialization, there was a massive influx of people to the cities, and all of them needed somewhere to live. At first, the problem was addressed by what was called uplotneniye (“compression” in Russian), a policy whereby members of the proletariat were allocated rooms in the large apartments of more affluent people free of charge along with promises that new housing would be built soon. The Soviet leadership also experimented with setting up communal housing and social communes, but really large-scale construction of new residential buildings only began in the 1960s with the introduction of inexpensive panel buildings known as Khrushchevkas and Brezhnevkas.

New settlers in the city of Naberezhny Chelny.

Ye. Logvinov/TASSThe most common way of getting an apartment was to join a waiting list to improve one's housing conditions. To qualify, an applicant had to be living in housing with less than nine square meters per person. Usually, young professionals could get on a waiting list when they had a baby. On average, the waiting time to receive an apartment from the state in the USSR was around six to seven years.

The easiest way was to get a job with an enterprise or organization that built housing for its employees. Then the waiting time could be just a couple of years. Public sector employees (teachers, doctors) could join a waiting list compiled by the local administration, but the waiting time on these could be more than 10 years. What’s more, applicants had no say over what type of apartment they would be given or where it would be located.

Moscow district of Troparyovo.

Anatoly Sergeyev-Vasilyev/Sputnik“After graduation, my parents, as young professionals, immediately received a room in a hall of residence, and when I was born, a one-room apartment not far from work,” writes Pyotr from the Krasnodar Territory. “When my sister was born, we were given a two-room apartment. Thus, just five years after graduation, the young doctors lived in an excellent two-room apartment."

Apartments were not given to people as their own private property, but rather were rented out for life in what was known as social rent. Tenants could register other people in their apartment, and they could swap their apartment with others (which, although not officially the case, sometimes involved additional cash payments). However, they could not sell, gift or bequeath their apartment to others.

“I received an apartment in 1979, a year after graduating from university when I was assigned a job in another city. Under the law, young professionals were entitled to an apartment within three years of employment,” recalls Galina from Kursk. “Having arrived in Dzhezkazgan (a regional center in Kazakhstan), I was given a place in a hall of residence and a year later, a one-room apartment. Having stayed in the job for the mandatory three years, I then returned to Kursk through an apartment swap."

Tyumen region, new settlers.

Andrey Solomonov/SputnikIf a tenant died, the apartment was re-registered in the name of another family member. If a tenant had no family, the apartment was returned to the state.

In July 1991, it became possible to privatize state apartments, and this process is still under way. The majority of people in Russian still live in privatized Soviet apartments.

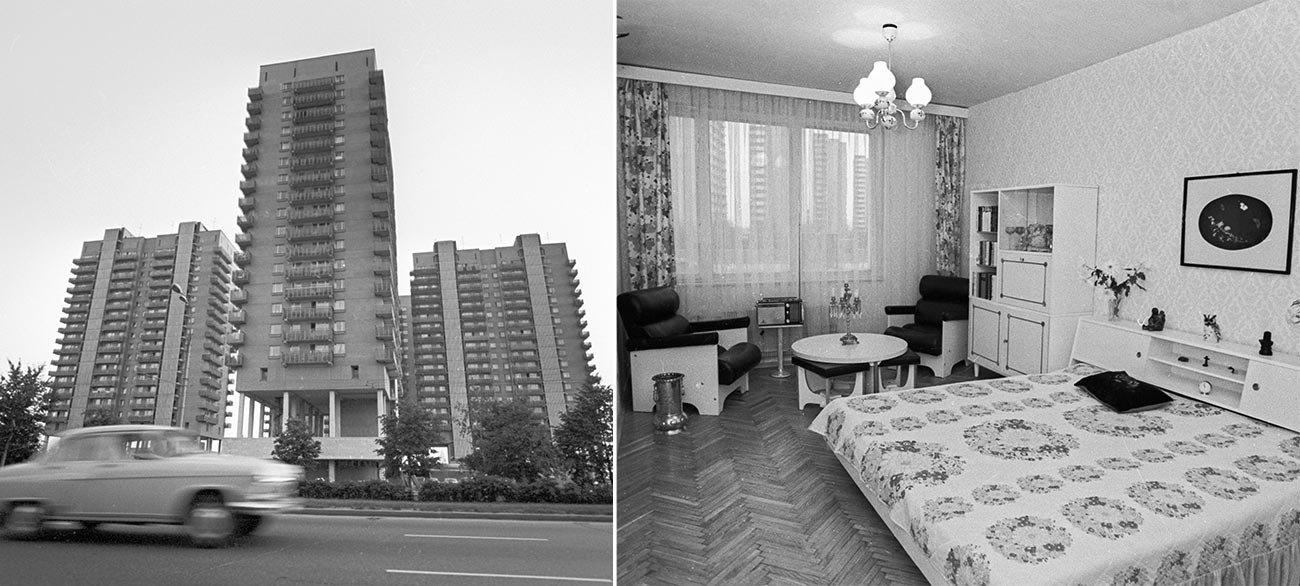

Left: A housing cooperative in Moscow. Right: An apartment in a condominium in Moscow.

Boris Kavashkin, Boris Babanov/SputnikThe Soviet Union did not have a housing market per se, but housing cooperatives began to appear in the late 1950s, and these essentially allowed members to buy an apartment in installments. Prices varied from region to region, but not significantly. In the 1970s-1980s, a one-room apartment cost 5,500-6,000 rubles (around the same as a new Volga car), while a three-room apartment cost about 10,000 rubles. The average salary in the USSR at the time was 150-200 rubles. Thus not many families could afford a condominium apartment, and housing cooperatives accounted for not more than 10 percent of housing in the USSR.

“My parents joined a condominium in Balashikha in the mid-1980s,” recalls Pavel from the Moscow Region. “The down payment was quite high, 3,000-4,000 rubles. They borrowed it from relatives. Monthly contributions were about 50 rubles, which was not too much as they had a monthly salary of 150-200 rubles each. In the end, they got a 60-65 sq. m. three-room apartment for the three of us."

A housewarming party at the Atom residential complex for youth in Moscow.

Sergei Samokhin/SputnikSome people invested money in an apartment, while others invested their labor. Several Soviet cities participated in a project whereby young specialists temporarily left their permanent jobs and went to work on a construction site to build housing for themselves. At the same time, the time they spent on the construction site counted towards their length of service at their main place of work. This practice first emerged in the 1960s in Korolyov, a town outside Moscow with a large scientific industry. The town hired the best graduates from all over the country to work at its space research institutes but did not have enough housing to accommodate them. Then, with the approval of the Komsomol young communist league, it was decided to build new apartment blocks with the help of their future residents.

Joining a project like that was considered a privilege. It not only allowed participants to gain new housing, but also many of those developments were based on original designs and featured numerous social facilities that set them apart from the humdrum residential neighborhoods built elsewhere. At first, these projects were funded by employers and then later by the State Planning Committee. Many of those residential developments were actually completed after the collapse of the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox