Money, success...

Russia beyond (Photo: Vladimir Borovikovsky; Ivan Kramskoi; Public domain)When Nicholas II attended church services, he often made a donation to the church, just like the other parishioners – by putting a coin into a cup. Nicholas II used gold 5 ruble coins bearing his own portrait (5 ruble was a very generous donation – it could be a month’s pay for a maid, or half of a factory worker’s salary). Surprisingly, the Emperor didn’t have money at his own disposal.

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna with her daughters at a charity fair

Archive photoAs Russian historian Igor Zimin notes in his “Tsar’s Money: Income and expenses of the House of Romanovs,” to get these 5 ruble coins (just like any other amounts of cash), Nicholas II had to write short notes to the Empress’ Office – in the family of Nicholas II and Alexandra Fyodorvna, she took care of the finances. “Send me 3,000 rubles and two 5 ruble gold coins.” “Send me two more gold 5 rubles.” Didn’t the Emperor have unlimited access to the nation’s resources, including money? Actually, no.

Family of Paul I of Russia

Gerhard von KügelgenBefore Paul I (1754-1801), Russian tsars could really use the nation’s treasury as their purse. At least, nothing stopped them from doing so. Maybe that was one of the reasons Catherine II left a 200 million ruble national debt after she died (about three times the annual budget of the Russian Empire).

Paul, Catherine the Great’s son and heir, and his wife, Empress Maria Fyodorovna, had 10 children. Paul I foresaw that eventually, his offspring would be numerous, and they would all have to have some financial support from the Romanov House. Naturally, members of the Romanov House couldn’t work or do business themselves – their royal status didn’t allow them to do so. So an allowance from the state’s budget was necessary for the members of the family just to make a living. Moreover, a decent financial status of the members of the House was necessary to upkeep the Romanovs’ prestige among the European royalties.

Paul I understood that if he didn’t limit the use of the state’s reserves by the Romanov family, it would eventually grow so vast that it would drain the treasury. In 1797, Paul issued a decree that defined the annual allowances for the members of the family.

The building of the Ministry of the Imperial Court and Estates in St. Petersburg. Here, the Imperial Family's money was taken care of.

Archive photoPaul’s decree introduced a complicated hierarchical system of allowances for members of the royal family, depending on their respective relations to the throne. The allowance of the Emperor wasn’t defined. The Empress’s annual allowance was 600,000 rubles – a huge sum of money: an annual salary of a state minister at the time could be 4,000-5,000 rubles, and the Small Imperial Crown, created in 1801 for Empress Elizabeth Alekseevna (1779-1826), was estimated at more than 50,000 rubles.

Every child of a tsar received an annual 100,000 rubles allowance until their coming of age, which came at 20. After 20, their annual pay dropped to 50,000 rubles a year. The heir received 300,000 rubles, and his wife – 150,000 rubles, each of their children (i.e. the Emperor’s grandchildren) received 50,000 rubles until they reached the age of 20, and after that – 150 000 rubles annually, except that granddaughters of the Emperor could only have that pay until they married, after which the allowance stopped.

Alexander III of Russia with his family, 1886.

Public domainPaul’s decree contained many more conditions that foresaw the financial future of the Emperor’s offspring as far as five generations ahead (great-grandchildren). By the 1880s, the Imperial family had 23 members, they all used their allowances, and the family was about to grow, which meant a greater burden on the treasury. In 1885, Alexander III reduced the allowances of the Imperial family threefold – for example, the Empress’s annual allowance was cut to 200,000 rubles, the heir’s ‘salary’ was cut to 100,000 rubles from 300,000, the Emperor’s children (except the heir) were now allowed ‘only’ 33,000 rubles a year. Still, huge sums for the times when an officer's full dress uniform was 70 rubles, and 200 rubles bought you a piano.

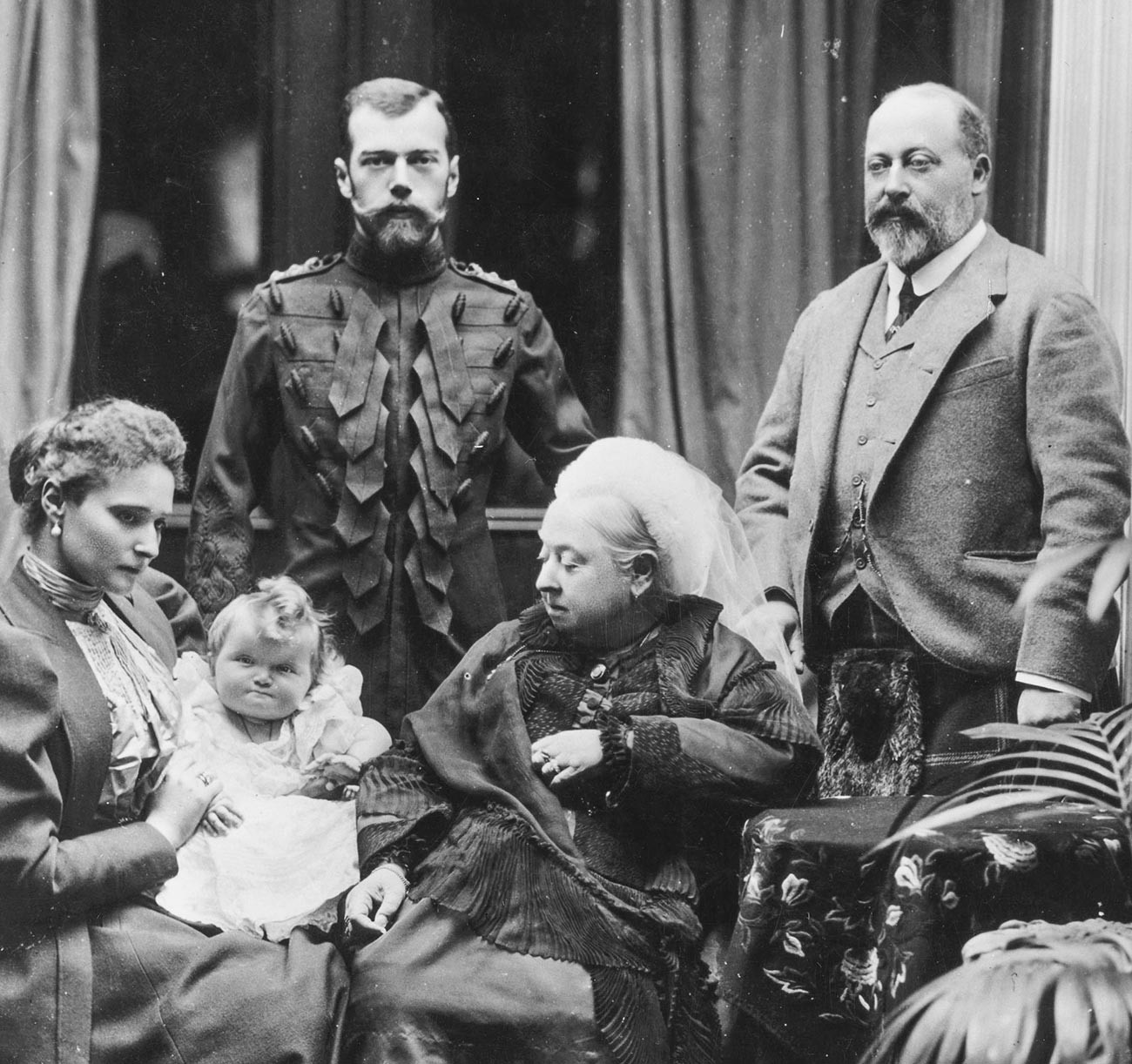

Queen Victoria and her son, Prince Edward VII (r), with Russian Emperor Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, and their newborn daughter, Olga.

Getty ImagesIn Russia, tsars and members of their family couldn’t go shopping – this would have demanded special security measures, the tsar would be instantly recognized by everybody, and the trip would instantly turn into a tsar’s meeting with the people.

So the Emperors, Grand Dukes and their families preferred to go shopping while on their trips to Europe, where they had a chance of being incognito. Nicholas II’s sister, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, wrote about her trip to Copenhagen: “I’ll never forget the excitement I felt when, for the first time in my life, I could just walk the street, stare into the shops’ windows, knowing that I could just go in any of them and buy anything I wanted!”

In 1909, Nicholas II himself did the same while he was abroad. As Anna Vyrubova, the Empress’s lady-in-waiting, remembered, Nicholas “took everything he wanted, not asking about the price – he didn’t have any understanding of the concept of money, because the State paid for everything.”

However, for the foreign owners of the shops Russian Emperors and their relatives visited, it was quite a hard task to get the money for the purchases – the bills were to be sent to the Empress’s Office, which controlled all the cash and purchases of the Imperial family. The Empress’s office approved the bills one more time with the persons who made the purchases, then the Ministry of Finance sent the money to the consulate of the country where the purchase was made, and only then, finally, the money was transferred to the seller. In the 19th century, this could take months.

Russian Chapel in Darmstadt

Eva KröcherWhat were the purchases Emperors made? Igor Zimin indicates some of them. Nicholas I (1796-1855) used to pick presents for his family himself – for his wife, he could buy hats (the Emperor didn’t choose the hats himself, he took with him an experienced lady-in-waiting, who knew the Empress’s taste), a bracelet, or even silk stockings.

But most of the Emperors’ and their relatives’ ‘own money’ usually went to charity. For example, in 1898 Nicholas II sent 500,000 rubles to charity – to help families that had suffered in the famine of that year. Also, in 1896-1900, Nicholas used over 500,000 rubles of his personal money to support the construction of the Russian Chapel in Darmstadt, the hometown of his wife Alexandra Fyodorovna.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox