When a defecting Soviet spy named Georgy Agabekov unwarrantedly fled Turkey, where he had been placed by Soviet intelligence, to Paris, the Soviet secret police sentenced the defector to death in absentia. Behind the plot to kill the defector was Alexander Korotkov, a young intelligence officer, who only recently was a mere elevator technician at Lubyanka.

Alexander Korotkov was not initially destined to become a notorious spy. An offspring of a poor family, he had to abandon his dreams of studying at the Moscow State University in favor of working as a technician to help his mother who — in the absence of a spouse — overworked to stay afloat.

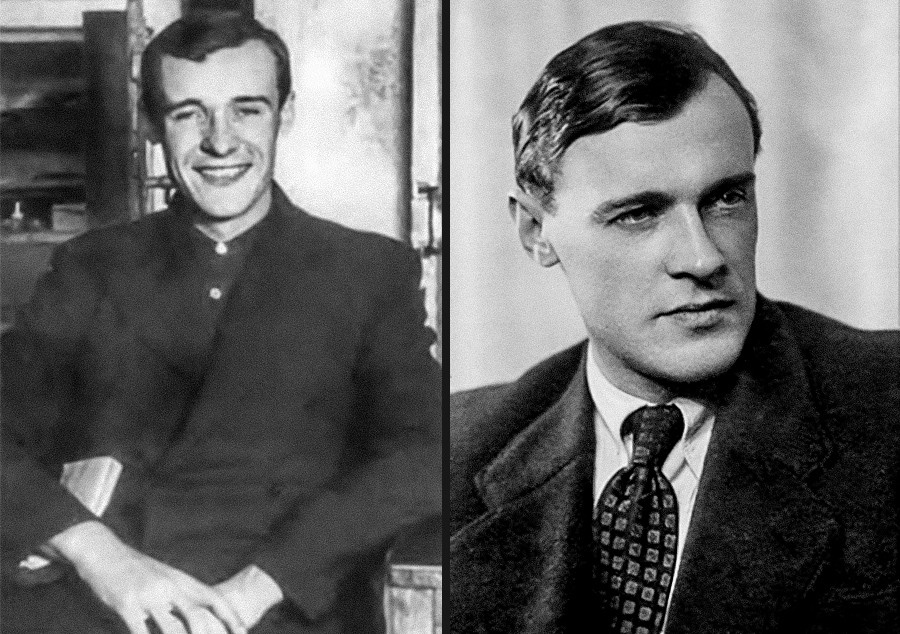

Young Alexander Korotkov.

Archive photoTennis was the young man’s escape from mundane life and it, as it happened, also drastically altered the course of his life that otherwise could have been as uneventful as that.

Korotkov played tennis at the Dinamo sports club and occasionally served as a ball boy during matches between other players. One of them was Veniamin Herson, an employee at the Joint State Political Directorate, the Soviet Union’s secret police aka OGPU.

“A person who wanted to join the Dinamo society had to work in the OGPU system. Otherwise, it was impossible to become a Dinamo player,” said writer and historian of Soviet intelligence services Theodore Gladkov.

Herson employed Korotkov as an elevator technician at Lubyanka, the headquarters of the secret police at the time.

Perhaps, Herson’s only intention was to help the young man to boost his sports career, but life seemed to have other plans. After working as a technician for only a few months, Korotkov advanced into the ranks of a clerk and, soon after, he became an assistant to an acting OGPU operative. It was then that Korotkov’s extraordinary career began.

Soon thereafter, Korotkov ended up in an intelligence directorate of the secret police.

Paying tribute to the exceptional qualities of the young spy, the intelligence bosses invested in Korotkov to make him a highly efficient — and lethal — intelligence asset of the Soviet Union, a country that dealt ruthlessly with its political enemies abroad.

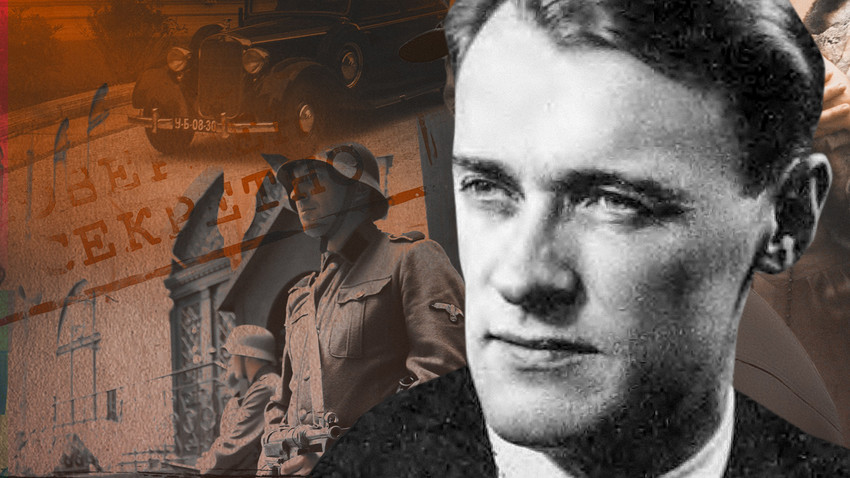

One of the first of Korotkov’s targets was Georgy Agabekov, a notorious Soviet spy who defected from the intelligence service and resorted to making money by publishing highly compromising materials about the Soviet intelligence.

One of the first of Korotkov’s targets was Georgy Agabekov (pictured), a notorious Soviet spy who defected from the intelligence service.

Archive photoBeing a former resident agent in Iran, Agabekov’s publications destabilized Soviet positions in the country and compromised a number of Soviet undercover intelligence agents who lost their lives as a result.

Upon receiving the order to kill the culprit, Korotkov devised a plot that intended to lure Agabekov to a secret meeting place in Paris by proposing a deal to smuggle gemstones allegedly stolen in Spain. The defector took the bait and soon ended up packed in a suitcase at the bottom of Seine.

Other political killings followed suit. Describing an episode where he allegedly decapitated one of Trotsky’s followers in a private letter to the head of the Soviet security apparatus Lavrenty Beria, Korotkov wrote that he “performed the most sinister, unpleasant, and dangerous work” while in the field.

Yet soon, Korotkov's talent for intelligence gathering and cultivating intelligence sources abroad prevailed over his other, more sinister knacks and he was dispatched to Nazi Germany on an undercover mission just before the war with the Soviet Union broke out.

Korotkov’s mission was to establish connections with sleeper agents in Nazi Germany and provide the Soviet Union with intelligence on the Nazi’s military research and development.

Soviet colonel Alexander Korotkov and German field marshal Wilhelm Keitel.

Archive photoA few months before the Nazi invasion of the USSR, Korotkov warned Moscow about the upcoming attack. “The mentioned source recently stated that the attack against the Soviet Union is a decided issue,” Korotkov’s note to Beria stated.

Although Korotkov’s message corroborated secret dispatches of other Soviet spies, Stalin is known to have ignored the alarming warnings.

When the war finally broke out, Korotkov found himself sealed in the Soviet embassy in Berlin, which was blocked and secured by members of the Schutzstaffel corps. Despite being seemingly immobilized, Korotkov miraculously managed to convince the head of the SS corps on guard to let him out for a brief period of time.

Under the pretext of meeting his girlfriend, Korotkov met a number of Soviet intelligence agents in Nazi Germany to pass them the money and equipment to continue their missions during wartime.

Soviet colonel Alexander Korotkov and general Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, who was one of the signatories to Germany's unconditional surrender at the end of the war.

Archive photoEven more surprisingly, Korotkov managed to escape Nazi Germany and reach Moscow, where he trained and prepared new Soviet intelligence agents to work behind the enemy lines.

After the war, Korotkov returned to occupied Germany. “He was one of the founders of East Germany’s intelligence. Suffice it to say that he had been in contact with such a person as Heinz Felfe, [a high-ranking spy based] in West Germany. This person is called the German Philby. He held very important positions in [West] German counterintelligence and was one of the most valuable sources for Soviet counterintelligence,” said writer Jan Edynak of Alexander Korotkov.

Alexander Korotkov in 1961.

Archive photoKorotkov remained involved in political and intelligence games up to his death on June 27, 1961. 51-year-old Korotkov, a major general at the time, died of an aorta rupture while playing tennis at the Dinamo club in Moscow. He went down in history as one of the most remarkable intelligence officers of the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox