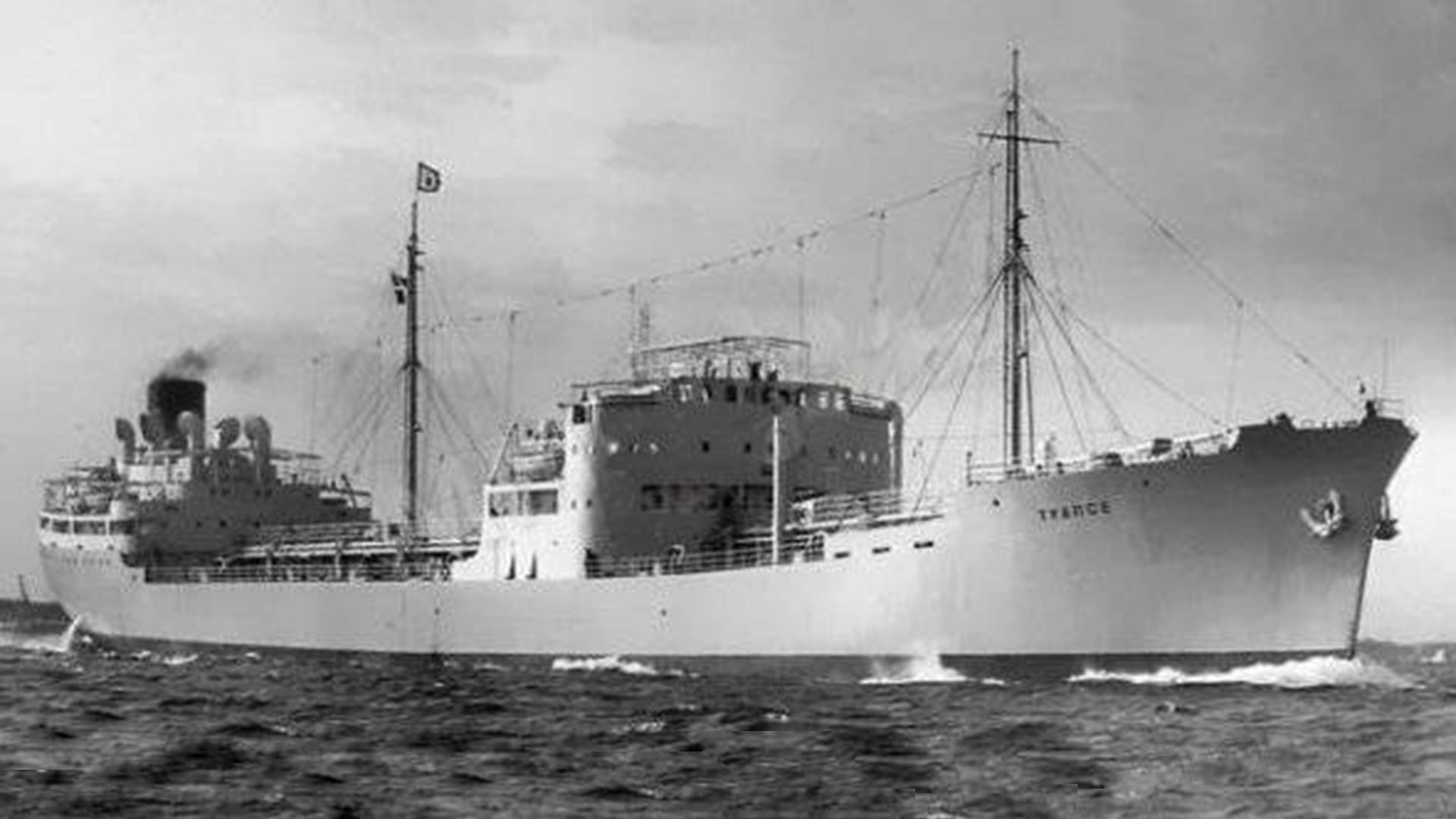

The Soviet tanker ‘Tuapse’.

korabley.netOn June 23, 1954, an event occurred that sent reverberations through the USSR. The Soviet tanker ‘Tuapse’ had been captured in international waters in the South China Sea. And it was done not by pirates of some kind, but by the Republic of China Navy itself. SO, how did little Taiwan come to decide on open conflict with one of the leading world powers?

The Soviet Union and the Republic of China were not always enemies. In the second half of the 1930s, Moscow actively supported Chiang Kai-shek’s ruling Kuomintang party, which was opposing Japanese aggression, by sending it financial support, weapons and military specialists.

Later, however, the paths of the two countries fundamentally diverged. The USSR sided with Mao Zedong’s ideologically kindred communists and yesterday’s friends turned into foes.

Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, 1950.

Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesIn 1949, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) drove Chiang Kai-shek’s followers from the mainland to the island of Taiwan, but the latter didn’t resign themselves to defeat. Enlisting the support of its American allies, the Kuomintang tried to impose a naval blockade on the People’s Republic of China and detained foreign cargo ships on their way to the communists.

After their cargoes were confiscated, the ships were usually allowed to proceed on their way.

Soviet ships were the only ones Chiang Kai-shek didn’t dare touch. This fear, however, disappeared in the spring of 1953, following the death of “all-powerful leader” Stalin and the ensuing power struggle in the USSR.

The Soviet tanker ‘Tuapse’, which had left Odessa in May 1954, was on its way to Shanghai carrying ten thousand tons of aviation fuel intended for the PLA Air Force. When it had almost reached its destination, it was intercepted by two Taiwanese destroyers.

Officer Cui Changling, who took part in the operation to capture the tanker, fled to mainland China some time later. “I couldn’t help wondering how come the Chiang Kai-shek command decided to demonstrate such audacity,” he said during questioning. “I soon received an exhaustive answer to this question from the captain. It happened when early in the morning of June 23 we saw the ‘Tuapse’ and proceeded towards it. At that moment, I was standing on the command bridge and saw through my binoculars in the distance the silhouettes of two more ships and immediately reported this to the captain. He said that the ships belonged to the U.S. Navy. The captain said they had met the ‘Tuapse’ in the Bashi Channel and were accompanying it to the pre-arranged capture site, reporting the coordinates of the Soviet vessel to the Kuomintang command.”

The Chinese ships fired several warning shots, ordering the tanker to stop. An armed assault party came on board and took control of the ship. The radio room only had time to send a single message home to say that the ship had been seized.

A still from the Soviet movie 'E.A. — Extraordinary Accident', based on real events of the capture of the Soviet tanker 'Tuapse'.

Viktor Ivchenko/Gorky Film Studio/Dovzhenko Film Studio, 1958The ‘Tuapse’ was brought to the Taiwanese port of Gaoxiong. There, according to Cui Changling, several American military advisers dressed as civilians came on board. They confiscated all the paperwork and carefully examined the tanker.

The Soviet Union immediately reacted to the incident. Moscow did not recognize the Taiwanese government and its note of protest was sent straight to the U.S. “It is perfectly apparent that the seizure of the Soviet tanker by a naval vessel in waters controlled by the U.S. Navy could only have been carried out by U.S. naval forces. In connection with this attack on a Soviet merchant vessel in the open sea, the Soviet government expects the U.S. government to take steps to ensure the immediate return of the ship, its cargo and its crew,” the note said. The text of the note was published in the Pravda newspaper on June 25, 1954.

Since Chiang Kai-shek continued to hold the vessel and its crew, the Soviet Union and a number of Socialist Bloc countries stepped up their diplomatic pressure, including at the U.N. Even Australia and New Zealand, which were friendly to the Americans, privately expressed their concern that the incident could give the USSR a pretext to step up naval operations in the western part of the Pacific Ocean.

The American and Taiwanese special services, however, were in no hurry to meet Moscow’s demands. They had their own plans for the Soviet sailors.

The 49 crew were divided into groups of 10-15 each and immediately isolated from one another. Every day, they were subjected to psychological brainwashing in an attempt to get them to ask for political asylum in the U.S. The aim was to damage the Soviet Union’s image and show that people were allegedly fleeing it at any opportunity.

The sailors were given the status of prisoners of war, kept on starvation rations and subjected to beatings, or, conversely, attempts were made to bribe them with the promise of a comfortable and prosperous life in the West. At one point, they were even told that World War III was under way and, if they did not change sides, they would simply be shot.

Only a year later did the Soviet Union manage to, with the mediation of the French, secure the release of 29 crew members, including the tanker’s captain, Vitaly Kalinin. For all the pressure they had been subjected to, they categorically refused to sign anything.

A still from the Soviet movie 'E.A. — Extraordinary Accident', based on real events of the capture of the Soviet tanker 'Tuapse'.

SputnikThe released men received a hero’s welcome when they reached home. They were paid compensation for having been prisoners, presented with awards and given good jobs on ships. “There were times when we lost all hope of returning. We were mainly afraid of dying of starvation: Everyone was so emaciated that they looked like walking skeletons,” recalled Yury Boriskin.

A more melancholy fate awaited the 20 people who did sign the asylum applications. Nine of them were taken to the U.S., where two even broadcast criticism of the Soviet system on the radio. Five decided to return home soon afterwards and, in April 1956, they fled to the Soviet embassy. At home, their welcome was a muted one; they were kept under supervision and no longer allowed to sail international routes. Nikolai Vaganov, one of those who had made radio broadcasts, was arrested (not straight away, but only in 1963), convicted of treason and given a sentence of 10 years.

The four who remained in the U.S. were sentenced to death in the Soviet Union in absentia. One of them - Mikhail Ivankov-Nikolov - went mad soon afterwards and the Americans themselves handed him over to the Soviet side in 1959. At home, he was not shot, but placed in a psychiatric hospital, where he spent 20 years.

Another four sailors who had signed asylum applications were able to leave Taiwan for Latin America in 1957 and, from there, to return to the USSR. A big press conference was initially organized for them, but they were subsequently sentenced to terms of up to 15 years for treason.

Of the sailors remaining on the island, two died and another committed suicide. Four withdrew their signed applications for asylum in the U.S. and were put in a local prison. After release, they lived in a settlement by the sea under the supervision of the Taiwanese police. It was only 34 years later, in 1988, that the Soviet consul in Singapore managed to get them repatriated.

The tanker ‘Tuapse’ was never to see the shores of home again. After serving in the Republic of China Navy under the new name of ‘Kuaiji’, it was sent for permanent moorage in the port of Kaohsiung, where it is to this day.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox