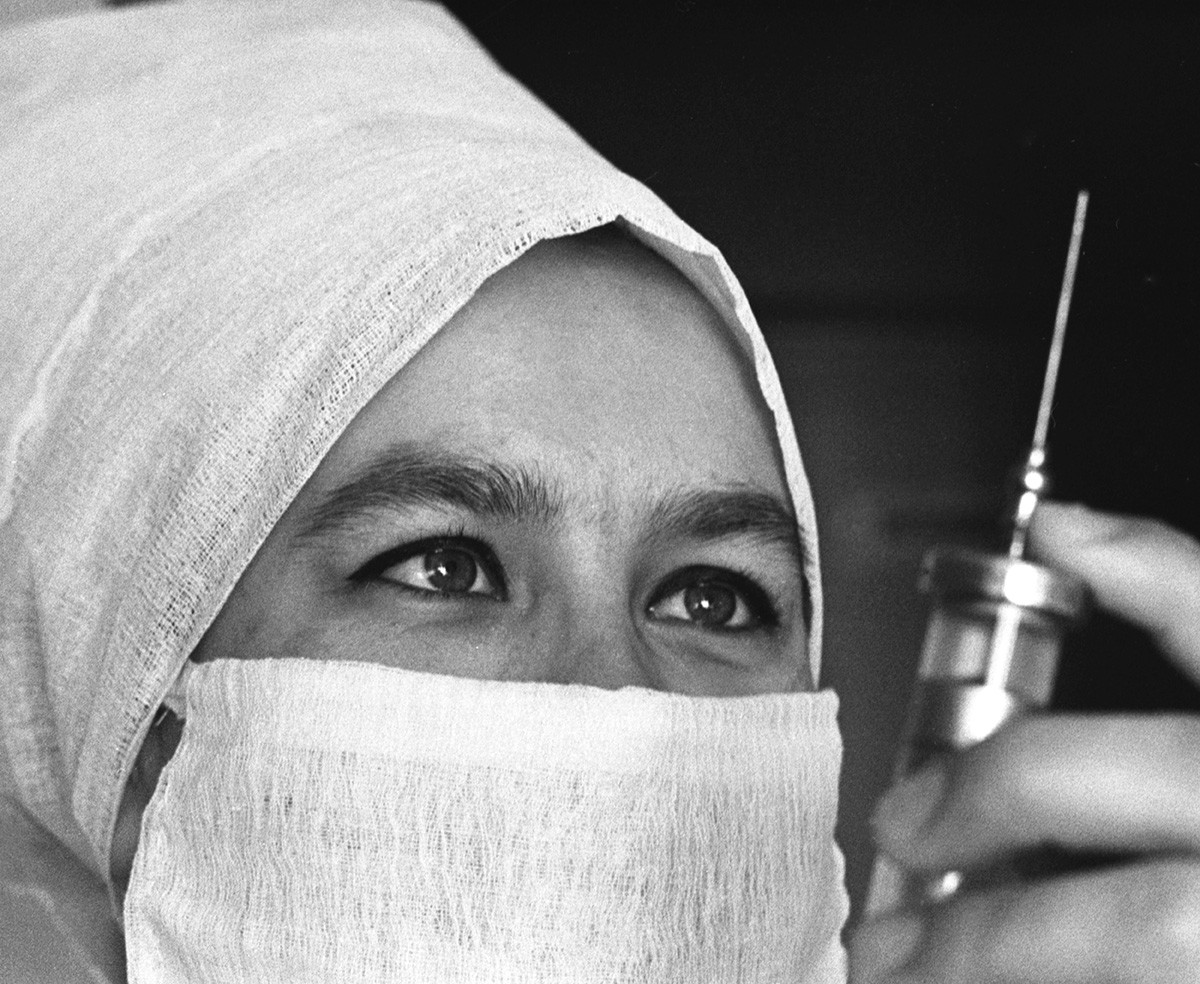

Vaccination against influenza, Leningrad, 1978.

V.Baranovsky/SputnikThe Soviet health care system was considered and is still considered by some, to be one of the best or even the best in the world. According to statistics and information provided by the Soviet authorities, the post-war USSR was highly effective in combating viral diseases and the healthcare system never faced anything that might be termed as an epidemiological crisis. Personal hygiene propaganda and pro-vaccination campaigns contributed to the nation’s health. However, judging by the living habits of the Soviet people, it is quite difficult to say with 100% certainty that the number of infectious cases was low.

The first challenge that comes to mind if we are talking about infectious diseases is the Russian flu, which was first recorded in 1977 and lasted till 1979. Despite the fact that this new strain was first identified in China, the virus was given the name ‘Russian’ (or simply ‘Red’), because the USSR was the first country to officially report on it.

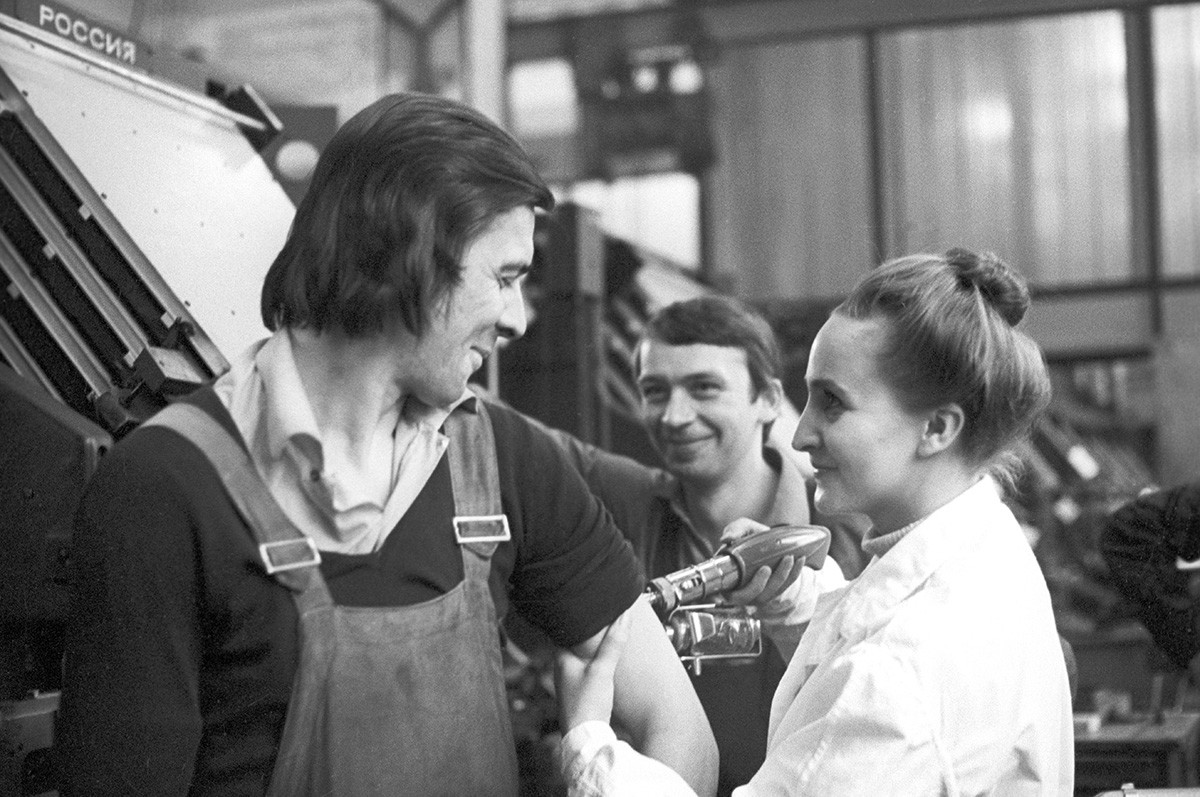

Vaccination against influenza at the factory in Leningrad, 1977.

V.Baranovsky/SputnikThe strain of the Russian influenza was 99% similar to H1N1 (the one which also caused the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 and the swine flu pandemic in 2009). This is the reason why it is considered that the great majority of patients were young people under 25 years old, whose organisms had never been exposed to H1N1, which circulated worldwide in the 1940s-1950s. However, concerning the number of infected people and the subsequent death toll, it is almost impossible to say anything with 100% certainty. Why? The problem was absolute secrecy. There is still no comprehensive data for this flu outbreak. That is why there are a lot of rumors about this influenza. There are those who say that the number of deaths from the disease in the Soviet Union exceeded 1 million people. Conspiracy theory supporters advanced further, claiming that the Russian flu was of artificial origin and aimed at killing the youth. But these are just theories. If we look at the fact that an estimated influenza mortality rate worldwide was around 5-6 in every 100,000 people, we can infer that the death toll was not that high.

The Summer of 1970 was marked by an outbreak of cholera in the south of the USSR. Astrakhan was actually the city which “took the brunt” of the virulent disease. Until the end of August, nearly 200,000 people were vaccinated, while thousands of local residents and travelers were placed under quarantine. Thanks to the timely measures, the outbreak began to wane by early September.

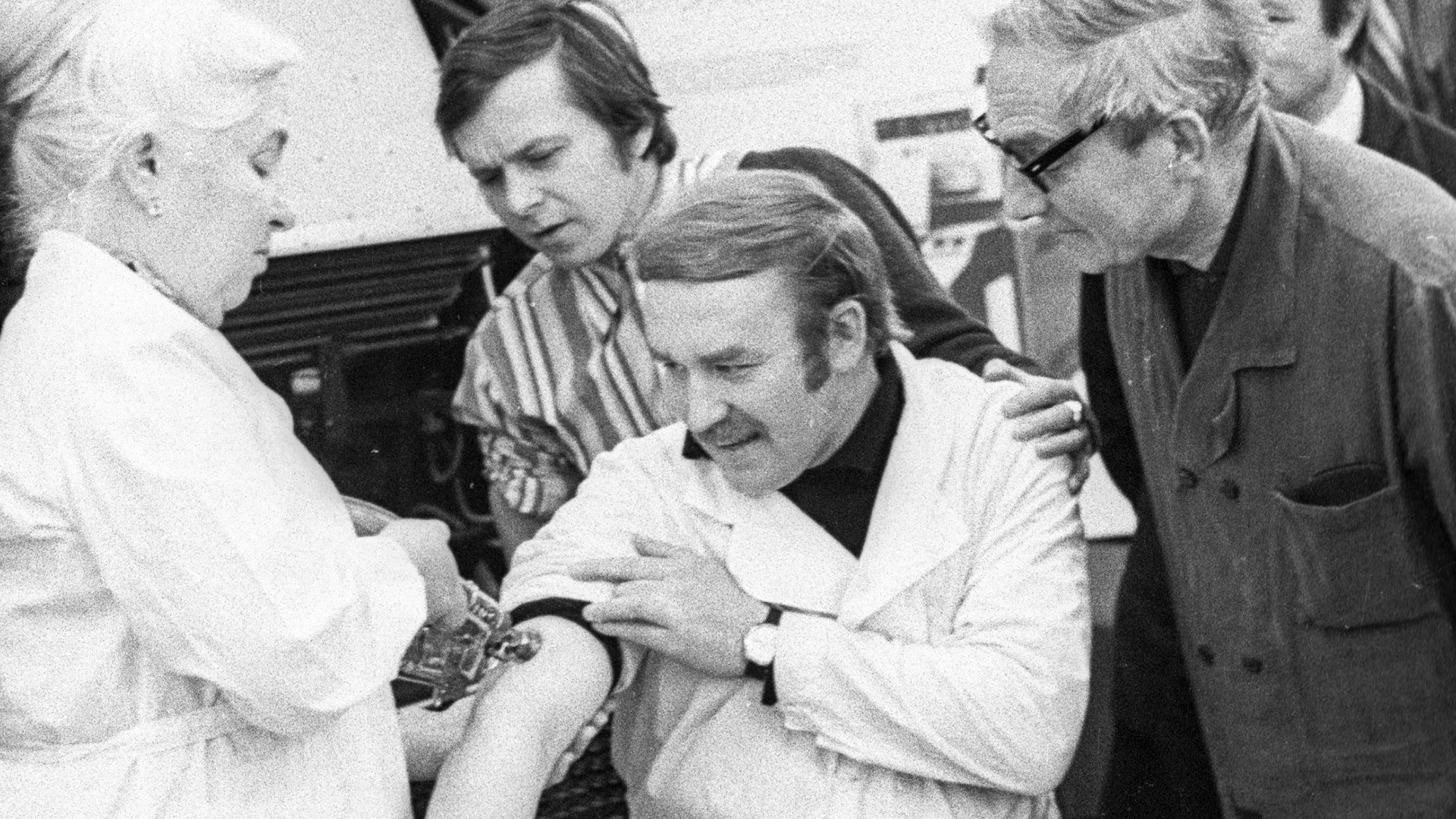

Fighting the cholera epidemic in Astrakhan. Sending patients from the city who are under the supervision of doctors. The photo was published in the Sovetsky Soyuz magazine in 1970.

May Nachinkin/SputnikTimely measures were the key to success. Moreover, we have to understand that the Soviet authorities didn’t do half-measures and resorted to forceful methods of containing the outbreaks. For example, in case of cholera, 3,000 soldiers were sent to Astrakhan to keep order and to monitor the compliance of quarantine. Troops were also sent to Crimea and Odessa.

Sending a cholera patient to an infectious diseases hospital in Astrakhan, 1970.

May Nachinkin/SputnikAnother crucial factor in the USSR’s success story was its mass immunization campaign. Those born in the post-war USSR were vaccinated against tuberculosis, diphtheria and poliomyelitis. Over time, vaccines against pertussis, tetanus (Lockjaw), measles and parotitis were added to the mandatory list (read our article for more information about the stories behind polio vaccines). As it came to virulent outbreaks, the vaccination campaigns accelerated (as in the case of cholera), thereby stopping the proliferation of diseases in the early stages.

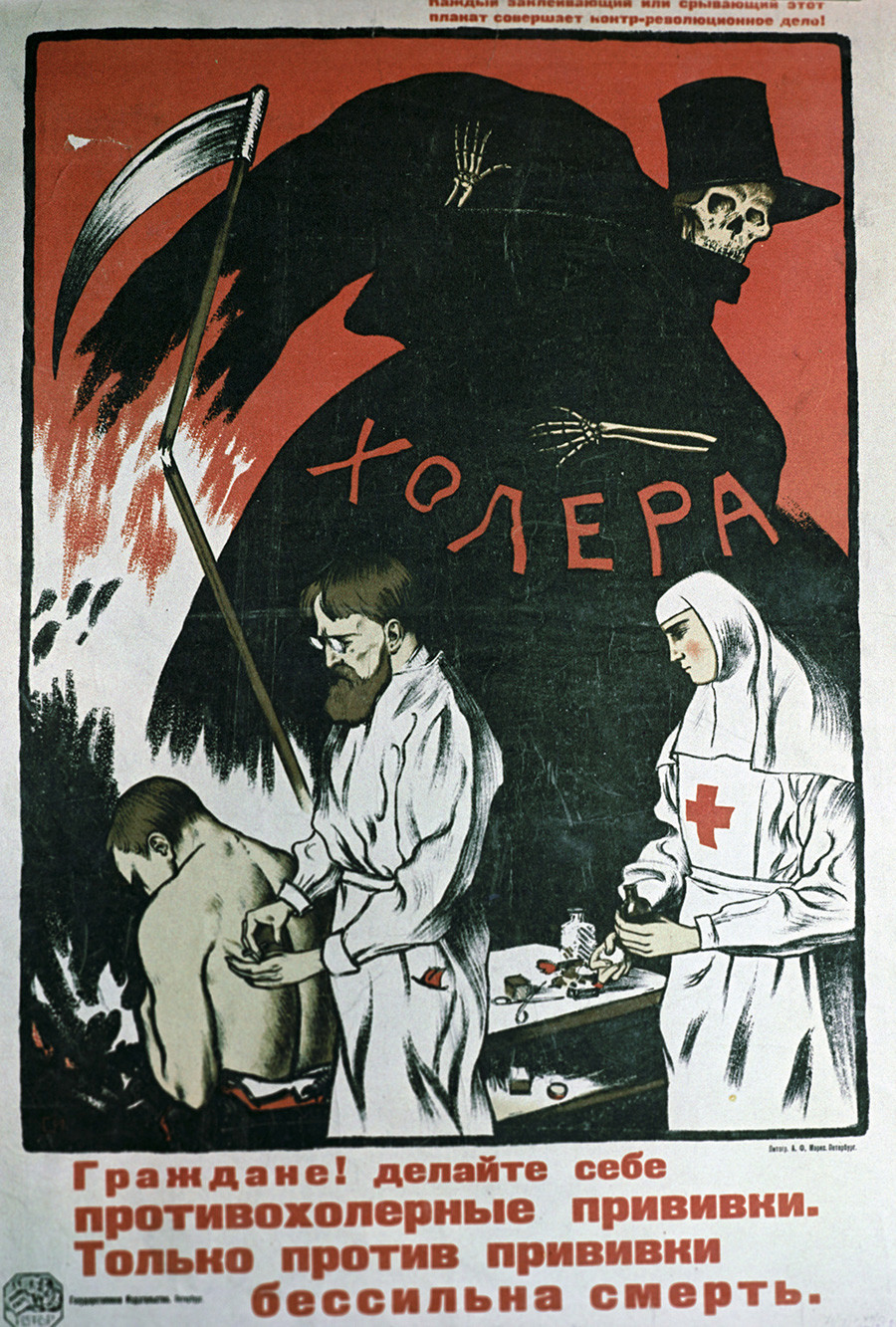

This immunization program was also accompanied by a huge pro-vaccination campaign and propaganda of personal hygiene.

"Make anti-cholera vaccinations"

Sverdlov/SputnikSlogans like, “Temper yourself if you want to be healthy” (condition yourself to the cold to become strong and healthy) or “Hurray for towels and sponges! Hurray for soapy foam!” entered into common parlance of every Soviet citizen and were transmitted from generation to generation.

Temper yourself if you want to be healthy”

Archive photoSoviet animation was an integral component of this campaign. For example, it is almost impossible to find a person born in the USSR who has never watched the ‘Moydodyr’ cartoon (it is still extremely popular these days).

The animated movie itself is based on the verses of renowned children’s poet Korney Chukovskiy and aims to encourage good hygiene practices.

A scene from the Soviet animation about hygiene.

Ivan Ivanov-Vano/Soyuzmultfilm, 1954Another example is a cult Soviet cartoon titled, ‘About a hippo who was afraid of vaccinations’. The story tells of a Hippo who was so scared of injections that he escaped from a hospital. However, he soon got sick and was delivered back on stretchers to hospital where he blushed with shame in front of a doctor. So, the idea of the cartoon is to let children (probably not only children) know that there is nothing scary about vaccination.

A scene from the Soviet animation about a hippo who was afraid of vaccination.

Leonid Amalrik/Soyuzmultfilm, 1966However, concerning hygiene and sanitary, not everything was so perfect. The first example is the soda pop machines, which were widely widespread across the Soviet Union. Who wouldn’t want a glass of cold soda on a hot summer day? But the thing is, these machines only offered no more than two (but usually one) drinking glasses. The average Western citizen would point to poor personal hygiene, however, the Soviet people didn’t think much about it.

These glasses could easily carry viruses and, for example, in the late 1970s, the Russian flu could have easily been transmitted via them. But there is no data about it in as much as the studies concerning a linkage between the soda pop machines and the spread of infections had never been published or publicly discussed.

Another issue that may shock a modern person (especially living in the COVID-19 era) were reusable syringes, which were part and parcel of many Soviet citizens’ medical kits. The most common method of disinfecting those syringes was boiling them. However, as far as we know, boiling doesn’t guarantee sterility, since many viruses are notable for being able to survive boiling temperatures, for example Hepatitis B or C (I believe, our level of medical knowledge has increased greatly over the last year).

Anyway, despite the lack of data regarding the cases of infection, the Soviet system of epidemic control proved to be extremely efficient in controlling and eradicating infectious diseases in areas of transmission. But there are still too many questions that have been left unanswered.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox