Emperor Nicholas II of Russia and his wife, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, cosplaying the 17th-century Russian ruling couple during the celebrations of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty, 1913.

Public domain; KlimbimAlthough there are still doubts and uncertainties about the exact details surrounding the summoning of the Varangians, historians agree that whoever Rurik, the Varangian prince was, he wasn’t Russian by birth.

Rurik, from a 17th-century Russian manuscript

Public domainWe can safely assume that the first princes of the Russian lands were Nordic. They even bore Scandinavian names – Igor, Oleg, Olga. However, with the arrival of the 10th century, they were assimilated into and became one with the Russian population.

Vladimir the Great, the Kievan prince who baptized Russia, was a born Rurikid, Rurik’s great-grandson. He sought to establish dynastical ties with foreign countries. In pursuit of this mission, he arranged marriages of some of his daughters to foreign princes and kings – although we can’t tell for certain how many exactly, due to insufficient historical sources.

His daughter Premislava (d. 1015), for instance, became the spouse of Hungarian Prince Ladislas the Bald (997-1030), while Maria Dobroniega (1012-1087) was the wife of Casimir I the Restorer, Duke of Poland (1016-1058). However, none of Vladimir’s daughters or their offspring returned to Russian lands.

The Rurikids continued to rule Russia until the early 17th century, when, after the Time of Troubles, the Romanov dynasty took the Russian throne.

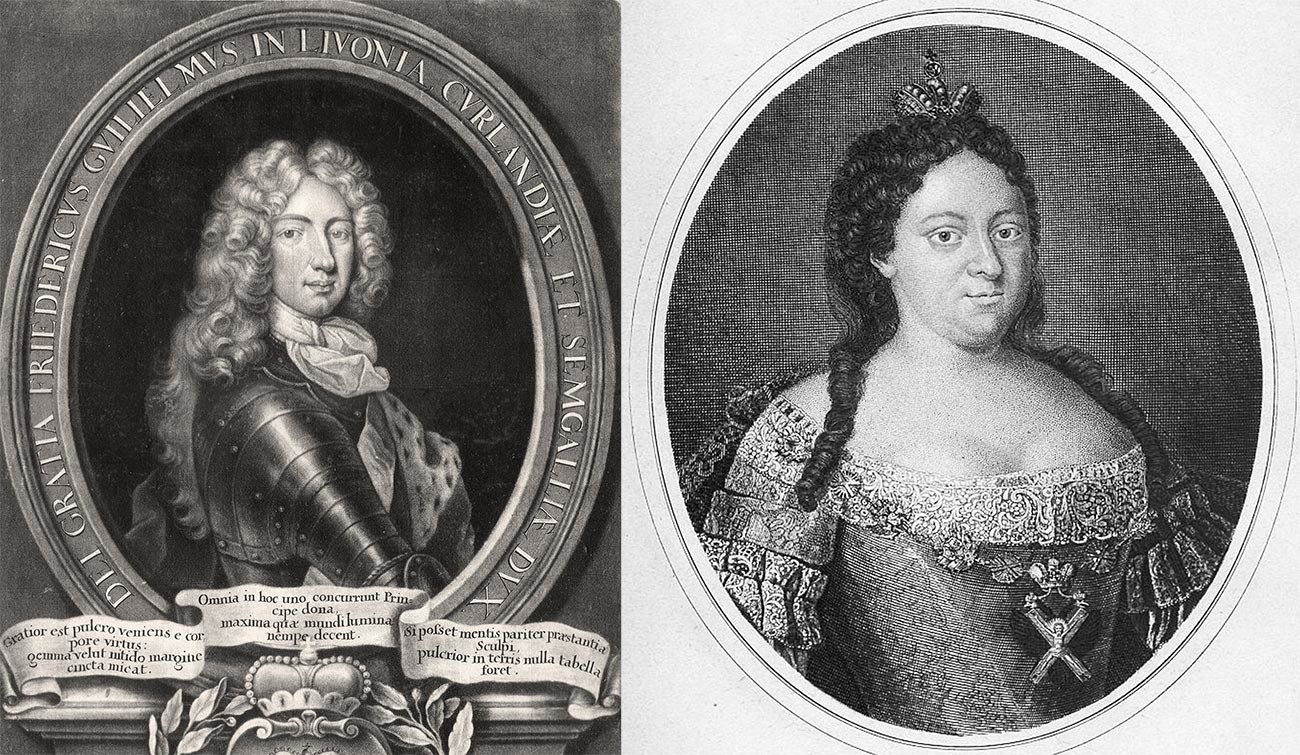

Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Courland, and Anna Ioannovna

K. Weygel; Ivan SokolovTsar Alexey Mikhailovich (1629-1676), Peter the Great’s father, was very rigorous about issues of tradition when it concerned dynastic marriages. He didn’t approve of his daughters marrying foreign princes, most likely because he didn’t want a foreign dynasty to have rights to the Russian throne.

Unlike Alexey Mikhailovich, his son Peter used his daughters and nieces as pieces in a great European dynastic game. He managed to arrange the marriage of his niece, Anna Ioannovna (1693-1740), to Frederick William, Duke of Courland (1692-1711), who unfortunately died shortly after the marriage, perhaps because of the heavy drinking at the Russian court. Anna and Frederick William had no children.

Meanwhile, the daughter of Peter and his second wife Catherine (1684-1727), Anna (1708-1728), who was born even before Peter married Catherine, became the wife of Charles Frederick, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp (1700-1739). Anna moved to Kiel, the capital of the German land of Schleswig-Holstein. And although she died young, just three months before her death, she gave birth to Charles Peter Ulrich of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp (1728-1762), who would become the Russian Emperor under the name of Peter III.

Russian Emperor Peter III

Lucas Conrad PfandzeltElizabeth Petrovna (1709-1762), another of Peter’s and Catherine’s junior daughters, was the last Russian ruler to have at least half Russian blood coursing through her veins (Catherine was Livonian by birth). Peter III, who became her successor, was overthrown by his wife, Catherine (1729-1796), born Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst.

The only son of Peter III and Catherine II, Paul I of Russia (1754-1801), married twice, both times to German princesses. His first wife, Princess Wilhelmina Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt (1755-1776), died in childbirth, together with her stillborn son, while his second, Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg (1759-1828), became Maria Feodorovna after adopting Russian Orthodox faith.

Maria Fyodorovna and Paul I of Russia

Vladimir Borovikovsky; Stepan ShchukinAll of Paul’s and Maria’s children, including Alexander (1777-1825) and Nicholas (1796-1855) – who would become Russian Emperors consequently, were fully German by birth, and all of their offspring were, too, because in the 19th century, Russian Emperors, remarkably, didn’t marry any Russian princesses – there were simply no matches for them in a dynastic sense, and the Romanovs of the 19th century strictly adhered to the rules of succession to the throne, established in Russia. These rules stated that heirs to the Russian throne must only marry women who were close or equal to them in royal status – and in Russia, there were no other dynasties that could match the Romanovs. They simply had no choice but to marry European princesses – preferably German, because of the long-lasting ties that started with Peter’s daughter Anna marrying the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp. Eventually, that led to the Romanovs and the House of Windsor (formerly, German House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha) becoming closely related.

Nicholas II in 1913, wearing a traditional costume of Russian Grand Princes of the 17th century

Public domainBy the end of the 19th century, the Russian Emperors barely knew Russian: Alexander III (1845-1894) spoke Russian with a thick German accent, while his son Nicholas II (1868-1918), the last Russian Emperor, preferred to communicate in English even with his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna (1872-1918), born Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine.

Although, in 1913, Nicholas and Alexandra dressed themselves and all of the royal Russian court in traditional Russian clothes – modeled after the garments of the 17th century, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty – they were merely cosplaying Russians.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox