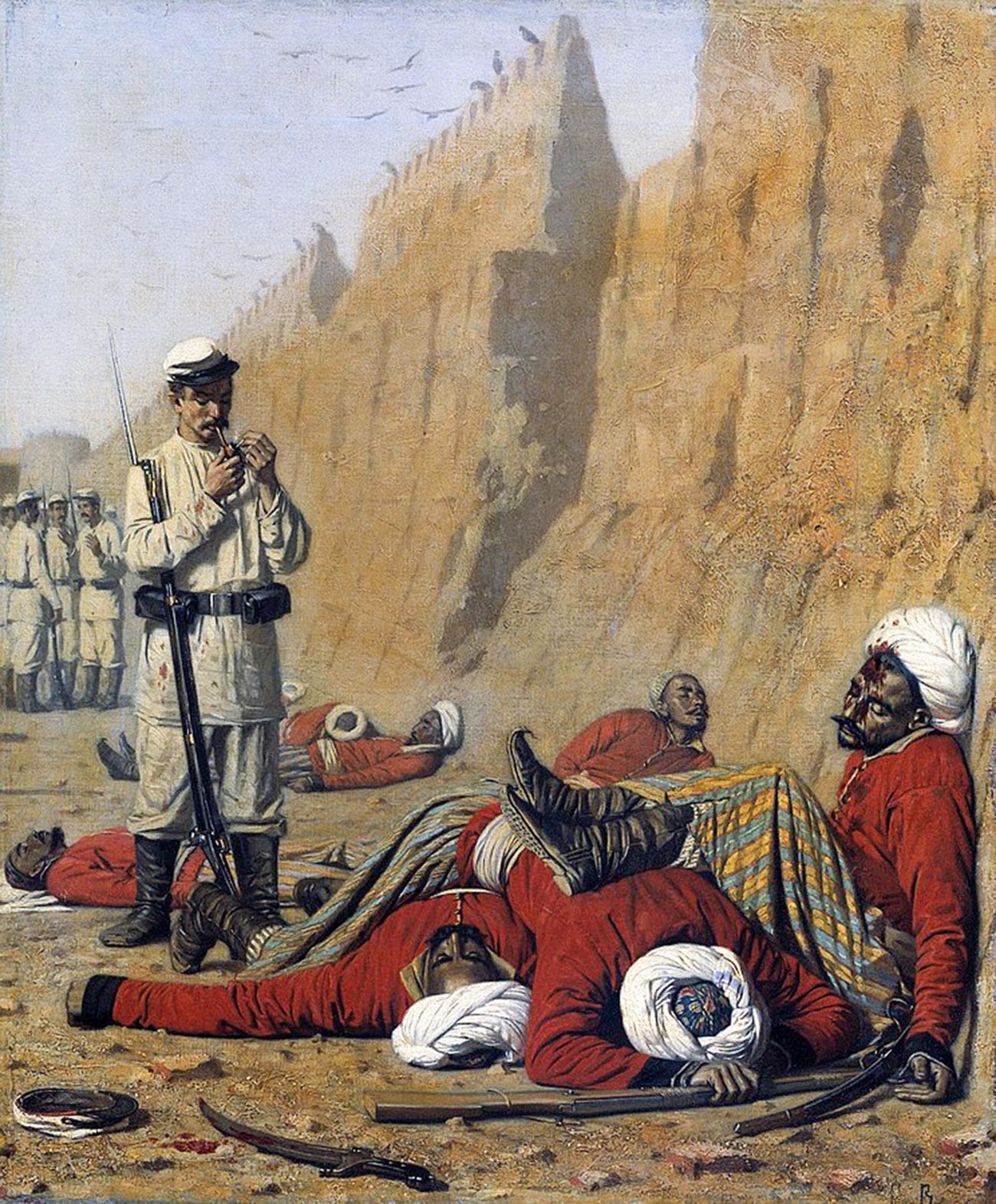

"By the Fortress Wall. 'Let Them Come in'".

Vasily Vereshchagin/The State Tretyakov GalleryCentral Asia, stretching from the Kazakh Steppe to Afghanistan and from the Caspian Sea to the Chinese border, was the last major territorial acquisition of the Russian Empire before it collapsed in 1917.

For a long time, Russia didn’t dare interfere in the affairs of the Central Asian region. The territory of present-day Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan was a veritable seething cauldron. Dozens of tribes and small states waged endless brutal wars and bloody feuds with one another there.

Cossacks fight Kyrgyz.

Alexander OrlovskyThe khanates of Kokand and Khiva (Khwarazm), as well as the Emirate of Bukhara (before 1785 - Khanate of Bukhara), were the largest state entities in Central Asia. Even in the 18th century, a medieval feudal order dominated there and slavery flourished extensively.

Khanate of Kokand.

Library of CongressIn 1714, Tsar Peter I sent a military expedition to Khiva to test the strength of his Central Asian neighbors. Better prepared and equipped, the 6,000-strong detachment of Prince Alexander Bekovich-Cherkassky easily scattered the 24,000-strong army of Shir Ghazi Khan. Then, the ruler of Khiva resorted to a trick. He proposed a truce, during which he launched a surprise attack and slaughtered or captured the Russian soldiers. He sent the head of the prince himself as a present to the Khan of Bukhara.

Alexander Bekovich-Cherkassky.

Fyodor VasilyevDuring the 18th century, Russia was actively expanding into the Kazakh Steppe and came close to the borders of the Central Asian states. The Kazakh clans of the so-called Junior and Middle Zhuzes (hordes), who sought protection from the Russians against the devastating raids of the neighboring Dzungars, voluntarily submitted to the Tsar’s rule. In turn, the Senior Zhuz remained under the political control of Kokand.

Muhammad Khudayar Khan, a Khan of Kokand.

Public DomainThe relatively peaceful coexistence of Russia and the Central Asian states came to an end towards the middle of the 19th century. The reason for this was the arrival of a dangerous new player in the region - Great Britain. The British, having established a foothold in Hindustan, were actively advancing north, trying to spread their influence to Afghanistan, Bukhara, Kokand and Khiva. When British diplomats and War Office secret agents turned up in Central Asian cities, Russia decided to get ready to make a preemptive strike. Central Asia became an arena of confrontation between the two empires, widely known as the ‘Great Game’.

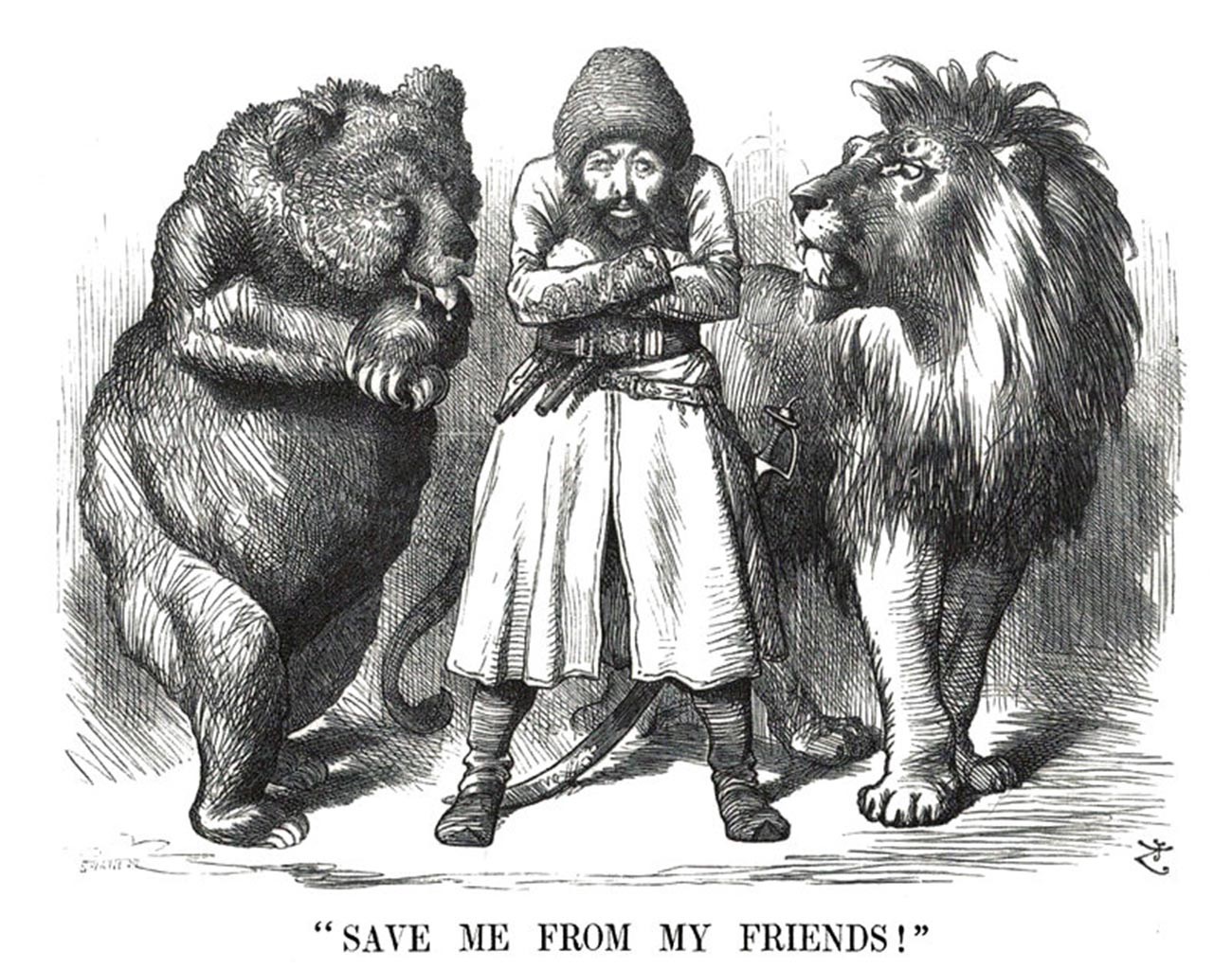

Caricature from the times of the “Great Game”.

Public DomainRussian expansion into the Central Asian region also had economic causes. The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 led to a sharp reduction in the supply of cotton to Russia, something that hit the empire’s textile industry hard. In the circumstances, an alternative and stable source of this important raw material had to be found urgently and Kokand and Bukhara could play this role.

"By the Fortress Wall. 'Let Them Come in'".

Vasily Vereshchagin/The State Tretyakov GalleryThe Central Asian states had practically no prospect of resisting Russia’s armies. The combat training of their soldiers left much to be desired, while no more than a quarter of their men were equipped with firearms. “No regular army exists in Kokand,” wrote Orientalist and historian Vladimir Velyaminov-Zernov in the 1850s. “The Kokand army does have artillery, but it is so bad that it can scarcely be called by that name.”

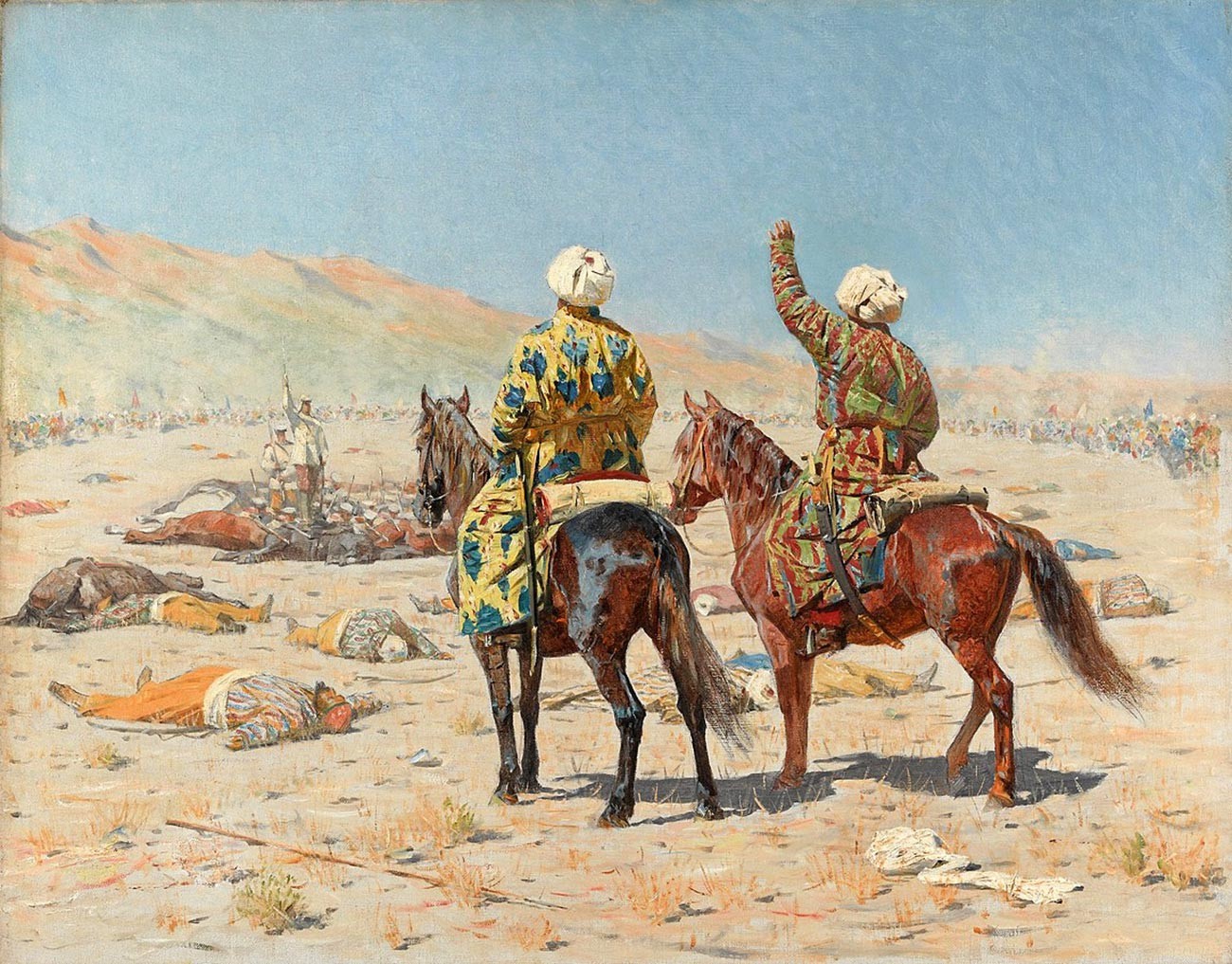

"Parliamentarians".

Vasily Vereshchagin/The State Tretyakov GalleryAt times, the huge numerical superiority of the Khivan, Bukharan and Kokand forces was of no account when they were confronted by well-trained Russian troops. On June 29, 1865, a small (1,300-man) detachment led by Gen. Mikhail Chernyayev seized one of the biggest and wealthiest cities in the Khanate of Kokand - Tashkent - which was being defended by a 30,000-strong enemy garrison. Two years later, the city became the administrative center of the Turkestan governor-generalship that was established in Central Asia.

"After failure".

Vasily Vereshchagin/The State Russian Museum“These handfuls of our soldiers, surrounded and isolated by a swarm of Bukharan horsemen, having advanced all the way to a position regarded as impregnable and occupied by a 10 times stronger enemy, presented a strange sight. But that is the meaning of strength of spirit and a courage to which nothing is impossible,” is how officer Aleksey Kuropatkin, the future Russian Imperial Minister of War, described the taking of the city of Samarkand in the Emirate of Bukhara on May 27, 1868, in his book of memoirs, The Conquest of Turkmenia.

“Surprise Attack”.

Vasily Vereshchagin/The State Tretyakov GalleryIn the Battle of the Zerabulak Heights on June 14, 1868, the 30,000-strong army of Emir Muzaffar was crushed by a 2,000-man detachment led by Gen. Konstantin Kaufman, something that ultimately brought about the defeat of the Emirate of Bukhara. In 1873, a similar fate befell the Khanate of Khiva and, three years later, the Khanate of Kokand.

Konstantin Kaufman.

K. Brozh; L. SeryakovOne of the most difficult operations for Russian troops during the conquest of Central Asia was the subjugation of the Teke tribes who lived on the territory of today’s Turkmenistan. In the siege and storming of the fort at Geok Tepe in January 1881 alone, they lost more than 1,000 men. Meanwhile, in the most bitter fighting against the Bukharans and Khivans, casualties had been numbered in mere dozens.

Oil painting depicting a Russian assault on the fortress of Geok Tepe during the siege of 1880-81.

Nicholas KarazinWith the voluntary accession of the Merv tribes to the Russian Empire in 1884 and the arrival of Russian troops at the borders of Afghanistan, which was under British protectorship, the conquest of Central Asia as a whole was complete. With the arrival of the new authorities, slavery was abolished and the centuries-old feuding of the local population was brought to an end. Far from all the territories were incorporated in the Empire, however. Although greatly reduced in size, the Emirate of Bukhara and Khanate of Khiva formally retained their independence while accepting Russian protectorship. This allowed the country’s leadership to exercise effective control over these regions, without having to expend significant resources. “My best district chief is the Emir of Bukhara,” said Governor-General of Turkestan Konstantin Kaufman. The two states’ independence was only finally extinguished by the Bolsheviks in 1920.

Receiving of cotton in Kokand.

Wilhelm GarteveldGreat Britain, whose arrival in the Central Asian region was what had largely provoked Russian expansion, had to look on helplessly at the triumphs of its geopolitical opponent. After finding itself on the receiving end of the large-scale Sepoy Mutiny in India in 1857-59, London had neither the strength nor the resources to enter into open conflict with Russia and confined itself to issuing diplomatic protests.

Sepoy Mutiny.

GrangerAlthough Central Asia was lost to the British, they carefully safeguarded the routes to Afghanistan and India from the Russians. When a border conflict flared between Russian and Afghan troops on the River Kushka in 1885, Britain was one step away from declaring war on Russia. In subsequent years, the sides sat down at the negotiating table on numerous occasions, in order to mark out spheres of influence in the region. The ‘Great Game’ between the two empires only came to an end in 1907 with the signing of the Anglo-Russian Convention, which finalized the formation of a military-political bloc consisting of Russia, Great Britain and France, known as the ‘Triple Entente’.

Battle of Kushka.

Franz RoubaudIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox